Abstract

Early Islam, spanning its nascent centuries from the early 7th century, encompasses a pivotal epoch covering the life and teachings of the Prophet Muhammad, the establishment of Islamic principles, the codification of the Qur’ān, and the evolution of Islamic law and theological thought. This article outlines the findings of a pioneering bibliometric analysis of 764 high-value articles on early Islam from the Web of Science (WoS) database and unveils critical trends. This study, which notably highlights increased academic activities, particularly interdisciplinary expansion into archaeology and related fields, demonstrates a contemporary upsurge in scholarly engagement within humanities and social sciences. Global contributions from 60 countries, led by the USA, showcase an international landscape, and English emerges as the predominant language. (Der) Islam-Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur des Islamischen Orients and Journal of Archaeological Science Reports stand out as the most prolific journals across all fields, followed by Journal of Archaeological Science. This highlights the growing significance of archaeology in the research on early Islam. The top authors with the most publications N. Schibille, I. Taxel, and G. Bar-oz and most cited authors I. C. Freestone, J. Henderson, and Y. Avni shape the field. Financial support from organizations like the European Research Council (ERC), the Spanish Government and the Israel Science Foundation signals strategic investments in Islamic studies. Lastly, a keyword analysis emphasizes prevalent themes, such as Islam, early Islam, early Islamic period, and Qur’ān, providing a concise snapshot of the field’s contemporary focus. These insights underscore the rising international importance of Islamic research. Recognizing the limitations of the present study, this bibliometric analysis offers a foundational framework for future research by inspiring further scholarly exploration of emerging trends and thematic gaps in the field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The dissemination of Islam has profoundly influenced societies, cultures, and civilizations of human history since its advent, rendering early Islam an epoch with far-reaching historical significance. This transformative impact has spurred scholars and researchers to engage in extensive inquiries into Islamic literature over the last centuries (Hoyland 1997; Nigosian 2004; Hoyland 2012; Buskens and Van Sandwijk 2016; Salvatore et al. 2018). Notably, the term “early Islam” has emerged as a recurrent theme in scholarly discourse, garnering considerable attention and citations (Watt 1990; Berg 2017; Sahner 2023). In recent times, the academic fascination with this term has experienced a notable upsurge across a diverse range of disciplines (Johns 2003, Milwright 2010; Fuks et al. 2020; Srigyan et al. 2022; Fadel and Al-Hendy 2022). This article delves into the extensive body of research indexed by the Web of Science (WoS) to reveal consistent applications of the term “early Islam” in chronological categorization.

While the specific temporal boundaries of early Islam can vary depending on the topic under consideration, a prevailing trend in the current literature on this subject encompasses the first four centuries of Islam, spanning c.600-1000 AD. Several studies have delved into the periodization of Islamic history.Footnote 1 Despite widespread use of the term “early Islam”, however, there is a notable absence of comprehensive or bibliometric literature reviews and critical assessments of its historical evolution. Given the rising interest among researchers and institutions in early Islamic history, and the consequently expanding body of literature relating thereto, the present study is prompted by the need for a bibliometric analysis to address this scholarly void. By undertaking a meticulous examination of articles indexed in the Web of Science Core Collection database (maintained by Clarivate Analytics) between 2000 and 2022, this article offers a substantive contribution to existing knowledge on this topic. In this way, it aims to enhance understanding of the dynamics surrounding scholarship on early Islam.

Main purpose of this paper is to identify scholarly publications on early Islam and understand the broad intellectual structure of this body of research. It aims to offer a comprehensive bibliometric analysis of the term “early Islam”, as often used by modern scholars, but will neither determine the boundaries of the period defined as early Islam nor propose any periodization. Instead, the study will use this analysis to identify research fields (and gaps), leading authors, countries, fields of study, journals, and most cited articles centred on the term “early Islam” in the third millennium.

