Abstract

Despite wide public support for gender equality in work and caregiving, family responsibilities are still divided predominantly along traditional gender lines. This study examined the role of biological essentialism in the division of family roles using a nationally representative sample of British parents with young children (N = 5,605). Both mothers’ and fathers’ essentialist beliefs about men’s and women’s innate ability to care for children were associated with a more traditional division of childcare tasks, more hours of childcare provided by the mother, and fewer hours of childcare provided by the father. When gender role attitudes were considered together with biological essentialism, only essentialism was a significant predictor of involvement in childcare. Finally, the results supported our predictions that the effect of biological essentialism is mediated through parents’ work hours, and that essentialism affects mothers’ and fathers’ involvement in work and childcare in opposite directions. Taken together, the findings suggest that essentialist beliefs are a key hindrance to greater gender equality because they motivate parents to divide roles according to traditional gender norms. These findings may be of particular interest to practitioners and policy makers interested in increasing fathers’ involvement in childcare, mothers’ participation in the labor force, and overall gender equality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Discover the latest articles and news from researchers in related subjects, suggested using machine learning.Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Over the past several decades, men’s and women’s participation in paid and unpaid work has become more similar, with the gender gap in family responsibilities gradually narrowing (Altintas & Sullivan, 2017; Bianchi & Milkie, 2010; Sullivan et al., 2018). This convergence reflects a dramatic increase in mothers’ participation in paid labor, coupled with a more modest increase in fathers’ involvement in childcare (Pailhé et al., 2021; Schoppe-Sullivan & Fagan, 2020). Despite these changes, family roles are still divided predominantly along traditional gendered norms, with mothers carrying the main responsibility for caregiving and fathers for breadwinning (Craig & Mullan, 2011; Yavorsky et al., 2015). This gender inequality disadvantages women in the workplace (Gershuny, 2004; Maume, 2006) and denies men the opportunity to develop close nurturing relationships with their children as primary caregivers (Deutsch & Gaunt, 2020; Joshi, 2021).

A large body of research has been devoted to explaining this persistent inequality in work and care (Craig & Mullan, 2011; Perry-Jenkins & Gerstel, 2020; Sullivan et al., 2018). In this article, we examine the role played by parents’ essentialist views in determining their time with children and the division of childcare tasks. Drawing on Bem’s (1993) analysis of biological essentialism as a gender lens, we posit that parents’ tendency to perceive men and women as inherently different in their innate ability to take care of children guides their choices regarding the division of family responsibilities. Despite preliminary evidence from both quantitative (Gaunt, 2006; Ross-Plourde et al., 2022) and qualitative studies (Deutsch, 1999; Deutsch & Gaunt, 2020) for the importance of such essentialist beliefs, research examining these beliefs is scant, and all the evidence we have comes from small nonrepresentative samples. Mediating and moderating factors have also remained largely unexplored.

To better establish the effect of biological essentialism and examine its underlying mechanisms, we carried out an original, nationally representative survey of British parents with young children. We argue that essentialist perceptions explain involvement in childcare beyond the contribution of gender role attitudes which have been more widely researched (e.g., Aassve et al., 2014; Bulanda, 2004). We further suggest that each parent’s essentialist perceptions affect not only their own involvement in childcare but also the involvement of their partner. Finally, we argue that paid work hours mediate the effect of parents’ essentialism, and that gender moderates this effect, as essentialism affects men’s and women’s involvement in work and childcare in opposite directions. Understanding the role played by biological essentialism may shed light on one of the key barriers to greater gender equality in work and childcare and help to explain the gap between the wide public support for gender equality and the predominantly traditional allocation of family roles.

Determinants of Parents’ Involvement in Childcare

Several theoretical frameworks have been applied to explain the division of housework and childcare. Early research drew on economic, structural or exchange perspectives (Becker, 1981; Bergen, 1991), suggesting that couples assign tasks based on a rational consideration of how to achieve maximum efficiency, or that the allocation of tasks results from economic bargaining in which the partner with greater power can negotiate lower participation in household labor (Coverman, 1985; Deutsch et al., 1993). This body of research focused mainly on parents’ socioeconomic and employment characteristics and showed that the father’s involvement in childcare decreases the more hours he works and the higher his income, and increases the more hours the mother works for pay (Deutsch et al., 1993; Yeung et al., 2001). More recently, studies have drawn attention to the impact of family structures (Carlson et al., 2011; Kendig & Bianchi, 2008), paternity leave duration (Petts & Knoester, 2018) and cultural and institutional contexts (Craig & Mullan, 2010; Hook & Wolf, 2012; Kan et al., 2011) on parents’ time with children.

Other lines of research emphasized the psychological processes involved in decisions about employment and childcare, including couples’ negotiations and rationalizations (Daminger, 2020; Deutsch, 1999; Mannino & Deutsch, 2007). These interaction processes have been theorized as attempts to either “do gender” by exhibiting appropriately gendered behaviors (West & Zimmerman, 1987) or “undo gender” by resisting prescriptive gendered norms of fatherhood and motherhood (Deutsch, 2007; Deutsch & Gaunt, 2020; Risman, 2009).

Closer to the present study’s approach, research has shown that parents’ decisions are guided by their social psychological characteristics such as their value priorities (Gaunt, 2005, 2019), the centrality of their parental and work-related identities (Gaunt & Scott, 2014; Goldberg, 2015; Pinho & Gaunt, 2022), and fathers’ adherence to old and new masculinity ideologies (Kaplan & Offer, 2022; Offer & Kaplan, 2021; Shafer et al., 2021). However, the most widely researched social psychological explanation of involvement in work and childcare is gender role attitudes (also referred to as gender ideology), defined as “individuals’ level of support for a division of paid work and family responsibilities that is based on this notion of separate spheres [for men and women]” (Davis & Greenstein, 2009, p. 89). This approach suggests that couples who endorse traditional gender ideology allocate roles along traditional lines, such that the father is the main breadwinner and the mother is the main caregiver, whereas those who endorse egalitarian views share these roles more equally. While findings generally support the association between gender role attitudes and housework (Aassve et al., 2014; Kan, 2008), the evidence regarding childcare is mixed (Bulanda, 2004; Wang & Cheung, 2023) and in recent longitudinal studies gender attitudes did not contribute to explaining involvement in childcare (Kuo et al., 2018; Ross-Plourde et al., 2022). Moreover, criticisms suggest that the concept of attitudes toward gender roles is too simplistic and obscures distinct attitudinal dimensions, and that its measures are generally outdated (Halimi et al., 2018; Knight & Brinton, 2017; Maineri et al., 2021; Scarborough et al., 2019; Walter, 2018). We argue that beliefs in biological essences may co-exist with egalitarian gender attitudes and are more directly relevant to caring behaviors and may therefore provide a better attitudinal account of the division of work and childcare.

