An essay on substack; interpreting US inflation history via fiscal theory, prepared as comments for a session at the AEA meetings.

Thursday, January 4, 2024

Friday, December 8, 2023

New-Keynesian models, a puzzle of scientific sociology

This post is from a set of comments I gave at the NBER Asset Pricing conference in early November at Stanford. Conference agenda here. My full slides here. There was video, but sadly I took too long to write this post and the NBER took down the conference video.

I was asked to comment on "Downward Nominal Rigidities and Bond Premia" by François Gourio and Phuong Ngo. It's a very nice clean paper, so all I could think to do as discussant is praise it, then move on to bigger issues. These are really comments about whole literatures, not about one paper. One can admire the play but complain about the game.

The paper implements a version of Bob Lucas' 1973 "International evidence" observation. Prices are less sticky in high inflation countries. The Phillips curve more vertical. Output is less affected by inflation. The Calvo fairy visits every night in Argentina. To Lucas, high inflation comes with variable inflation, so people understand that price changes are mostly aggregate not relative prices, and ignore them. Gourio and Ngo use a new-Keynesian model with downwardly sticky prices and wages to express the idea. When inflation is low, we're more often in the more-sticky regime. They use this idea in a model of bond risk premia. Times of low inflation lead to more correlation of inflation and output, and so a different correlation of nominal bond returns with the discount factor, and a different term premium.

I made two points, first about bond premiums and second about new-Keynesian models. Only the latter for this post.

This paper, like hundreds before it, adds a few ingredients on top of a standard textbook new-Keynesian model. But that textbook model has deep structural problems. There are known ways to fix the problems. Yet we continually build on the standard model, rather than incorporate known ways or find new ways to fix its underlying problems.

Problem 1: The sign is "wrong" or at least unconventional.

Monday, December 4, 2023

FTPL news: discount and Economist list

Just in time for the holidays, the perfect stocking stuffer -- if you have really big stockings. 30% discount on Fiscal Theory of the Price Level until June 30 2024.

And Fiscal Theory makes the Economist's list of best books for 2023.

Thursday, November 16, 2023

FTPL at SEA

Sunday Nov 19 6-7 PM I will be giving the "Association Lecture" at the Southern Economics Association conference in New Orleans. The topic naturally is "The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level." If you're curious, and will be at the conference, stop by. I now have a pretty good condensed talk about fiscal theory!

Friday, October 13, 2023

Heterogeneous Agent Fiscal Theory

Today, I'll add an entry to my occasional reviews of interesting academic papers. The paper: "Price Level and Inflation Dynamics in Heterogeneous Agent Economies," by Greg Kaplan, Georgios Nikolakoudis and Gianluca Violante.

One of the many reasons I am excited about this paper is that it unites fiscal theory of the price level with heterogeneous agent economics. And it shows how heterogeneity matters. There has been a lot of work on "heterogeneous agent new-Keynesian" models (HANK). This paper inaugurates heterogeneous agent fiscal theory models. Let's call them HAFT.

Monday, August 28, 2023

Interest rates and inflation part 3: Theory

This post takes up from two previous posts (part 1; part 2), asking just what do we (we economists) really know about how interest rates affect inflation. Today, what does contemporary economic theory say?

As you may recall, the standard story says that the Fed raises interest rates; inflation (and expected inflation) don't immediately jump up, so real interest rates rise; with some lag, higher real interest rates push down employment and output (IS); with some more lag, the softer economy leads to lower prices and wages (Phillips curve). So higher interest rates lower future inflation, albeit with "long and variable lags."

Higher interest rates -> (lag) lower output, employment -> (lag) lower inflation.

In part 1, we saw that it's not easy to see that story in the data. In part 2, we saw that half a century of formal empirical work also leaves that conclusion on very shaky ground.

As they say at the University of Chicago, "Well, so much for the real world, how does it work in theory?" That is an important question. We never really believe things we don't have a theory for, and for good reason. So, today, let's look at what modern theory has to say about this question. And they are not unrelated questions. Theory has been trying to replicate this story for decades.