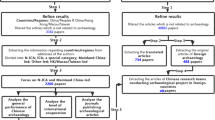

This study seeks to answer the research questions (RQs) found in Fig. 1. Each of these questions correlates to a respective subheading presented in the Results section:

This study is composed of three parts, as follows: Section 1 (Methodological analysis) details the research methodology and data; Section 2 (Results) presents and discusses the findings from the collected data; and Section 3 (Conclusion) concludes the study by offering some recommendations for future research.

Methodological analysis

This study mined the Web of Science (WoS) Core Collection database for documents on which to find its bibliometric analyses. The Web of Science (WoS) platform, by aggregating international scientific publications, serves as an ideal data source for such analyses, enabling comprehensive evaluations that span diverse research domains (Birkle et al. 2020).

The documents for this study were selected in accordance with the research process shown in Fig. 1. Before data collection, the topic search term “early Islam*” was first identified, being the most preferred term in contemporary Islamic history research. This term was then searched for in the title fields, abstracts and keywords of WoS articles on 24 June 2023. To prevent data variations, only the results of the search performed on this date were taken into account. The search was conducted in this way because some researchers use the term “early Islam” synonymously with the terms “early Islamic” and “early Islamicate.”Footnote 2 The first search with the term “early Islam*” yielded 1642 results. During the second stage, these results were further refined by restricting the document type to take only articles, review articles and early access articles into account. This process removed 760 studies classified as books, book reviews, proceeding papers, and editorial materials. Thus, 882 results remained. After further refining the temporal range to 2000–2022, 806 results remained. We have two reasons for making such a limitation. Firstly, there is not enough data for analysis before 2000 (76 records). Secondly, these studies are mostly inaccurately recorded in the WoS database. This data was then extracted, and a cleaning of individual results began. Cleaning was carried out in two stages: first, results included due to technical errors were eliminated; then, results that were irrelevant to the content analysis were removed. The first stage involved separating duplicates from document types that were incorrectly registered in WoS, as well as articles that were first published as early access articles and then later assigned to a completed journal. The second stage involved identifying results that were irrelevant because they did not consciously use the term “early Islam” in their titles, abstracts, or keywords (i.e., they did not in fact involve the early Islamic period). Moreover, studies that used the term “early Islam” to mean Islam’s geographical advent rather than the broader period spanning c.600 to c.1000 AD were also excluded from analysis. These sorting and screening procedures left 764 results remaining. These results were then analysed as this study’s data set (for the detailed process, see Table 1 and Fig. 2).

The collection of 764 articles identified as the final dataset was saved as a marked list within the WoS. To facilitate subsequent scientific mapping using the VOSviewer software program (Van Eck and Waltman 2023), this dataset was then extracted in a tab-delimited format, capturing both the complete record of information as well as the references cited therein. VOSviewer is a freely available bibliometric visualization tool acknowledged for its user-friendly interface and was deliberately selected due to its capacity to handle substantial datasets. This program provides an array of analytical and exploratory features, generating visual representations that aid the evaluative examination of data patterns (Van Eck and Waltman 2010). However, it identifies distinct clusters within the dataset, encompassing various aspects, such as authors, institutions, countries, and keywords. These clusters were represented visually using different colours, while the size of individual data nodes within the figures denoted the frequency or prevalence of a specific item—whether it be prolific authors, journals, institutions, countries, or frequently co-occurring keywords. The examination focused on two primary variables: first, we delved into co-authorship connections across researchers, organizations, and countries. Secondly, we explored patterns of author-provided keywords. In this context, the nodes within the visualizations represented authors, institutions, countries, and keywords. In the context of data visualization, Microsoft Excel 365 was employed for creating graphs, maps, and pie charts, while Microsoft Visio was utilized for generating flowcharts and relational tables.

Results

Analysis of publication time trend

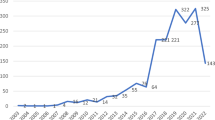

Figure 3 illustrates changes in the trend of annual publications on early Islam between 2000 and 2022. Although the general trend reflects a gradual rise in annual publications over the years, the increments of this increase have fluctuated rather than remained stable. Notably, of all 764 articles in the dataset, 348 (45.53%) were authored in the last five years. There are several potential reasons for this growth. The first is a remarkable increase in archaeological research (see Fig. 4). In addition, this notable rise could be the result of significant funding provided by supranational bodies, such as the European Research Council (ERC), and other national funders, like the Spanish Government and the Israel Science Foundation. Within this study’s timeframe, an especially noteworthy peak took place in 2021, when 93 articles were published—12.17% of the entire dataset over two decades. This growth in publications is anticipated to persist and to increase further.

