AI Is Blurring the Definition of Artist

By Ahmed Elgammal

Advanced algorithms are using machine learning to create art autonomously.

Advanced algorithms are using machine learning to create art autonomously.

With artificial intelligence (AI) becoming incorporated into more aspects of our daily lives, from writing to driving, it’s only natural that artists would also start to experiment with it.

Indeed, Christie’s recently sold its first piece of auctioned AI art—a blurred face titled “Portrait of Edmond Belamy”—for $432,500.

The piece sold at Christie’s is part of a new wave of AI art created via machine learning. Paris-based artists Hugo Caselles-Dupré, Pierre Fautrel, and Gauthier Vernier fed thousands of portraits into an algorithm, “teaching” it the aesthetics of past examples of portraiture. The algorithm then created “Portrait of Edmond Belamy.”

The painting is “not the product of a human mind,” Christie’s noted in its preview. “It was created by artificial intelligence, an algorithm defined by [an] algebraic formula.”

Images courtesy of the author.

If artificial intelligence is used to create images, can the final product really be thought of as art? Should there be a threshold of influence over the final product that an artist needs to wield?

As the director of the Art and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory at Rutgers University, I’ve been wrestling with these questions—specifically, the point at which the artist should cede credit to the machine.

During the past 50 years, several artists have written computer programs to generate art—what I call algorithmic art. The process requires the artist to write detailed code with a desired visual outcome in mind.

One the earliest practitioners of this form is artist Harold Cohen, who wrote the program AARON in 1973 to produce drawings that followed a set of rules he had created. Cohen continued to develop and refine AARON for the rest of his career, but the program maintained its core design of performing tasks as directed by the artist. New developments incorporate AI and machine learning technologies to allow the computer more autonomy in producing images.

To create AI art, artists write algorithms not to follow a set of rules, but to “learn” a specific aesthetic by analyzing thousands of images. The algorithm then tries to generate new images in adherence to the aesthetics it has learned.

To begin, the artist chooses a collection of images to feed the algorithm, a step I call pre-curation.

Most of the AI artworks that have emerged over the past few years have used a class of algorithms called generative adversarial networks (GANs). First introduced by computer scientist Ian Goodfellow in 2014, these algorithms are called “adversarial” because there are two sides to them: One generates random images; the other has been taught, via the input, how to judge these images and deem which best align with the input.

For example, an artist could feed portraits from the past 500 years into a generative AI algorithm. The algorithms then tries to imitate these inputs, producing a range of output images. The artist must sift through the output images and select those he or she wishes to use, a step I call post-curation.

Throughout this process, the artist maintains an active hand: He or she is very involved in pre- and post-curation, and might also tweak the algorithm as needed to generate the desired outputs.

The generative algorithm can produce images that surprise even the artist presiding over the process. For example, a GAN being fed portraits could end up producing a series of deformed faces. What should we make of this?

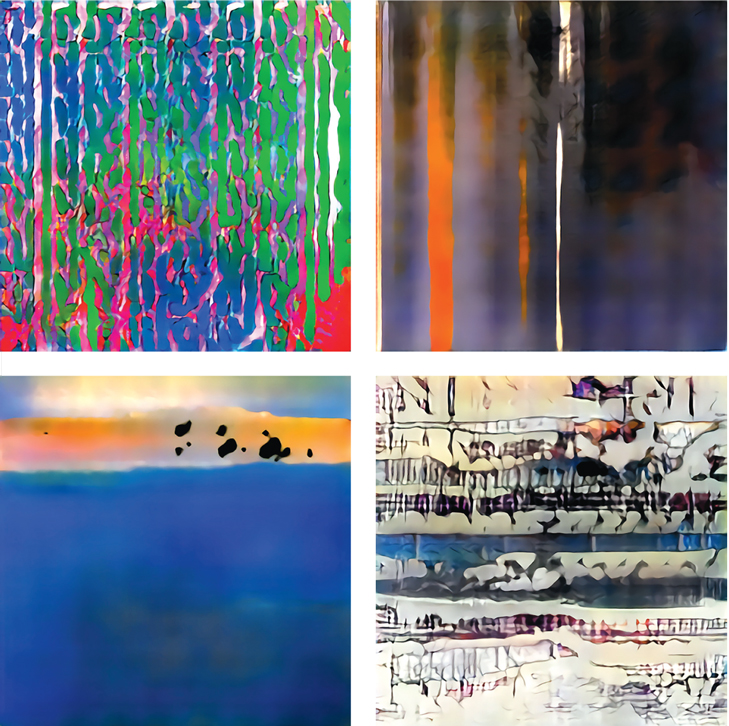

Images courtesy of Ahmed Elgammal.