The answer: Modern (anything post 1972) theory really does not support this idea. The standard new-Keynesian model does not produce anything like the standard story. Models that modify that simple model to achieve something like result of the standard story do so with a long list of complex ingredients. The new ingredients are not just sufficient, they are (apparently) necessary to produce the desired dynamic pattern. Even these models do not implement the verbal logic above. If the pattern that high interest rates lower inflation over a few years is true, it is by a completely different mechanism than the story tells.

I conclude that we don't have a simple economic model that produces the standard belief. ("Simple" and "economic" are important qualifiers.)

The simple new-Keynesian model

Thursday, August 10, 2023

Interest rates and inflation part 2: Losing faith in VARs

(This post continues part 1 which just looked at the data. Part 3 on theory is here)

When the Fed raises interest rates, how does inflation respond? Are there "long and variable lags" to inflation and output?

There is a standard story: The Fed raises interest rates; inflation is sticky so real interest rates (interest rate - inflation) rise; higher real interest rates lower output and employment; the softer economy pushes inflation down. Each of these is a lagged effect. But despite 40 years of effort, theory struggles to substantiate that story (next post), it's had to see in the data (last post), and the empirical work is ephemeral -- this post.

The vector autoregression and related local projection are today the standard empirical tools to address how monetary policy affects the economy, and have been since Chris Sims' great work in the 1970s. (See Larry Christiano's review.)

I am losing faith in the method and results. We need to find new ways to learn about the effects of monetary policy. This post expands on some thoughts on this topic in "Expectations and the Neutrality of Interest Rates," several of my papers from the 1990s* and excellent recent reviews from Valerie Ramey and Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, who eloquently summarize the hard identification and computation troubles of contemporary empirical work.

Maybe popular wisdom is right, and economics just has to catch up. Perhaps we will. But a popular belief that does not have solid scientific theory and empirical backing, despite a 40 year effort for models and data that will provide the desired answer, must be a bit less trustworthy than one that does have such foundations. Practical people should consider that the Fed may be less powerful than traditionally thought, and that its interest rate policy has different effects than commonly thought. Whether and under what conditions high interest rates lower inflation, whether they do so with long and variable but nonetheless predictable and exploitable lags, is much less certain than you think.

Monday, August 7, 2023

Blinder, supply shocks, and nominal anchors

An a recent WSJ oped (which I will post here when 30 days have passed), I criticized the "supply shock" theory of our current inflation. Alan Blinder responds in WSJ letters

First, Mr. Cochrane claims, the supply-shock theory is about relative prices (that’s true), and that a rise in some relative price (e.g., energy) “can’t make the price of everything go up.” This is an old argument that monetarists started making a half-century ago, when the energy and food shocks struck. It has been debunked early and often. All that needs to happen is that when energy-related prices rise, many other prices, being sticky downward, don’t fall. That is what happened in the 1970s, 1980s and 2020s.

Second, Mr. Cochrane claims, the supply-shock theory “predicts that the price level, not the inflation rate, will return to where it came from—that any inflation should be followed by a period of deflation.” No. Not unless the prices of the goods afflicted by supply shocks return to the status quo ante and persistent inflation doesn’t creep into other prices. Neither has happened in this episode.

When economists disagree about fairly basic propositions, there must be an unstated assumption about which they disagree. If we figure out what it is, we can think more productively about who is right.

I think the answer here is simple: To Blinder there is no "nominal anchor." In my analysis, there is. This is a question about which one can honorably disagree. (WSJ opeds have a hard word limit, so I did not have room for nuance on this issue.)

Saturday, August 5, 2023

Interest rates and inflation -- part 1

Today I begin a three part series exploring interest rates and inflation. (Part 2 empirical work, Part 3 theory)

How does the Fed influence inflation? Is the recent easing of inflation due to Fed policy, or happening on its own? To what extent should we look just to the Fed to bring inflation under control going forward?