Research areas

The research fields with a minimum of 15 or more publications on early Islam are Archaeology (n = 239, 31.28%), Religion (n = 163, 21.33%), Asian Studies (n = 121, 15.83%), History (n = 84, 10.99%), Arts Humanities-Other Topics (n = 71, 9.29%), Geology (n = 64, 8.37%), Anthropology (n = 57, 7.46%), Area Studies (n = 24, 3.14%), Business Economics (n = 19, 2.48%), Art (n = 16, 2.09%), and Chemistry (n = 16, 2.09%).

The data indicates that studies on early Islam in the last quarter of a century or so have seen archaeological enquiry dominate publication output. This is clearly due to excavations that are currently being carried out in the geography of early Islam.Footnote 4 The findings from these excavations are published in the form of excavation reports, in which the relevant region’s relationship with early Islam is also mentioned. Archaeological studies are also observed to have increased in the recent years. This seems to be due to the impact of research funding for archaeological excavations.

Countries

Researchers based in 60 different countries published research on early Islam between 2000 and 2022. However, researchers in some countries have contributed more to existing research than others. In terms of numbers of publications and citations on “early Islam”, Fig. 5 shows the countries and regions in which researchers have been most active. Figure 6 shows collaborative relations between countries regarding the early Islam studies included in the dataset. The USA provided the largest number of contributors to the field, having the highest number of publications (with 166; 21.728%). This was followed by the UK (with 119), Israel (with 114), Germany (with 66) and France (with 51). The USA ranks first in terms of number of publication contributions, WoS citations, citations per article, and total link strength, highlighting that its academic cohort has been quite dominant in the early Islam field. Some 670 articles were published in the ten most active countries. Of these top ten countries, one is in North America, five in Europe, three in the Middle East, and one in Asia. Archaeological studies are one of the factors enabling Israel to rank third.

Academic affiliation

In terms of publication numbers and total citation counts, Table 2 presents the top five institutions that have published research on early Islam, including their countries of origin. An analysis of these institutions, along with influential figures in the field, aids understanding and staying abreast of the latest developments and most authoritative perspectives in this area. Israel stands out as the country with the most contributing institutions with 114 articles between 2000 and 2022. Table 2 highlights the University of Haifa as the affiliate with the most publications (n = 48) on early Islam. The Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) is in second place with 38 publications, and the Israel Antiquities Authority is in third place with 35 publications. Israel stands out in this dataset with three institutions. The data reveals that the top five affiliates contribute over a quarter of the total literature output on early Islam, thus signifying a distribution of research on this topic across multiple academic establishments, rather than such work being concentrated predominantly within a select few (for a network of authors’ affiliations, see Fig. 7).

Research funding organizations

An analysis of the top ten institutions funding articles on early Islam between 2000 and 2022 offers valuable insight into the scholarly emphasis and support for research in this specific area (Table 3). The European Research Council (ERC) emerges as the foremost contributor, funding as many as 40 projects. This remarkable investment underscores the ERC’s commitment to advancing understandings of early Islam. The substantial number of ERC funded projects suggests a dedicated effort to unravel the complexities of the formative period of Islamic civilization. The Spanish Government’s allocation of resources to 28 projects reflects a considerable focus on research pertaining to early Islam, highlighting the importance of understanding the historical and cultural interactions between Islam and Spain, given the region’s rich history of Islamic influence. The funding supports studies that shed light on the impact that early Islam has had on Spanish society, architecture, language and intellectual heritage. Spain’s significant contribution underscores its dedication to unravelling the historical narratives and legacies of early Islamic civilization within its own context. The Israel Science Foundation’s support for 20 projects indicates a notable interest in interdisciplinary studies that examine the interactions between early Islam and other cultural and religious contexts. In summary, the top three funding institutions in the field of early Islam have collectively made significant contributions to advancing knowledge about this crucial period in Islamic history. Their investments underscore a multifaceted exploration of early Islamic civilization, spanning its impact on different regions, cultures, and intellectual traditions.