Biological Essentialism and the Division of Work and Childcare

In his seminal work on the cognitive process of categorization, Medin (1989) argued that categories are organized around lay theories about the deeper features of the category members. That is, people categorize others based on surface characteristics, assuming that these characteristics are expressions of an underlying invisible essence that makes the group members what they are. For example, people categorize individuals as male and female based on surface features such as height, voice, or facial hair, but believe that these features are cues to some deep underlying masculine or feminine essence (Medin, 1989). In the ___domain of parenthood, findings suggest that the salient visual changes women go through during pregnancy heighten essentialist perceptions of motherhood (Park et al., 2015), and thus biological mothers are perceived in more essentialist terms (i.e., as a distinct natural category) than both fathers and adoptive mothers.

Biological essentialism was introduced by Bem (1993) as one of three gender lenses that are embedded in the historical and contemporary discourses and explain gender hierarchies in Western culture. In her ground-breaking analysis, Bem argued that the lens of biological essentialism rationalizes and legitimizes gender polarization and male dominance, by treating them as the natural and inevitable consequences of the intrinsic biological natures of women and men. Her analysis revealed biological theorists’ tendency to overemphasize biology and underemphasize historical and social contexts, which makes gender inequalities seem innate and unavoidable rather than historically constructed and modifiable. Bem further outlined the process by which individuals internalize these culturally embedded gender lenses and develop consistent identities. In this way, biological essentialism perpetuates the notion of inevitable gender differences in abilities, expectations, and roles, and naturalizes gender inequalities (Bem, 1993).

Drawing on Medin’s work on categorization and Bem’s analysis of biological essentialism, Gaunt (2006) suggested that viewing men and women as essentially different in their innate caring abilities informs parents’ choices regarding the appropriate level of their involvement in childcare. That is, couples who view women as having an essence that makes them inherently more suitable for childcare would be reluctant to share childcare responsibilities, whereas couples who view men and women as similar would share more equally. In a sample of Israeli couples, Gaunt (2006) found that fathers’ essentialist perceptions were the strongest and most consistent predictor of their involvement in childcare, including their share of daily physical care, social and emotional care, and overall responsibility for childcare. Ross-Plourde et al. (2022) replicated and extended these findings in a longitudinal sample of Canadian couples expecting their first child. They measured a range of attitudes including gender ideology, the importance attributed to the father role, and the perceived consequences of involvement for children. Their findings showed that men’s biological essentialism was the only attitude that significantly accounted for their involvement intentions before the birth. That is, the more they viewed men and women as essentially different in their ability to provide care, the lower were their intentions to be involved in childcare. In turn, fathers’ prenatal involvement intentions, together with mothers’ postnatal biological essentialism, were the strongest predictors of the fathers’ involvement in childcare when their baby was 2–3 months old (Ross-Plourde et al., 2022).

Additional evidence for the importance of essentialism comes from three studies in which mothers’ endorsement of essentialist attitudes was associated with their overall division of housework and childcare (Liss et al., 2013; Thorsteinsen et al., 2022), mediated through their maternal gatekeeping tendencies (Pinho & Gaunt, 2021). In addition, these studies found stronger endorsement of essentialist views among stay-at-home mothers compared to mothers who worked for pay (Liss et al., 2013), and among parents who maintained a traditional allocation of roles compared to those who reversed roles (Pinho & Gaunt, 2021). Essentialist beliefs might operate through the expectations they set, as college women who rejected essentialism had higher expectations for an equal division of childcare with their future husbands (Deutsch et al., 2007). Among men, the effect might be mediated by self-efficacy, as expecting fathers’ essentialist perceptions predicted their reduced parenting self-efficacy at three months postpartum (Donithen & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2022).

Taken together, these initial findings suggest that biological essentialism may play an important role in couples’ decisions about the allocation of work and childcare responsibilities, above and beyond their gender role attitudes. Nevertheless, only a handful of studies to date have examined parents’ essentialist beliefs, and all the evidence we have comes from relatively small, nonrepresentative samples. To better establish the role of essentialism, we recruited a large, nationally representative sample of British parents to test the hypothesis that endorsement of essentialist views about men’s and women’s innate parenting abilities will be associated with involvement in childcare. Specifically, we predicted that after controlling for the effect of gender role attitudes, mothers’ essentialist views (Hypothesis 1) would be positively related to their share of childcare tasks relative to their partners (H1a) and their hours of childcare (H1b), and negatively related to their partners’ hours of childcare (H1c). Conversely, we predicted that fathers’ essentialist views (Hypothesis 2) would be negatively related to their relative share of childcare tasks (H2a) and their hours of childcare (H2b), and positively related to their partners’ hours of childcare (H2c).

Moderated Mediation by Work Hours and Gender

Couples’ decisions about the division of childcare responsibilities are closely linked with their decisions about paid work. Time constraints mean that a parent’s investment of time in paid work has implications for both their own and their partner’s time investment in childcare, and consequently their share of childcare tasks. Many studies have shown that work hours are negatively correlated with involvement in childcare for both fathers and mothers (Bünning, 2020; Kaplan & Offer, 2022; Norman et al., 2014), and that a parent’s work hours are positively correlated with their partner’s involvement in childcare (Buchanan et al., 2016; Raley et al., 2012).