Psychologist Daniel E. Berlyne has studied the psychology of aesthetics for several decades. He found that novelty, surprise, complexity, ambiguity, and eccentricity tend to be the most powerful stimuli in works of art.

The generated portraits from the GAN—with all of the deformed faces—are certainly novel, surprising, and eccentric. They also evoke British figurative painter Francis Bacon’s famous deformed portraits, such as “Three Studies for a Portrait of Henrietta Moraes.” But there’s something missing in the deformed, machine-made faces: intent.

Although it was Bacon’s intent to make his faces deformed, the deformed faces we see in the example of AI art aren’t necessarily the goal of the artist or the machine. What we are looking at are instances in which the machine has failed to properly imitate a human face, and has instead spat out some surprising deformities.

Yet this is exactly the sort of image that Christie’s auctioned.

I would argue that the deformed faces do not indicate a lack of intent because the intent lies in the process, even if it doesn’t appear in the final image.

For example, to create her artwork titled “The Fall of the House of Usher,” artist Anna Ridler took stills from a 1929 film version of the Edgar Allan Poe short story of the same name. She made ink drawings from the still frames and fed them into a generative model, which produced a series of new images that she then arranged into a short film.

Another example is Mario Klingemann’s “The Butcher’s Son,” a nude portrait that was generated by feeding the algorithm images of stick figures and images of pornography.

If artificial intelligence is used to create images,can the final product really be thought of as art?

I use these two examples to show how artists can play with these AI tools in any number of ways. Although the final images might have surprised the artists, they didn’t come out of nowhere: There was a process behind them, and there was certainly an element of intent.

Nonetheless, many are skeptical of AI art. Pulitzer Prize–winning art critic Jerry Saltz has said he finds the art produced by AI artists boring and dull, including “The Butcher’s Son.”

Perhaps critics are correct in some cases. In the deformed portraits, for example, you could argue that the resulting images aren’t all that interesting: They’re really just imitations—with a twist—of pre-curated inputs.

But it’s not just about the final image. It’s about the creative process—one that involves an artist and a machine collaborating to explore new visual forms in revolutionary ways.

For this reason, I have no doubt that AI-produced pieces are conceptual art, a form that dates back to the 1960s, in which the idea behind the work and the process is more important than the outcome.

As for “The Butcher’s Son,” one of the pieces Saltz derided as boring? It recently won the Lumen Prize, a prize dedicated to art created with technology.

When artificial intelligence has been used to create works of art, a human artist has always exerted a significant element of control over the creative process. But what if a machine were programmed to create art on its own, with little to no human involvement? Our lab has created AICAN (artificial intelligence creative adversarial network), a program that could be thought of as a nearly autonomous artist that has learned existing styles and aesthetics and can generate innovate images of its own.

People genuinely like AICAN’s work, and can’t distinguish it from that of human artists. Its pieces have been exhibited worldwide, and one even recently sold for $16,000 at an auction.

When designing AICAN, we adhered to a theory proposed by psychologist Colin Martindale. He hypothesized that many artists will seek to make their works appealing by rejecting existing forms, subjects, and styles that the public has become accustomed to. Artists seem to intuitively understand that they’re more likely to arouse viewers and capture their attention by doing something new.

Seventy-five percent of the time,viewers thought the algorithm generated images had been produced by a human artist.

In other words, novelty reigns.

When programming AICAN, we used an algorithm called the creative adversarial network, which compels AICAN to contend with two opposing forces. On one end, it tries to learn the aesthetics of existing works of art. On the other, it will be penalized if, when creating a work of its own, it too closely emulates an established style.