Authorship and co-authorship analysis

In total, 1185 different authors have written articles on early Islam. As shown in Table 4, N. Schibille and I. Taxel have been by far the most active contributors (n = 13; 1.702%). G. Bar-Oz and Y. Tepper are joint second (n = 12; 1.571%), and I. C. Freestone is third (n = 11; 1.440%). In addition, Freestone (492 citations), Henderson (291 citations) and Molera (214 citations) appear to be among the most influential authors on this topic in terms of citations. The authors with the highest number of articles on early Islam in the study’s dataset specialize in archaeology and archaeometry. Figure 8 represents co-authorships on early Islam of authors with at least one publication and one citation. It depicts co-authorship links between these authors over time.

Influential journals

The retrieved documents (n = 764) were published in a total of 310 journals from different fields of study. Table 5 shows the top ten journals (record count = n > 10) identified as sources of literature in this field from 2000 to 2022. These journals published a total of 182 documents, accounting for 23.79% of the entire literature. Each had at least ten publications on the topic, with the top positions going to (Der) Islam-Zeitschrift für Geschichte und Kultur des Islamischen Orients with 26 articles (3.4%), the Journal of Archaeological Science Reports with 26 articles (3.4%), and the Journal of Archaeological Science with 24 articles (3.14%). Half of the active journals in Table 5 were based in the UK. In addition, half were journals of archaeology. Among these, the Journal of Archaeological Science had the highest impact factor (5-year JIF = 3.0), followed by Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences (2.2) and Antiquity (2.0).

Language of publications

The diagram presented in Fig. 9 offers an overview of the linguistic distribution of published material concerning early Islam. In total, the analysed publications were written in 12 distinct languages. The data clearly indicates English to be the overwhelmingly dominant publication language for academic output on early Islam, constituting 683 (89.39%) of all papers. After this, Turkish occupies second position, contributing 23 (3.01%) of the documented works. This is followed by German (16, 2.09%); French (9, 1.17%), Russian (9, 1.17%) and Spanish (9, 1.17%); Arabic (6, 0.78%), Malay (3, 0.39%), Portuguese (3, 0.39%), Italian (2, 0.26%), and Croatian (1, 0.13%) and Slovenian (1, 0.13%). Thus, while scholarly articles have emerged from numerous countries worldwide, English unmistakably functions as the prevailing language for academic dissemination.

Citation analysis

Citation analysis of the dataset was conducted using VOSviewer. A citation analysis for authors was performed first, and followed by a citation analysis of the publications themselves to identify the most cited articles. Finally, a citation analysis was performed based on the journals in which these publications were published.

Figure 10 shows the relationship networks between authors with at least one publication and at least one citation. Of 764 publications, 525 were cited at least once, while 239 were not cited at all. The ten most cited articles and their authors are outlined in Table 6. Here, papers by I. C. Freestone et al. (2003), J. Henderson et al. (2004), and Y. Avni et al. (2006) have 100 or more citations. Figure 11 represents the citation networks between articles with at least five citations, highlighting the mutual citation relationships between authors. The citation relationships between journals with a minimum of 1 citation is shown in Fig. 12. Journals in the same or similar fields naturally appear to have a citation relationship with one another.