Time availability model proposes work hours as a major determinant of involvement in housework and childcare (e.g., Horne et al., 2018), however growing evidence suggests that levels of involvement in both paid work and childcare are guided by parents’ value priorities, identities, and ideologies (Gaunt, 2005, 2019; Gaunt & Scott, 2014; Huffman et al., 2014). Particular attention has been given to the effect of gender ideologies on parents’ work hours (Andringa et al., 2015; Kaufman & Uhlenberg, 2000; Stertz et al., 2017). Longitudinal studies in several countries showed that men’s and women’s prenatal egalitarian attitudes predicted lower reduction in mothers’ work hours after birth and (to a lesser extent) larger reductions in fathers’ work hours (Gaunt, 2019; Khoudja & Fleischmann, 2018; Schober & Scott, 2012; Stertz et al., 2017). Whereas the effect of gender role attitudes on work hours is well established, to our knowledge no research to date has examined the associations between essentialist views and work hours. We expect biological essentialism to affect parents’ work hours along similar lines, such that mothers’ essentialist views will be associated with fewer work hours and fathers’ essentialist views will be associated with longer work hours.

Based on the rationale delineated above, we propose that parents’ essentialist beliefs guide their choices about work hours, and these in turn partially determine their time investment in childcare and the allocation of childcare tasks. We therefore predicted that work hours would mediate the effect of biological essentialism on involvement in childcare tasks and hours of care by self and partner (Hypothesis 3). We further predicted that this mediation by work hours would be moderated by gender (Hypothesis 4). Specifically, in women, higher endorsement of essentialism will be associated with fewer hours of paid work, which in turn, will be associated with a greater share of childcare tasks relative to their partners, more hours of childcare, and fewer hours of childcare provided by their partner. Conversely, we hypothesized that men’s endorsement of biological essentialism would be associated with more hours of paid work, which in turn, would be associated with a smaller share of childcare tasks relative to their partners, fewer hours of childcare, and more hours of childcare provided by their partner.

The Present Study

To test our hypotheses regarding the associations between parents’ essentialist beliefs and their involvement in work and childcare, we recruited a large, nationally representative sample of British parents living with a different-sex partner and at least one child aged 11 or under. In the UK, as in other developed countries, men’s and women’s involvement in paid work and childcare has become increasingly similar over the past decades (Altintas & Sullivan, 2017); however family roles are still divided along traditional gendered norms (Craig & Mullan, 2011). Compared to other European countries, British men’s work hours are among the longest (Eurostat, 2022), mothers’ employment rates are among the highest, but rates of mothers’ full-time employment are among the lowest (Costa Dias et al., 2020; Kanji, 2011). These characteristics can be attributed partly to gendered policies around paternity and maternity leave as well as the lack of state provision of childcare for young children.

Against this backdrop of a dominant male-breadwinner/part-time female-caregiver model, we explored parents’ essentialist beliefs about men’s and women’s innate parenting abilities and their associations with the division of family roles. We expected essentialism to play an important role in parents’ decisions, beyond the role played by their gender role attitudes. We also expected mutual influences of each parent’s essentialist beliefs on their partner’s involvement in work and childcare. Finally, we predicted that the effect of parents’ essentialist beliefs would be mediated by their work hours, so that mothers’ essentialism would be related to shorter work hours and greater involvement in childcare, whereas fathers’ essentialism would be related to longer work hours and lower involvement in childcare.

Method

Sample and Procedure

We used original data collected from a nationally representative sample of British parents as part of a larger research project on work and childcare (Gaunt et al., 2022). The sample comprised 5,605 adults, consisting of independent samples of 2,805 men and 2,800 women. Participants were married/cohabiting with a different-sex partner and had biological child/ren together, with at least one child aged 11 or under. Descriptive statistics for the sample are shown in Table 1. Data were gathered in February 2020 using an online survey administered by YouGov, a research company that maintains a UK panel of 800,000 + individuals. Emails were sent to panelists selected at random from the base sample of the required profile. The responding sample was weighted to the profile of the sample definition based on census data to provide a representative reporting sample. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Lincoln Research Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the study.

Measures

Hours of Childcare

To assess involvement in childcare in terms of time investment, the participants reported the number of hours per week during which they were the sole care providers when the child was awake, and the number of hours per week in which their partner was the sole care provider when the child was awake.

Share of Childcare Tasks

To assess involvement in childcare in terms of task performance, a “Who does what?” measure asked participants to indicate their involvement relative to their partner in 19 childcare tasks (adapted from Gaunt & Scott, 2014). The tasks were selected to reflect daily physical care activities (feeding, dressing, putting to bed), social and emotional care (reading, playing, helping with social/emotional problems), and management/responsibility for childcare (planning activities, scheduling meetings, choosing daycare/school). Participants were asked: “In the division of labor between you and your partner, which of you does each of these tasks?” Responses were indicated on a 5-point scale ranging from almost always my spouse (1) through my spouse more than myself (2), both of us equally (3), and myself more than my spouse (4) to almost always myself (5). Participants were also given the opportunity to rate not applicable to my child (9), which was treated as missing data. An average of the 19 task ratings was calculated to obtain a score of total involvement in childcare tasks. Higher scores on this measure indicated greater involvement of the participant relative to their partner. Cronbach’s alpha for this measure was 0.94 for women and 0.88 for men.

Biological Essentialism

Parents’ essentialist views of men’s and women’s innate competence as parents were assessed using Gaunt’s (2006) essentialist perceptions scale. This scale consists of seven statements which reflect essentialist beliefs about the inherently different abilities of mothers and fathers (“Fathers have to learn what mothers are able to do naturally;” “Maternal instincts enable mothers to identify baby’s needs”) as well as statements which reflect rejection of essentialist beliefs (“Men could nurture like women”). Participants indicated their level of agreement with each statement using a scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Responses were recoded and averaged so that a high score reflected greater endorsement of essentialist perceptions. Cronbach’s alphas for this measure were 0.86 for women and 0.87 for men.