The standard story: The Fed raises the interest rate. Inflation is somewhat sticky. (Inflation is sticky. This is important later.) Thus the real interest rate also rises. The higher real interest rate softens the economy. And a softer economy slowly lowers inflation. The effect happens with "long and variables lags," so a higher interest rate today lowers inflation only a year or so from now.

interest rate -> (lag) softer economy -> (lag) inflation declines

This is a natural heir to the view Milton Friedman propounded in his 1968 AEA presidential address, updated with interest rates in place of money growth. A good recent example is Christina and David Romer's paper underlying her AEA presidential address, which concludes of current events that as a result of the Fed's recent interest-rate increases, "one would expect substantial negative impacts on real GDP and inflation in 2023 and 2024."

This story is passed around like well worn truth. However, we'll see that it's actually much less founded than you may think. Today, I'll look at simple facts. In my next post, I'll look at current empirical work, and we'll find that support for the standard view is much weaker than you might think. Then, I'll look at theory. We'll find that contemporary theory (i.e. for the last 30 years) is strained to come up with anything like the standard view.

Wednesday, August 2, 2023

Fitch is right

(Updated to fix numbers.) Fitch is right to downgrade the US. Read the sober report. But there are a few other reasons, or emphasis they might have added.

- The inflationary default.

Inflation is the economic equivalent of a partial default. The debt was sold under a 2% inflation target, and people expected that or less inflation. The government borrowed and printed $5 Trillion with no plan to pay it back, devaluing the outstanding debt as a result. Cumulative inflation so far means debt is repaid in dollars that are worth 10% less than if inflation had been* 2%. That's economically the same as a 10% haircut.

Thursday, July 27, 2023

On the 2% inflation target

Project Syndicate asked Mike Boskin, Brigitte Granville, Ken Rogoff and me whether 2% is the right inflation target. See the link for the other views. I pretty much agree with them in the short run -- don't mess with it -- but took a different long run view. Apparently Volcker and Greenspan were fans of price level targeting and hoped to get there eventually, which is the sort of long run approach I took here.

I also emphasize that any inflation target is (of course) a joint target of fiscal as well as monetary policy. Fiscal policy needs to commit to repay debt at the inflation target.

My view:

No, 2% is not the right target. Central banks and governments should target the price level. That means not just pursuing 0% inflation, but also, when inflation or deflation unexpectedly raise or lower the price level, gently bringing the price level back to its target. (I say “and governments” because inflation control depends on fiscal policy, too.)

The price level measures the value of money. We don’t shorten the meter 2% every year. Confidence in the long-run price level streamlines much economic, financial, and monetary activity. The corresponding low interest rates allow companies and banks to stay awash in liquidity at low cost. A commitment to repay debt without inflation also makes government borrowing easier in times of war, recession, or crisis.

Wednesday, July 5, 2023

Fiscal inflation and interest rates

Economics is about solving lots of little puzzles. At a July 4th party, a super smart friend -- not a macroeconomist -- posed a puzzle I should have understood long ago, prompting me to understand my own models a little better.

How do we get inflation from the big fiscal stimulus of 2020-2021, he asked? Well, I answer, people get a lot of government debt and money, which they don't think will be paid back via higher future taxes or lower future spending. They know inflation or default will happen sooner or later, so they try to get rid of the debt now while they can rather than save it. But all we can do collectively is to try to buy things, sending up the price level, until the debt is devalued to what we expect the government can and will pay.

OK, asked my friend, but that should send interest rates up, bond prices down, no? And interest rates stayed low throughout, until the Fed started raising them. I mumbled some excuse about interest rates never being very good at forecasting inflation, or something about risk premiums, but that's clearly unsatisfactory.

Of course, the answer is that interest rates do not need to move. The Fed controls the nominal interest rate. If the Fed keeps the short term nominal interest rate constant, then nominal yields of all bonds stay the same, while fiscal inflation washes away the value of debt. I should have remembered my own central graph:

This is the response of the standard sticky price model to a fiscal shock -- a 1% deficit that is not repaid by future surpluses -- while the Fed keeps interest rates constant. The solid line is instantaneous inflation, while the dashed line gives inflation measured as percent change from a year ago, which is the common way to measure it in the data.Monday, June 12, 2023

Papers: Dew-Becker on Networks

I've been reading a lot of macro lately. In part, I'm just catching up from a few years of book writing. In part, I want to understand inflation dynamics, the quest set forth in "expectations and the neutrality of interest rates," and an obvious next step in the fiscal theory program. Perhaps blog readers might find interesting some summaries of recent papers, when there is a great idea that can be summarized without a huge amount of math. So, I start a series on cool papers I'm reading.