At the same time, AICAN adheres to what Martindale calls the “least effort” principle, in which he argues that too much novelty will turn off viewers. This careful combination ensures that the art generated will be novel but won’t depart too far from what’s considered acceptable. Ideally, it will create something new that builds off what already exists.

As for our role, we don’t select specific images to “teach” AICAN a certain aesthetic or style, as many artists who create AI art will do. Instead, we fed the algorithm 80,000 images that represent the Western art canon over the previous five centuries. It’s somewhat like an artist taking an art history survey course, with no particular focus on a style or genre.

At the click of a button, the machine creates an image that can then be printed. The works will often surprise us in their range, sophistication, and variation.

In prior work, my colleagues and I developed an algorithm that assessed the creativity of any given painting, while taking into account the painting’s context within the scope of art history (see sidebar, below). AICAN can use this work to judge the creativity of its individual pieces.

Because AICAN has also learned the titles used by artists and art historians in the past, the algorithm can even name the works it generates. It named one “Orgy”; it called another “The Beach at Pourville.”

The algorithm favors generating more abstract works than figurative ones. Our research on how the machine is able to understand the evolution of art history could offer an explanation (see the sidebar at the bottom of this article). Because it’s tasked with creating something new, AICAN is likely building off more recent trends in art history, such as abstract art, which came into vogue in the 20th century.

There was still the question of how people would respond to AICAN’s work. To test this reaction, we showed people AICAN images and works created by human artists that were showcased at Art Basel, an annual fair that features cutting-edge contemporary art. For each artwork, we asked the participants whether they thought it was made by a machine or an artist.

We found that people couldn’t tell the difference: Seventy-five percent of the time, they thought the AICAN-generated images had been produced by a human artist.

They didn’t simply have a tough time distinguishing between the two. They genuinely enjoyed the computer- generated art, using words such as “having visual structure,” “inspiring” and “communicative” when describing AICAN’s work.

Beginning in October 2017, we started exhibiting AICAN’s work at venues in Frankfurt, Los Angeles, New York City, and San Francisco, with a different set of images for each show.

At the exhibitions, we heard one question, time and again: Who’s the artist?

As a scientist, I created the algorithm, but I have no control over what the machine will generate. The machine chooses the style, the subject, the composition, the colors, and the texture. Yes, I set the framework, but the algorithm is fully at the helm when it comes to the elements and the principles of the art it generates.

For this reason, in the all exhibitions where the art was shown, I gave credit solely to AICAN for each artwork. At Miami’s Art Basel in December 2018, eight pieces, also credited to AICAN, were shown.

Image courtesy of the author.

The first artwork offered for sale from the AICAN collection, which AICAN titled “St. George Killing the Dragon,” was the one that sold for $16,000 at an auction in New York in November 2017. (Most of the proceeds went to fund research at Rutgers and the Institut des Hautes Etudes Scientifiques in France.)

Still, there’s something missing in AICAN’s artistic process: The algorithm might create appealing images, but it lives in an isolated creative space that lacks social context. Human artists, on the other hand, are inspired by people, places, and politics. They create art to tell stories and make sense of the world.

AICAN can, however, generate artwork that human curators can then ground in our society and connect to what’s happening around us. That’s just what we did with “Alternative Facts: The Multi Faces of Untruth,” a title we gave to a series of portraits generated by AICAN that struck us with its timely serendipity.

Of course, just because machines can almost autonomously produce art, it doesn’t mean they will replace artists. It simply means that artists will have an additional creative tool at their disposal, one they could even collaborate with.

I often compare AI art to photography. When photography was first invented in the early 19th century, it wasn’t considered art—after all, a machine was doing much of the work. The tastemakers resisted, but eventually relented: A century later, photography became an established fine art genre. Today, photographs are exhibited in museums and auctioned off at astronomical prices.

I have no doubt that art produced by artificial intelligence will go down the same path.

This article is adapted and expanded from The Conversation and Medium:

Click "American Scientist" to access home page

American Scientist Comments and Discussion

To discuss our articles or comment on them, please share them and tag American Scientist on social media platforms. Here are links to our profiles on Twitter, Facebook, and LinkedIn.

If we re-share your post, we will moderate comments/discussion following our comments policy.