Gender Role Attitudes

Parents’ attitudes toward gender roles were measured using Gaunt’s (2006) 5-item scale which assesses traditional and egalitarian attitudes (e.g., “It is best for everyone if the man earns a living and the woman takes care of the home and children;” “Men and women should share housework when both are employed”). Participants rated their level of agreement with each statement using a 5-point scale ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Responses were recoded so that a high score reflected more egalitarian attitudes toward gender. The average score for the five items was computed to measure the participant’s gender role attitudes. Cronbach’s alphas for this measure were 0.71 for women and 0.72 for men.

Sociodemographic Variables

Participants indicated their gender, age, level of education, work hours, income, ethnicity, and geographical region (see Table 1). They also reported the number of children in the household the age of each child.

Analytic Strategy

Descriptive statistics and Pearson correlations were first computed between biological essentialism, gender role attitudes, hours of paid work and childcare, and involvement in childcare tasks. To test the first two sets of hypotheses, we conducted a series of multiple regression analyses separately for fathers and mothers. In each analysis, a variable pertaining to one measure of involvement in childcare was regressed on the set of biological essentialism and gender role attitudes measures. These predictive variables were assessed for possible multicollinearity using tolerance and the variance inflation factor (VIF). However, there were no signs of multicollinearity in the regression models (VIF values ranged from 1.29 to 1.32, and tolerance values ranged from 0.75 to 0.77).

To test the third and fourth hypotheses about the moderated mediation of work hours in the relationship between biological essentialism and involvement in childcare, we followed the methods developed by Preacher and Hayes (Hayes, 2013; Preacher et al., 2007) for evaluating conditional indirect effects using the bootstrap procedure (Preacher & Hayes, 2004). Bootstrap resampling of the data provides estimates for the model paths and a confidence interval of these estimates. We evaluated a moderated mediation for each of the three outcome variables through the construction and estimation of a conditional process model (Hayes, 2013). All analyses were conducted using Hayes’ (2013) PROCESS macro with 1,000 bootstrap samples and bias-corrected confidence intervals.

Results

Preliminary Analysis

Missing data ranged from 0.6 to 2.1% for the study variables, therefore no missing data handling technics were applied. Table 2 presents the means, standard deviations, and Pearson correlations among the three measures of involvement in childcare, biological essentialism, gender role attitudes, and work hours. In both fathers and mothers, biological essentialism had moderate negative associations with egalitarian gender role attitudes (r = − .48 and r = − .49 respectively), suggesting that these two constructs reflect related but distinct ideologies. In line with our predictions, mothers’ biological essentialism was positively related to their involvement in childcare and negatively related to their work hours, whereas fathers’ biological essentialism was negatively related to their involvement in childcare and positively related to their work hours. Finally, replicating previous studies (Buchanan et al., 2016; Bünning, 2020; Kaplan & Offer, 2022), fathers’ and mothers’ work hours were negatively correlated with their hours of childcare and involvement in childcare tasks, and positively correlated with the partner’s hours of childcare.

Biological Essentialism and Involvement in Childcare

Our first and second sets of hypotheses suggested that parents’ biological essentialism would predict their involvement in childcare beyond the contribution of gender role attitudes. The results of the multiple regression analyses (Table 3) indicated that gender role attitudes were not a significant predictor in any of the regression equations. In line with Hypotheses 1a and 1b, the regression equations of mothers’ involvement in childcare tasks and hours of care were significant overall (Table 3, upper part), and mothers’ biological essentialism was a significant predictor in both of these regression analyses: the more the mother endorsed essentialist views of men and women as parents, the greater was her share of childcare tasks relative to her partner (β = 0.28, p < .001) and the more hours she spent providing childcare (β = 0.14, p < .001). However, mothers’ biological essentialism did not predict fathers’ hours of childcare and thus there was no support for Hypothesis 1c.

The results in Table 3 (bottom part) show further that the regression equations of fathers’ involvement in childcare tasks, hours of care, and partner’s hours of care were all significant, and father’s biological essentialism was a significant predictor in all these regression analyses. Supporting Hypothesis 2, the more the father endorsed essentialist views of men and women as parents, the smaller was his share of childcare tasks relative to the mother’s (β = − 0.28, p < .001), the fewer hours he spent providing childcare (β = − 0.08, p < .001), and the more hours the mother spent as the sole care provider (β = 0.08, p < .001).

Moderated Mediation by Work Hours and Gender

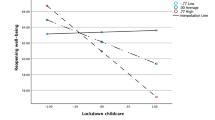

Our third and fourth hypotheses suggested that the effect of parents’ biological essentialism on their involvement in childcare would be mediated by their paid work hours (Hypothesis 3), and that this mediation effect would be moderated by gender (Hypothesis 4). To test these hypotheses, we constructed conditional models using a bootstrapping approach to assess the significance of the indirect effects of essentialism in mothers and fathers (Hayes, 2013). Specifically, we applied model 8 of the PROCESS program (Hayes, 2013) to assess three moderated mediation models. In each of these models, one of the three measures of childcare was the outcome variable and biological essentialism was the predictor variable, with work hours as the mediator and gender as the moderator. Table 4 presents bias-corrected bootstrap estimates and 95% confidence intervals of the indirect (mediated) effects and the overall moderated mediation model. Figures 1, 2 and 3 show the estimates of the separate paths for mothers and fathers for each of the three outcome variables: relative share of childcare tasks, hours of childcare, and partner’s hours of childcare.

In line with Hypothesis 3, work hours were a significant mediator in all three models, as reflected in significant conditional indirect effects of essentialism on involvement in childcare for both mothers and fathers. As can be seen in Table 4, the indirect effects of mothers’ essentialism on their share of childcare tasks and hours of care, and the indirect effect of fathers’ essentialism on their partner’s hours of care, were positive and significant, as the bootstrap confidence intervals for these effects were entirely above zero. Conversely, the indirect effects of fathers’ essentialism on their share of childcare tasks and hours of care, and the indirect effect of mothers’ essentialism on their partner’s hours of care, were negative and significant, as the bootstrap confidence intervals for these effects were entirely below zero. Supporting Hypothesis 3, these results indicate that the effects of parents’ essentialist views on their own and their partner’s involvement in childcare were mediated through their work hours.