Today: "Tail risk in production networks" by Ian Dew-Becker, a beautiful paper. A "production network" approach recognizes that each firm buys from others, and models this interconnection. It's a hot topic for lots of reasons, below. I'm interested because prices cascading through production networks might induce a better model of inflation dynamics.

(This post uses Mathjax equations. If you're seeing garbage like [\alpha = \beta] then come back to the source here.)

To Ian's paper: Each firm uses other firms' outputs as inputs. Now, hit the economy with a vector of productivity shocks. Some firms get more productive, some get less productive. The more productive ones will expand and lower prices, but that changes everyone's input prices too. Where does it all settle down? This is the fun question of network economics.

Ian's central idea: The problem simplifies a lot for large shocks. Usually when problems are complicated we look at first or second order approximations, i.e. for small shocks, obtaining linear or quadratic ("simple") approximations.

Wednesday, May 24, 2023

Hoover Monetary Policy Conference Videos

The videos from the Hoover Monetary Policy Conference are now online here. See my previous post for a summary of the conference.

The big picture is now clearer to me. Phil Jefferson rightly asked, what do you mean off track? Monetary policy is doing fine. Interest rates are, in his view, where they should be. He argued the case well.

But now I have an answer: The Fed has had three significant institutional failures: 1) Its inflation target is 2%, yet inflation exploded to 8%. The Fed did not forecast it, and did not see it even as it was happening. (Nor did many other forecasters, pointing to deeper conceptual problems.) 2) In the SVB and subsequent mess, the Fed's regulatory apparatus did not see or do anything about plain vanilla interest-rate risk combined with uninsured deposits. 3) I add a third, that nobody else seems to complain about: In 2020 starting with treasury markets, moving on to money market funds, state and local financing, and then an astonishing "whatever it takes" that corporate bond prices shall not fall, the Fed already revealed that the Dodd-Frank machinery was broken. (Will commercial real estate be next?)

Yet there is very little appetite for self-examination or even external examination. How did a good institution, filled with good, honest, smart and devoted public servants fail so badly? That's not "off-track" that's a derailment.

Well, two sessions at the conference begin to ask those questions, and the others aimed at the same issues. Hopefully they will prod the Fed to do so as well, or at least to be interested in other's answers to those questions.

(My minor contributions: on why the Taylor rule is important here, where I think I did a pretty good job; and comments on why inflation forecasts went so wrong at 1:00:16 here.)

Tuesday, May 16, 2023

Hoover Monetary Policy Conference

Friday May 12 we had the annual Hoover monetary policy conference. Hoover twitter stream here. Conference webpage and schedule here (update 5/24 now contains videos.) As before, the talks, panels, and comments will eventually be written and published.

The Fed has experienced two dramatic institutional failures: Inflation peaking at 8%, and a rash of bank failures. There were panels focused on each, and much surrounding discussion.

Monday, May 15, 2023

FTPL 50% off sale

Princeton University Press has a 50% off sale on all books, including the (overpriced, sorry) Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. The splash page also offers 30% off if you give them your email, but I'm not sure if they add.

Thursday, April 20, 2023

How do interest rates lower inflation?

A few days ago I gave a short talk on the subject. I was partly inspired by a little comment made at a seminar, roughly "of course we all know that if prices are sticky, higher nominal rates raise higher real rates, that lowers aggregate demand and lowers inflation." Maybe we "know" that, but it's not as readily present in our models as we think. This also crystallizes some work in the ongoing "Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates" project.

The equations are the utterly standard new-Keynesian model. The last equation tracks the evolution of the real value of the debt, which is usually in the footnotes of that model.

OK, top right, the standard result. There is a positive but temporary shock to the monetary policy rule, u. Interest rates go up and then slowly revert. Inflation goes down. Hooray. (Output also goes down, as the Phillips Curve insists.)