Keyword analysis

Analysing a particular scientific discipline, keywords assume significant importance by encapsulating the core content of articles. Examining patterns and trends in keyword compilations can shed light on specific academic research endeavours. Specific visualization techniques, like network maps and heat maps, can help to deepen understanding of the academic landscape on early Islam. The proportional frequency and link strength of terminology used in works on early Islam is depicted in Figs. 13 and 14. Islam, early Islam, early Islamic period, and Qur’ān are the most frequently used keywords. A closer analysis of these keywords sheds light on research trends and possible future research topics in the field. To this end, a keyword co-occurrence analysis was conducted using VOSviewer. As illustrated in Fig. 15, by setting a minimum occurrence threshold of 5 mentions per word, a total of 58 keywords emerged and were grouped into seven clusters. Figure 15 displays the distribution of these keywords, highlighting the prominence of certain terms such as “Islam” with 49 occurrences, followed by “early Islam” with 31 occurrences, “early Islamic period” with 30 occurrences, and “early Islamic” with 24 occurrences.

Cluster 1 is represented in red in the visualization and identifies one cluster of concepts with frequent inter-related occurrence. It has 13 keywords that stand out: Islam, early Islamic history, historiography, history, hadith, Muhammad, Palestine, Sufism, archaeology, and some of the related regions. Cluster 2 is green and includes topics related to early Islam, the Qur’ān, Late Antiquity, Zoroastrianism, asceticism, conversion, law, monasticism, Arabic, Pahlavi literature, and the Persian Gulf. Cluster 3 is blue and contains keywords more related to archaeology. These are early Islamic period, Islamic glass, Byzantine glass, Byzantine period, Jerash, Jordan, IA-ICP-MS, pottery, and Sasanian. Cluster 4 is yellow represents a set of keywords where the sub-disciplines of archaeology stand out. Here, related keywords are early Islamic, archaeobotany, zooarchaeology, Islamic archaeology, agriculture, Abbasid, trade, Jerusalem, and Israel. Cluster 5 is purple and is another archaeology-focused grouping more clearly dominated by Islamic and Byzantine glass. Here, prominent keywords here are Islamic, Byzantine, Roman, Umayyad, shipwreck, glass, mosque, and technology. Group 6 is light blue and clustered with the keywords of Islamic history, Prophet Muhammad, Iran, Central Asia. Cluster 7 is orange and contains such topics as the Qur’ān, religion, and ethics.

Conclusion

This study highlights several critical outcomes based on the bibliometric analysis of publications related to early Islam from the WoS database. It reveals the growing prominence of archaeology in early Islamic studies, reflecting a shift toward interdisciplinary approaches that integrate archaeological findings with traditional historical and religious scholarship. Another key outcome is the broad adoption of the term “early Islam” which enables a more inclusive examination of the period and facilitates the exploration of diverse aspects and socio-political contexts beyond traditional periodizations.

This study has several limitations. First, data prior to 2000 is excluded due to higher error rates and fewer records, which affect the accuracy and reliability of the analysis. The focus on data from 2000–2022 ensures greater precision and robustness. Second, the WoS database limits the study, as it does not include articles from local journals in Arabic, Turkish, Persian, Malay, and Urdu. While the WoS database is comprehensive, including the Arabic Citation Index (ARCI) in the future may address this gap and improve bibliometric analyses of early Islamic studies.

Finally, another bibliometric analysis could be conducted on leading journals from the dataset, which publish research on early Islam. Such analysis could assess the impact and status of these journals in the academic community and provide more precise insights into the field’s dynamics and trends.

Data availability

The data for this study’s conclusions were acquired from databases in the public ___domain of the Web of Science Core Collection, and the key term “early Islam*” can be used in data extraction searches. The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study, nevertheless, are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

One of the paramount figures in the periodization of Islamic history is Marshall G. S. Hodgson (1922–1968), an eminent American historian and orientalist. His monumental work of three volumes and six books offers groundbreaking perspectives that challenged traditional periodization in Islamic history. His initial two books of the first volume, titled “The Islamic Infusion: Genesis of a New Social Order (625–692)” and “The Classical Civilization of the High Caliphate (692–945)”, provided a groundbreaking re-evaluation of the years 625–945, challenging conventional political periodization with a multi-layered perspective (see Hodgson 1974). For other studies addressing the issue of periodization in Islamic history, see Goitein (1968); Burke (1979); Morony (1981); Khalidi (1998); Al-Azmeh (1998); Hirschler and Savant (2014); Donner (2014); Bashir (2014); Demirci (2016); Harputlu (2016); Zekkar (2016).