The results in Table 4 show further that gender moderated this mediation effect of work hours, as indicated by indexes of moderated mediation (differences between mothers’ and fathers’ indirect effects) which were positive with bootstrap confidence intervals entirely above zero for involvement in childcare tasks [0.02, 0.03] and hours of care [0.70, 1.37], and negative with bootstrap confidence interval entirely below zero for partner’s hours of care [-0.97, -0.47]. These moderation effects are illustrated in Figs. 1, 2 and 3, as path a shows that fathers’ biological essentialism had a positive effect on their work hours, whereas mothers’ essentialism had a negative effect on their work hours. All in all, these results provide support for the moderated mediation process in the effect of mothers’ and fathers’ biological essentialism on involvement in childcare.

As for the direct effects of biological essentialism on involvement in childcare, Fig. 1 (path c’) shows that men’s biological essentialism had a direct negative effect on their share of childcare tasks whereas women’s essentialism had a direct positive effect on their own share of tasks. However, Fig. 2 (path c’) suggests that the direct effect of men’s biological essentialism on their hours of childcare was not significant, while Fig. 3 (path c’) shows that the direct effect of women’s biological essentialism on their partner’s hours of childcare was not significant. Taken together, these results suggest that the effects of parents’ essentialist beliefs on their involvement in childcare tasks and on mothers’ hours of care are partially mediated by their work hours, whereas the effects of fathers’ and mothers’ essentialist beliefs on fathers’ hours of care is fully mediated by work hours.

Discussion

In this study, we examined the role played by parents’ essentialist perceptions in their involvement in childcare. Drawing on Bem’s (1993) analysis of biological essentialism as a gender lens, we proposed that essentialist views explain involvement in childcare beyond the contribution of gender role attitudes. We predicted that a parent’s essentialism is related to both their own and their partner’s involvement in childcare. Furthermore, we argued that these associations are mediated through parents’ work hours, and that gender moderates this mediation process, such that essentialism contributes to men’s and women’s involvement in work and childcare in opposite directions.

The results fully supported our hypotheses by showing that both mothers’ and fathers’ essentialist beliefs were related to a more traditional division of childcare tasks, more hours of childcare provided by the mother, and fewer hours of childcare provided by the father. The findings thus replicated and extended those of previous studies (Gaunt, 2006; Ross-Plourde et al., 2022) by providing evidence for the role of essentialist views in a large representative sample of British parents. Replicating the findings in this context increases our confidence in their generalizability and further highlights the importance of parents’ beliefs about the innate nature of men and women as a barrier to greater gender equality.

Moreover, when gender role attitudes were considered together with biological essentialism, only essentialism was a significant predictor of involvement in childcare, while gender attitudes did not predict any of the outcome variables. Beliefs in innate gender differences may matter more to the division of family work than broader ideologies about gender equality. Attitudes towards women’s employment and men’s share of housework and childcare have changed and become more egalitarian over time (Scarborough et al., 2019), as reflected in our findings in the concentration of respondents on the egalitarian end of the scale (cf. Halimi et al., 2018). In comparison, views about innate differences between men and women seem more diverse, and endorsement of essentialism is more prevalent than traditional attitudes towards gender roles. Essentialist perceptions may thus have greater explanatory power than gender role attitudes and may account for previous findings about the relations between gender attitudes and involvement in childcare, as these attitudes correlate with essentialism. This is consistent with evidence from qualitative research in which egalitarian views were widespread among both couples who shared childcare equally and those who maintained a semi-traditional division (Gaunt et al., 2022), whereas rejection of biological essentialism appeared as necessary for an equal division of childcare (Deutsch, 1999; Deutsch & Gaunt, 2020).

Finally, the results supported our predictions that the contribution of biological essentialism is mediated through parents’ work hours, and that essentialism is related to mothers’ and fathers’ hours of work and care in opposite ways. Thus, stronger essentialist beliefs of both partners may lead fathers to invest more time in paid work which, in turn, leaves less time for childcare. Conversely, both partners’ stronger essentialist views lead mothers to work fewer hours and free more time for childcare, based on the belief that the mother is inherently more suitable than the father to look after children. Qualitative work reveals that decisions parents make about their work lives occur after children are born or in anticipation. Often couples justify an unequal division of labor by citing their differing work hours (Daminger, 2020; Deutsch, 1999). However, our findings suggest that the opposite direction of causality may also be plausible. Parents who believe in biological difference may make decisions about work, which then underwrite an unequal division between them. This may create a self-fulfilling prophecy as the parent who spends more time with children can become more skilled at childcare. The findings therefore shed light on one process through which essentialist beliefs guide parents’ behaviors, suggesting that these beliefs motivate parents to create a more traditional division of breadwinning and caregiving.

Interestingly, the association of both parents’ essentialism with fathers’ hours of care was fully mediated by work hours, whereas the association with mothers’ hours of care and the relative share of childcare tasks was only partially mediated. Rejection of essentialism only leads to greater paternal involvement through mothers’ longer work hours and fathers’ shorter work hours. In contrast, parents who endorse biological essentialism view mother care as irreplaceable, leading mothers to invest more time in childcare and perform more tasks partially regardless of their work hours.

Limitations and Future Research Directions

Some limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, the study focused on different-sex couples living together with their young children. Biological essentialism may have different associations with involvement in childcare in other family structures (e.g., single, same-sex or nonresident parents) or with older children. For example, in divorced/nonresident fathers, essentialist views of both parents may lead to even lower levels of father-child contact. Conversely, essentialist beliefs about women’s innate nurturing abilities may be particularly important in determining involvement with babies and toddlers and may seem less relevant as children grow older.