The next graph should give you pause on just how you interpreted the first one. What if the interest rate goes up persistently? Inflation rises, suddenly and completely matching the rise in interest rate! Yet prices are quite sticky -- k = 0.1 here. Here I drove the persistence all the way to 1, but that's not crucial. With any persistence above 0.75, higher interest rates give rise to higher inflation.

What's going on? Prices are sticky, but inflation is not sticky. In the Calvo model only a few firms can change price in any instant, but they change by a large amount, so the rate of inflation can jump up instantly just as it does. I think a lot of intuition wants inflation to be sticky, so that inflation can slowly pick up after a shock. That's how it seems to work in the world, but sticky prices do not deliver that result. Hence, the real interest rate doesn't change at all in response to this persistent rise in nominal interest rates. Now maybe inflation is sticky, costs apply to the derivative not the level, but absolutely none of the immense literature on price stickiness considers that possibility or how in the world it might be true, at least as far as I know. Let me know if I'm wrong. At a minimum, I hope I have started to undermine your faith that we all have easy textbook models in which higher interest rates reliably lower inflation.

(Yes, the shock is negative. Look at the Taylor rule. This happens a lot in these models, another reason you might worry. The shock can go in a different direction from observed interest rates.)

Panel 3 lowers the persistence of the shock to a cleverly chosen 0.75. Now (with sigma=1, kappa=0.1, phi= 1.2), inflation now moves with no change in interest rate at all. The Fed merely announces the shock and inflation jumps all on its own. I call this "equilibrium selection policy" or "open mouth policy." You can regard this as a feature or a bug. If you believe this model, the Fed can move inflation just by making speeches! You can regard this as powerful "forward guidance." Or you can regard it as nuts. In any case, if you thought that the Fed's mechanism for lowering inflation is to raise nominal interest rates, inflation is sticky, real rates rise, output falls and inflation falls, well here is another case in which the standard model says something else entirely.

Panel 4 is of course my main hobby horse these days. I tee up the question in Panel 1 with the red line. In that panel, the nominal interest are is higher than the expected inflation rate. The real interest rate is positive. The costs of servicing the debt have risen. That's a serious effect nowadays. With 100% debt/GDP each 1% higher real rate is 1% of GDP more deficit, $250 billion dollars per year. Somebody has to pay that sooner or later. This "monetary policy" comes with a fiscal tightening. You'll see that in the footnotes of good new-Keynesian models: lump sum taxes come along to pay higher interest costs on the debt.

Now imagine Jay Powell comes knocking to Congress in the middle of a knock-down drag-out fight over spending and the debt limit, and says "oh, we're going to raise rates 4 percentage points. We need you to raise taxes or cut spending by $1 trillion to pay those extra interest costs on the debt." A laugh might be the polite answer.

So, in the last graph, I ask, what happens if the Fed raises interest rates and fiscal policy refuses to raise taxes or cut spending? In the new-Keynesian model there is not a 1-1 mapping between the shock (u) process and interest rates. Many different u produce the same i. So, I ask the model, "choose a u process that produces exactly the same interest rate as in the top left panel, but needs no additional fiscal surpluses." Declines in interest costs of the debt (inflation above interest rates) and devaluation of debt by period 1 inflation must match rises in interest costs on the debt (inflation below interest rates). The bottom right panel gives the answer to this question.

Review: Same interest rate, no fiscal help? Inflation rises. In this very standard new-Keynesian model, higher interest rates without a concurrent fiscal tightening raise inflation, immediately and persistently.

Fans will know of the long-term debt extension that solves this problem, and I've plugged that solution before (see the "Expectations" paper above).

The point today: The statement that we have easy simple well understood textbook models, that capture the standard intuition -- higher nominal rates with sticky prices mean higher real rates, those lower output and lower inflation -- is simply not true. The standard model behaves very differently than you think it does. It's amazing how after 30 years of playing with these simple equations, verbal intuition and the equations remain so far apart.

The last two bullet points emphasize two other aspects of the intuition vs model separation. Notice that even in the top left graph, higher interest rates (and lower output) come with rising inflation. At best the higher rate causes a sudden jump down in inflation -- prices, not inflation, are sticky even in the top left graph -- but then inflation steadily rises. Not even in the top left graph do higher rates send future inflation lower than current inflation. Widespread intuition goes the other way.