For the emergence of term of “Islamicate”, see Hodgson, 1979. Also, for a new perspective on the term of ‘Islamic History’ from a recent study, see Sahner (2023).

Using the asterisk (*) function, our intention is to examine not only the concept of “early Islam” but also related terms such as “early Islamic” and “early Islamicate” in a comprehensive manner.

For an in-depth examination of archaeological excavations and research conducted within regions historically inhabited by Muslim populations, see Walker et al. (2020).

References

Al-Azmeh A (1998) Muslim history: reflections on periodisation and categorisation. Mediev Hist J 1(2):195–231. https://doi.org/10.1177/097194589800100202

Avni Y, Porat N, Plakht J, Avni G (2006) Geomorphic changes leading to natural desertification versus anthropogenic land conservation in an Arid environment, the Negev Highlands, Israel. Geomorphology 82(3-4):177–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geomorph.2006.05.002

Bashir S (2014) On Islamic time: rethinking chronology in the historiography of Muslim societies. Hist Theory 53(4):519–544. https://doi.org/10.1111/hith.10729

Berg H (ed.) (2017) Routledge handbook on early Islam. Routledge, London

Birkle C, Pendlebury DA, Schnell J, Adams J (2020) Web of Science as a data source for research on scientific and scholarly activity. Quan Sci Stud 1(1):363–376. https://doi.org/10.1162/qss_a_00018

Burke E (1979) Islamic history as world history: Marshall Hodgson, ‘The Venture of Islam. Int J Middle East Stud 10(2):241–264. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0020743800034796

Buskens L, Van Sandwijk A (2016) Islamic studies in the twenty-first century: transformations and continuities. Amsterdam. Amsterdam University Press

De Blois F (2002) Nasrani (Nazoraios) and Hanif (Ethnikos): studies on the religious vocabulary of Christianity and of Islam. Bull Sch Orient Afr Stud 65:1–30

Demirci M (2016) İslam tarihinin dönemlendirilmesi problemi. Fırat Üniversitesi Orta Doğu Araştırmaları Dergisi 11(1):3–44

Donner FM (2014) Periodization as a tool of the historian with special reference to Islamic history. Der Islam 91(1):20–36. https://doi.org/10.1515/islam-2014-0003

Fadel HE, Al-Hendy A (2022) Development of obstetric practice during the early Islamic Era. Reprod Sci 29:2587–2592. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43032-022-00887-1

Freestone IC, Jackson-Tal RE, Tal O (2008) Raw glass and the production of glass vessels at Late Byzantine Apollonia-Arsuf, Israel. J. Glass Stud 50:67–80

Freestone IC, Leslie KA, Thirlwall M, Gorin‐Rosen Y (2003) Strontium isotopes in the investigation of early glass production: Byzantine and early Islamic glass from the Near East. Archaeometry 45(1):19–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-4754.00094

Fuks D, Amichay O, Weiss E (2020) Innovation or preservation? Abbasid aubergines, archaeobotany, and the Islamic Green Revolution. Archaeol Anthropol Sci 12:50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12520-019-00959-5

Goitein SD (1968) A plea for the periodization of Islamic history. J Am Orient Soc 88(2):224–228. https://doi.org/10.2307/597197

Harputlu Ş (2016) Tarih sorunları: İslam tarihinin periyotlara ayrılması. Fırat Üniversitesi Orta Doğu Araştırmaları. Dergisi 11(1):61–71

Henderson J (2002) Tradition and experiment in first millennium AD glass production the emergence of early Islamic glass technology in Late Antiquity. Acc Chem Res 35(8):594–602. https://doi.org/10.1021/ar0002020

Henderson J, McLoughlin SD, McPhail DS (2004) Radical changes in Islamic glass technology: evidence for conservatism and experimentation with new glass recipes from early and middle Islamic Raqqa, Syria. Archaeometry 46(3):439–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2004.00167.x

Hirschler K, Savant SB (2014) Introduction–what is in a period? Arabic historiography and periodization. Der Islam 91(1):6–19. https://doi.org/10.1515/islam-2014-0002