Another limitation is the cross-sectional nature of this study, which prevents us from drawing causal conclusions with confidence. Specifically, the associations between biological essentialism, work hours and childcare may reflect the effect of practices on views, such that couples who maintain a traditional division of roles develop more essentialist views as a result, whereas sharing breadwinning and caregiving more equally lead couples to reject essentialist views. Nevertheless, Ross-Plourde et al.’s (2022) longitudinal study showed that men’s pre-natal essentialist perceptions affected their later involvement in baby care through their involvement intentions. More generally, longitudinal studies have documented the effect of parents’ pre-natal/early gender role attitudes on later decisions about work and childcare (Gaunt, 2019; Schober & Scott, 2012; Stertz et al., 2017). It is likely that there are bidirectional influences of essentialism and involvement in childcare, in the same way that women’s early gender role attitudes predict their later work hours, which in turn predict their later gender role attitudes (Corrigall & Konrad, 2007).

The findings from the current study draw on a representative sample of British parents to provide evidence for the key role of biological essentialism and reveal one path through which its effect is mediated. More research is needed to establish the causal relationships between essentialism and childcare as well as the underlying mechanisms in these relationships. Future studies would benefit from an extensive longitudinal examination of mediating and moderating factors. For example, previous findings suggest that the rejection of essentialist beliefs increases men’s parenting self-efficacy (Donithen & Schoppe-Sullivan, 2022) and women’s expectations for an equal division of childcare (Deutsch et al., 2007). A recent gender-binary cycle model (Saguy et al., 2021) proposes gender role attitudes as a mediating variable, suggesting that biological essentialism contributes to a non-egalitarian gender ideology, which leads individuals to conform to a gendered environment, ultimately reinforcing essentialist views. Longitudinal work is needed to illuminate these processes.

Practice Implications

Recent studies indicate widespread public support for gender equality in work and care in younger generations (e.g., Scarborough et al., 2019). In addition, numerous studies attest to the substantial benefits of greater father involvement in childcare for child development, family wellbeing and relationship satisfaction (Diniz et el. 2021; Schober, 2012). Our findings highlight the role of biological essentialism in parents’ involvement in work and childcare and can inform intervention programs designed to enhance fathers’ involvement (Henry et al., 2020; Pruett et al., 2017). Specifically, intervention programs could benefit from addressing parents’ essentialist beliefs as a route to enhance fathers’ self-efficacy and both partners’ expectations of greater sharing. More broadly, gender equal state policies could have a significant impact on public perceptions of men’s and women’s innate abilities to care for children, through both state endorsement of paternal involvement and increased experience that would challenge essentialist beliefs. For example, introducing nontransferable parental leave for fathers would facilitate beliefs in men’s ability to nurture, which in turn could contribute to greater involvement of fathers in childcare from an early age, greater participation of mothers in the labor force, and overall greater gender equality.

Conclusion

This study sheds light on the under-researched role of biological essentialism in parents’ division of work and childcare. Our results attest to the explanatory power of essentialist perceptions, alongside the lack of contribution of gender role attitudes, which challenges previous findings regarding the importance of gender role attitudes for involvement in childcare. We found that each parent’s endorsement of biological essentialism was related to both their own and their partner’s involvement in childcare, and that these associations were mediated by parents’ paid work hours. While more research is needed to establish additional potential mediators and moderators of these effects, the current findings add to the accumulating evidence for the importance of parents’ social-psychological characteristics and outline ways to promote greater gender equality.

References

Aassve, A., Fuochi, G., & Mencarini, L. (2014). Desperate housework: Relative resources, time availability, economic dependency, and gender ideology across Europe. Journal of Family Issues, 35(8), 1000–1022. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x14522248

Altintas, E., & Sullivan, O. (2017). Trends in fathers’ contribution to housework and childcare under different welfare policy regimes. Social Politics: International Studies in Gender State & Society, 24(1), 81–108. https://doi.org/10.1093/sp/jxw007

Andringa, W., Nieuwenhuis, R., & Van Gerven, M. (2015). Women’s working hours: The interplay between gender role attitudes, motherhood, and public childcare support in 23 European countries. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 35(9/10), 582–599. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSSP-10-2014-0073

Becker, G. (1981). A treatise on the family. Harvard University Press.

Bem, S. L. (1993). The lenses of gender: Transforming the debate on sexual inequality. Yale University Press.

Bergen, E. (1991). The economic context of labor allocation: Implications for gender stratification. Journal of Family Issues, 12, 140–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251391012002001

Bianchi, S. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00726.x

Buchanan, T., McFarlane, A., & Das, A. (2016). A counterfactual analysis of the gender gap in parenting time: Explained and unexplained variances at different stages of parenting. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 47(2), 193–219. https://doi.org/10.3138/jcfs.47.2.193

Bulanda, R. E. (2004). Paternal involvement with children: The influence of gender ideologies. Journal of Marriage and Family, 66, 40–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2455.2004.00003.x

Bünning, M. (2020). Paternal part-time employment and fathers’ long‐term involvement in child care and housework. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(2), 566–586. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12608

Carlson, M. J., Pilkauskas, N. V., McLanahan, S. S., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2011). Couples as partners and parents over children’s early years. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73, 317–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00809.x

Corrigall, E. A., & Konrad, A. M. (2007). Gender role attitudes and careers: A longitudinal study. Sex Roles, 56, 847–855. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9242-0

Costa Dias, M., Joyce, R., & Parodi, F. (2020). The gender pay gap in the UK: Children and experience in work. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 36(4), 855–881. https://doi.org/10.1920/wp.ifs.2018.w1802

Coverman, S. (1985). Explaining husbands’ participation in domestic labor. Sociological Quarterly, 26, 81–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.1985.tb00217.x

Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2010). Parenthood, gender and work-family time in USA, Australia, Italy, France and Denmark. Journal of Marriage & Family, 72, 1344–1361. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00769.x

Craig, L., & Mullan, K. (2011). How mothers and fathers share childcare: A cross-national time-use comparison. American Sociological Review, 76(6), 834–861. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122411427673

Daminger, A. (2020). De-gendered processes, gendered outcomes: How egalitarian couples make sense of non-egalitarian household practices. American Sociological Review, 85(5), 806–829. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122420950208

Davis, S. N., & Greenstein, T. N. (2009). Gender ideology: Components, predictors, and consequences. Annual Review of Sociology, 35, 87–105. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-115920

Deutsch, F. M. (1999). Halving it all: How equally shared parenting works. Harvard University Press.