In all this theorizing, the Phillips Curve strikes me as the weak link. The Fed and common intuition make the Phillips Curve causal: higher rates cause lower output cause lower inflation. The original Phillips Curve was just a correlation, and Lucas 1972 thought of causality the other way: higher inflation fools people temporarily to producing more.

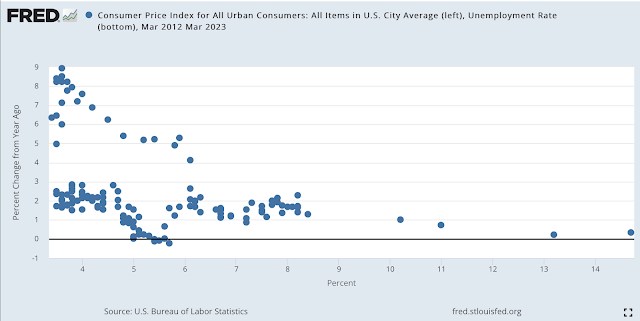

Here is the Phillips curve (unemployment x axis, inflation y axis) from 2012 through last month. The dots on the lower branch are the pre-covid curve, "flat" as common wisdom proclaimed. Inflation was still 2% with unemployment 3.5% on the eve of the pandemic. The upper branch is the more recent experience.

I think this plot makes some sense of the Fed's colossal failure to see inflation coming, or to perceive it once the dragon was inside the outer wall and breathing fire at the inner gate. If you believe in a Phillips Curve, causal from unemployment (or "labor market conditions") to inflation, and you last saw 3.5% unemployment with 2% inflation in February 2021, the 6% unemployment of March 2021 is going to make you totally ignore any inflation blips that come along. Surely, until we get well past 3.5% unemployment again, there's nothing to worry about. Well, that was wrong. The curve "shifted" if there is a curve at all.

But what to put in its place? Good question.

Update:

Lots of commenters and correspondents want other Phillips Curves. I've been influenced by a number of papers, especially "New Pricing Models, Same Old Phillips Curves?" by Adrien Auclert, Rodolfo Rigato, Matthew Rognlie, and Ludwig Straub, and "Price Rigidity: Microeconomic Evidence and Macroeconomic Implications" by Emi Nakamura and Jón Steinsson, that lots of different micro foundations all end up looking about the same. Both are great papers. Adding lags seems easy, but it's not that simple unless you overturn the forward looking eigenvalues of the system; "Expectations and the neutrality of interest rates" goes on in that way. Adding a lag without changing the system eigenvalue doesn't work.

Thursday, March 2, 2023

Lessons from Sargent and Leeper

At the AEI fiscal theory event last Tuesday Tom Sargent and Eric Leeper made some key points about the current situation, with reference to lessons of history.

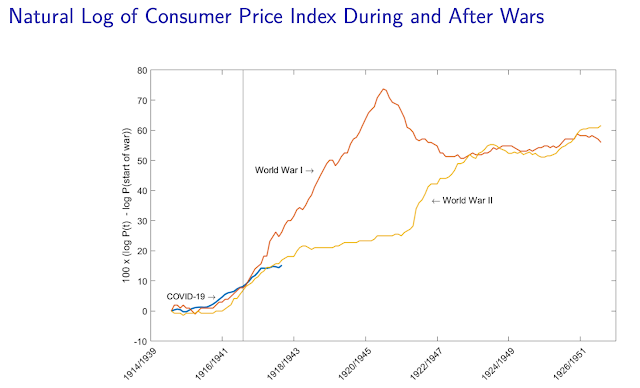

Tom's comments updated his excellent paper with George Hall "Three World Wars" (at pnas, summary essay in the Hoover Conference volume). Tom and George liken covid to a war: a large emergency requiring immense expenditure. We can quibble about "require" but not the expenditure.

(2008 was a little war in this sense as well.) Since outlays are well ahead of receipts, these huge temporary expenditures are financed by issuing debt and printing money, as optimal tax theory says they should be.

In all three cases, you see a ratcheting up of outlays after the war. That's happening now, and in 2008, just as in WWI and WWII.