Hodgson MGS (1974) The venture of Islam: conscience and history in a world civilization. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Hoyland RG (1997) Seeing Islam as others saw it: a survey and evaluation of Christian Jewish and Zoroastrian writings on early Islam. The Darwin Press Inc, Princeton, New Jersey

Hoyland RG (2012) Early Islam as a Late Antique Religion. In: Johnson SF (ed) The Oxford Handbook of Late Antiquity. Oxford University Press, Oxford, 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195336931.013.0032

Johns J (2003) Archaeology and the history of early Islam: the first seventy years. J Econ Soc Hist Orient 46(4):411–436. https://doi.org/10.1163/156852003772914848

Khalidi T (1998) Reflections on periodisation in Arabic historiography. Mediev Hist J 1(1):107–124. https://doi.org/10.1177/097194589800100107

Milwright M (2010) Introduction to Islamic archaeology. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Mirti P, Pace M, Ponzi MMN, Aceto M (2008) ICP-MS analysis of glass fragments of Parthian and Sasanian epoch from Seleucia and Veh Ardašīr (central Iraq). Archaeometry 50(3):429–450. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4754.2007.00344.x

Molera J, Vendrell-Saz M, Pérez-Arantegui J (2001) Chemical and textural characterization of tin glazes in Islamic ceramics from Eastern Spain. J Archaeol Sci 28(3):331–340. https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2000.0606

Morony MG (1981) Bayn al-Fitnatayn: problems in the periodization of early Islamic history. J Near East Stud 40(3):247–251. https://doi.org/10.1086/372894

Nigosian SA (2004) Islam: Its history, teaching, and practices. Indiana University Press, Bloomington, https://doi.org/10.1108/IMEFM-06-2020-0277

Phelps M, Freestone IC, Gorin-Rosen Y, Gratuze B (2016) Natron glass production and supply in the Late Antique and early medieval Near East: the effect of the Byzantine-Islamic transition. J Archaeol Sci 75:57–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2016.08.006

Salvatore A, Tottoli R, Rahimi B (eds.) (2018) The Wiley Blackwell history of Islam. Wiley Blackwell, 2018., Hoboken

Sahner CC (2023) What is Islamic history? Muslims, non-Muslims and the history of everyone else. Engl Hist Rev 138(592):379–409. https://doi.org/10.1093/ehr/cead129

Scheidel W (2010) Real wages in early economies: evidence for living standards from 1800 BCE to 1300 CE. J Econ Soc Hist Orient 53(3):425–462. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1114424

Siddall R (2018) Mineral pigments in archaeology: their analysis and the range of available materials. Minerals 8(5):201. https://doi.org/10.3390/min8050201

Srigyan M, Bolívar H, Ureña I et al. (2022) Bioarchaeological evidence of one of the earliest Islamic burials in the Levant. Commun Biol 5:554. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42003-022-03508-4

Stone EC (2008) Patterns of looting in Southern Iraq. Antiquity 82(315):125–138. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00096496

Van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2010) Software survey: VOS viewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics 84(2):523–538. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3

Van Eck NJ, Waltman L (2023) Manual for VOSviewer version 1.6.19. Universiteit Leiden, Leiden

Walker B, Insoll T, Fenwick C (eds.) (2020) The Oxford handbook of Islamic archaeology. Oxford University Press, New York

Watt WM (1990) Early Islam. Edinburgh University Press, Edinburgh

Zekkar S (2016) İslam tarihi yazımı-uygulama ve periyodizasyon. Fırat Üniversitesi Orta Doğu Araştırmaları. Dergisi 11(1):45–60

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All the authors contributed equally to completing the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval was not required as the study did not involve human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed consent

The authors declare that they did not involve human participants in the study, and therefore it was not necessary to obtain any consent about this kind of data.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yılmaz, H.İ., İzgi, M.C., Erbay, E.E. et al. Studying early Islam in the third millennium: a bibliometric analysis. Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1521 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04058-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04058-2