Deutsch, F. M. (2007). Undoing gender. Gender & Society, 21(1), 106–127. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243206293577

Deutsch, F. M., & Gaunt, R. A. (2020). Creating equality at home. How 25 couples around the globe share housework and childcare. Cambridge University Press.

Deutsch, F. M., Lussier, J. B., & Servis, L. J. (1993). Husbands at home: Predictors of paternal participation in childcare and housework. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 1154–1166. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.65.6.1154

Deutsch, F. M., Kokot, A. P., & Binder, K. S. (2007). College women’s plans for different types of egalitarian marriages. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69(4), 916–929. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00421.x

Diniz, E., Brandao, T., Monteiro, L., & Verissimo, M. (2021). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 77–99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12410

Donithen, R., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. (2022). Correlates and predictors of parenting self-efficacy in new fathers. Journal of Family Psychology, 36(3), 396–405. https://doi.org/10.1037/fam0000910

Eurostat (2022). Average number of usual weekly hours of work in main job, by sex, professional status, full-time/part-time and economic activity (from 2008 onwards. NACE Rev 2) [Dataset].

Gaunt, R. (2005). The role of value priorities in paternal and maternal involvement in childcare. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 643–655. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2005.00159.x

Gaunt, R. (2006). Biological essentialism, gender ideologies, and role attitudes: What determines parents’ involvement in childcare. Sex Roles, 55, 223–233. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9105-0

Gaunt, R. (2019). Social psychological predictors of involvement in childcare: The mediating role of changes in women’s work patterns after childbirth. Community Work and Family, 22(2), 183–202. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2018.1428170

Gaunt, R., & Scott, J. (2014). Parents’ involvement in childcare: Do parental and work identities matter? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 38, 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1177/0361684314533484

Gaunt, R., Jordan, A., Tarrant, A., Chanamuto, N., Pinho, M., & Wezyk, A. (2022). Caregiving dads, breadwinning mums: Transforming gender in work and childcare? Nuffield Foundation. https://www.nuffieldfoundation.org/project/caregiving-dads-breadwinning-mums-creating-genderequality-in-the-home

Gershuny, J. (2004). Time, through the life course, in the family. In J. Scott, J. Treas, & M. Richards (Eds.), The Blackwell companion to the sociology of families (pp. 158–173). Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Goldberg, J. S. (2015). Identity and involvement among resident and nonresident fathers. Journal of Family Issues, 36(7), 852–879. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x13500963

Halimi, M., Consuegra, E., Struyven, K., & Engels, N. (2018). A critical examination of the reliability and validity of a gender role attitude scale in Flanders (Belgium): What lessons can be learned? Sex Roles, 78(5), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0807-2

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis. Guilford Press.

Henry, J. B., Julion, W. A., Bounds, D. T., & Sumo, J. N. (2020). Fatherhood matters: An integrative review of fatherhood intervention research. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840519873380

Hook, J. L., & Wolfe, C. M. (2012). New fathers? Residential fathers’ time with children in four countries. Journal of Family Issues, 33, 415–450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X11425779

Horne, R. M., Johnson, M. D., Galambos, N. L., & Krahn, H. J. (2018). Time, money, or gender? Predictors of the division of household labour across life stages. Sex Roles, 78(11), 731–743. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-017-0832-1

Huffman, A. H., Olson, K. J., O’Gara Jr, T. C., & King, E. B. (2014). Gender role beliefs and fathers’ work-family conflict. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 29(7), 774–793. https://doi.org/10.1108/jmp-11-2012-0372

Joshi, M. (2021). I do not want to be a weekend papa: The demographic crisis, active fatherhood, and emergent caring masculinities in Berlin. Journal of Family Issues, 42(5), 883–907. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513x21994154

Kan, M. Y. (2008). Does gender trump money? Housework hours of husbands and wives in Britain. Work Employment and Society, 22(1), 45–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017007087416

Kan, M. Y., Sullivan, O., & Gershuny, J. (2011). Gender convergence in domestic work: Discerning the effects of interactional and institutional barriers from large-scale data. Sociology, 45, 234–251. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038510394014

Kanji, S. (2011). What keeps mothers in full-time employment? European Sociological Review, 27, 509–525. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcq022

Kaplan, D., & Offer, S. (2022). Masculinity ideologies, sensitivity to masculinity threats, and fathers’ involvement in housework and childcare among US employed fathers. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 23(4), 399–411. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000400

Kaufman, G., & Uhlenberg, P. (2000). The influence of parenthood on the work effort of married men and women. Social Forces, 78(3), 931–947. https://doi.org/10.2307/3005936

Kendig, S. M., & Bianchi, S. M. (2008). Single, cohabiting, and married mothers’ time with children. Journal of Marriage and Family, 70, 1228–1240. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2008.00562.x

Khoudja, Y., & Fleischmann, F. (2018). Gender ideology and women’s labor market transitions within couples in the Netherlands. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1087–1106. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12510

Knight, C. R., & Brinton, M. C. (2017). One egalitarianism or several? Two decades of gender-role attitude change in Europe. American Journal of Sociology, 122(5), 1485–1532. https://doi.org/10.1086/689814

Kuo, P. X., Volling, B. L., & Gonzalez, R. (2018). Gender role beliefs, work–family conflict, and father involvement after the birth of a second child. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 19(2), 243–256. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000101

Liss, M., Schiffrin, H. H., Mackintosh, V. H., Miles-McLean, H., & Erchull, M. J. (2013). Development and validation of a quantitative measure of intensive parenting attitudes. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 22(5), 621–636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-012-9616-y

Maineri, A., Lomazzi, V., & Luijkx, R. (2021). Studying the context effect of family norms on gender role attitudes: An experimental design. Survey Research Methods, 15(1), 43–64. https://doi.org/10.18148/srm/2021.v15i1.7656

Mannino, C. A., & Deutsch, F. M. (2007). Changing the division of household labor: A negotiated process between partners. Sex Roles, 56, 309–324. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-006-9181-1

Maume, D. J. (2006). Gender differences in restricting work efforts because of family responsibilities. Journal of Marriage and Family, 68(4), 859–869. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2006.00300.x