After WWI and WWII, there is a period of primary surpluses -- tax receipts greater than spending -- which helps to pay back the debt. This time is notable for the absence of that effect.

We see that most clearly by plotting the primary deficits directly. The data update since Tom and George's original paper (dots) makes that clear. To a fiscal theorist, this is a worrisome difference. We are not following historical tradition of regular, full employment, peacetime surpluses.

The two world wars were also financed by a considerable inflation. The important consequence of inflation is that it inflates away government debt. Essentially, we pay for part of the war by a default on debt, engineered via inflation.

Tuesday, February 28, 2023

FTPL Videos

Two great videos just dropped related to fiscal theory.

The first is an "Uncommon Knowledge" interview with Peter Robinson. We start with fiscal theory and move on far and wide. Peter is a great interviewer, and the Uncommon Knowledge production team put together a great video of it. Pick your link: Video at Hoover (best, in my view); Hoover event page with podcast, links and more info, Youtube, Twitter, Facebook.

Second, Michael Strain at AEI moderated a great panel discussion on fiscal theory with me, Robert Barro, Tom Sargent and Eric Leeper. Three of the founding fathers of fiscal theory offer thoughtful comments, and Michael had provocative questions. I start with a 20 minute presentation, with slides, so this is the most compact "what is the fiscal theory" video to date. It's at the AEI event page or Youtube

Saturday, January 21, 2023

A fiscal theory fest at AEI, launch podcast, and official release.

Mark your calendars! February 28th 3:00 PM eastern the AEI's Michael Strain will host a zoom event on Fiscal Theory of the Price Level. Info and registration here.

This event will be particularly good because Michael convinced Robert Barro, Tom Sargent, and Eric Leeper to come and discuss. These are the giants on whose shoulders I meekly stand.

Robert Barro did the modern version of "Ricardian Equivalence." If people look at government debt and understand that there will be taxes to pay it off, they save and the deficit (with lump sum taxes) has no effect. He also did the modern version of tax smoothing. It is good government policy to borrow in bad times, and repay in good times, with steady low taxes, rather than raise distorting tax rates a lot in bad times. Both underlie fiscal theory,

Tom Sargent, with Neil Wallace wrote “Unpleasant Monetarist Arithmetic,” the cornerstone of the modern fiscal theory. They pointed out that if fiscal policy is stuck in deficits, monetary policy can only choose to inflate now or inflate later. Tom went on to write many fantastic papers on the theory of fiscal-monetary interactions, and on their place in economic history. His "ends of four big inflations" showed that the great post WWI hyperinflations ended when the fiscal problem was solved, involving no monetary stringency. A good lesson, now mostly forgotten in the widespread view that ending inflation must come with misery. His Nobel speech “United States Then, Europe Now” is a great example of historical work. In my view, the Nobel Committee should have given him a prize for monetary-fiscal interactions, which is even better than the econometric work they cited. Maybe he'll be the first economist to get two.

Eric Leeper is the original innovator of the modern fiscal theory in his paper "Equilibria under ‘active’ and ‘passive’ monetary and fiscal policies. " Eric put fiscal theory in the context of interest rate targets, r rather than money supply, which is how all our central bankers operate, and includes nominal rather than real debt. Thus, he integrates fiscal theory with how our monetary policy actually works, creates the essential model of inflation under interest rate targets, and integrates fiscal theory with modern new-Keynesian or general equilibrium models that are 99% of all applied work.

I'm going to try to be as brief as possible so we can hear from these amazing economists, plus Michael, no slouch himself. This much talent can't possibly sit still and not say things that are a bit critical, and thought provoking.

****

Vince Ginn of the "Let People Prosper" Podcast did a very nice interview on FTPL. Like many economists, Vince has a good monetarist heart, and explaining the difference between FTPL and monetarism was useful for me.

****

As of January 17, The Fiscal Theory of the Price Level is formally released! Along with this good news, I have some bad news -- I have to take down the free version on my website. However, keep that in mind for the (sadly) evolving typo list, sample chapters, online appendix, follow on essays, and revisions as they come. I already have a revised Chapter 5 posted, which does a better job of introducing fiscal theory in standard new-Keynesian models.