Medin, D. L. (1989). Concepts and conceptual structure. American Psychologist, 44, 1469–1481. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.44.12.1469

Norman, H., Elliot, M., & Fagan, C. (2014). Which fathers are the most involved in taking care of their toddlers in the UK? An investigation of the predictors of paternal involvement. Community Work & Family, 17(2), 163–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2013.862361

Offer, S., & Kaplan, D. (2021). The new father between ideals and practices: New masculinity ideology, gender role attitudes, and fathers’ involvement in childcare. Social Problems, 68(4), 986–1009. https://doi.org/10.1093/socpro/spab015

Pailhé, A., Solaz, A., & Stanfors, M. (2021). The great convergence: Gender and unpaid work in Europe and the United States. Population and Development Review, 47(1), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1111/padr.12385

Park, B., Banchefsky, S., & Reynolds, E. B. (2015). Psychological essentialism, gender, and parenthood: Physical transformation leads to heightened essentialist conceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 949–967. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspa0000040

Perry-Jenkins, M., & Gerstel, N. (2020). Work and family in the second decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 420–453. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12636

Petts, R. J., & Knoester, C. (2018). Paternity leave-taking and father engagement. Journal of Marriage and Family, 80(5), 1144–1162. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12494

Pinho, M., & Gaunt, R. (2021). Biological essentialism, gender ideologies, and the division of housework and childcare: Comparing male carer/female breadwinner and traditional families. The Journal of Social Psychology, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2021.1983508

Pinho, M., & Gaunt, R. (2022). Parental and work-related identities among primary caregiving and primary breadwinning mothers and fathers. Families Relationships and Societies, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1332/204674322x16597663169119

Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. (2004). SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behavior Research Methods Instruments & Computers, 36, 717–731. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03206553

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Assessing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42, 185–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273170701341316

Pruett, M. K., Pruett, K., Cowan, C. P., & Cowan, P. A. (2017). Enhancing father involvement in low-income families: A couples group approach to preventive intervention. Child Development, 88(2), 398–407. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12744

Raley, S., Bianchi, S. M., & Wang, W. (2012). When do fathers care? Mothers’ economic contribution and fathers’ involvement in child care. American Journal of Sociology, 117(5), 1422–1459. https://doi.org/10.1086/663354

Risman, B. J. (2009). From doing to undoing: Gender as we know it. Gender & Society, 23(1), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208326874

Ross-Plourde, M., Pierce, T., & de Montigny, F. (2022). Predicting Canadian first-time fathers’ early childcare involvement behaviors using an extended theory of planned behavior. Psychology of Men & Masculinities, 23(1), 13–25. https://doi.org/10.1037/men0000377

Saguy, T., Reifen-Tagar, M., & Joel, D. (2021). The gender-binary cycle: The perpetual relations between a biological-essentialist view of gender, gender ideology, and gender-labelling and sorting. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B, 376(1822), 20200141. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2020.0141

Scarborough, W. J., Sin, R., & Risman, B. (2019). Attitudes and the stalled gender revolution: Egalitarianism, traditionalism, and ambivalence from 1977 through 2016. Gender & Society, 33(2), 173–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243218809604

Schober, P. S. (2012). Paternal childcare and relationship quality: A longitudinal analysis of reciprocal associations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 74, 281–296. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2011.00955.x

Schober, P., & Scott, J. (2012). Maternal employment and gender role attitudes: Dissonance among British men and women in the transition to parenthood. Work Employment & Society, 26(3), 514–530. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012438577

Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J., & Fagan, J. (2020). The evolution of fathering research in the 21st century: Persistent challenges, new directions. Journal of Marriage and Family, 82(1), 175–197. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12645

Shafer, K., Petts, R. J., & Scheibling, C. (2021). Variation in masculinities and fathering behaviors: A cross-national comparison of the United States and Canada. Sex Roles, 84(7), 439–453. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01177-3

Stertz, A. M., Grether, T., & Wiese, B. S. (2017). Gender-role attitudes and parental work decisions after childbirth: A longitudinal dyadic perspective with dual-earner couples. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 101, 104–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.05.005

Sullivan, O., Gershuny, J., & Robinson, J. P. (2018). Stalled or uneven gender revolution? A long-term processual framework for understanding why change is slow. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 263–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12248

Thorsteinsen, K., Parks-Stamm, E. J., Kvalø, M., Olsen, M., & Martiny, S. E. (2022). Mothers’ domestic responsibilities and well-being during the COVID-19 lockdown: The moderating role of gender essentialist beliefs about parenthood. Sex Roles, 87(1–2), 85–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-022-01307-z

Walter, J. G. (2018). The adequacy of measures of gender roles attitudes: A review of current measures in omnibus surveys. Quality & Quantity, 52(2), 829–848. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0491-x

Wang, I. Y., & Cheung, R. Y. (2023). Parents’ gender role attitudes and child adjustment: The mediating role of parental involvement. Sex Roles, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-023-01386-6

West, C., & Zimmerman, D. H. (1987). Doing gender. Gender & Society, 1, 125–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243287001002002

Yavorsky, J. E., Dush, K., C. M., & Schoppe-Sullivan, S. J. (2015). The production of inequality: The gender division of labor across the transition to parenthood. Journal of Marriage and Family, 77(3), 662–679. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12189

Yeung, J. W., Sandberg, J. F., Davis-Kean, P. E., & Hofferth, S. L. (2001). Children’s time with fathers in intact families. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63, 136–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2001.00136.x

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

The study was funded by the Nuffield Foundation, grant #43,623 awarded to the first author. The views expressed are those of the authors and not necessarily the Foundation. Visit www.nuffieldfoundation.org.

The research adhered to the ethical guidelines of the British Psychological Society and the American Psychological Association. Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Lincoln Research Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the study. The participants provided informed consent before participating and confidentiality was strictly maintained.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Gaunt, R., Deutsch, F.M. Mother’s Instinct? Biological Essentialism and Parents’ Involvement in Work and Childcare. Sex Roles 90, 267–279 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-024-01451-8

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-024-01451-8