(Cross-posted at FacilitatedCommunication.org).

The most helpful comments we receive on this blog are ones that point us to specific articles that we haven’t yet reviewed here and may not be aware of—and that may be of possible relevance to FC.

Last week a reader, commenting on this post, suggested that we “familiarize [ourselves] with some of the most recent research regarding developmental dyspraxia (what some folks refer to as apraxia) in autism to understand the unique motor challenges in autism.” This commenter, who characterized herself as “a PT who has a PhD with the focus on differentially [sic] brain connectivity in autism,” referred us to three articles: Dziuk et al. (2007); Mostofky et al. (2011); and Torres et al. (2013). These articles are not currently included on our website, and so I went and read them a few days ago. In this post, I’ll discuss each one in terms of its connections to claims made in support of FC.

With the first, Dziuk et al. (2007), it’s hard to find any connections. The study is of high-functioning individuals with autism—not the population typically subjected to FC or its variants. The focus is on “skilled gestures”; not pointing. Nor are any of its results surprising: complex motor skills are a common—though not universal—challenge for individuals with autism, including in the high-functioning range.

Mostofky et al. (2011), though more recent, is somewhat out of date: it harks back to the time when everyone thought that defective “mirror neurons” were what underlies core autism symptomology. That didn’t pan out. Another of its culprits, however, has so far withstood the test of time: neuronal under-connectivity, specifically between distant brain regions. The thrust of Mostofky et al. is that children with autism have difficulty, as a result of these factors, not just with skilled motor gestures, but with forming what the authors call “action models,” or “sensory-motor programs that form the brain basis for a wide range of skilled behavior and for understanding others’ actions.” The authors propose that impaired action models result in both complex motor deficits and social deficits. The connection between “action models” and social deficits, however, is unconvincing. Social phenomena are not reducible to the sensory-motor phenomena captured by “action models”; social phenomena have much more to do with facial expressions, language, tones of voice, and interactions.

Mostofksy et al.’s most interesting finding is that individuals with autism, when learning how to execute complex gestures, rely more on proprioceptive feedback (that internal sense of where your body is in space) than on visual feedback. However, the authors make no reference to anything related to FC: not to non-speaking/minimally speaking autism; not to language skills; and not to pointing.

Finally, there’s Torres et al. (2013). The first red flag appears in the introduction: the familiar, FC-friendly claim that autistic individuals lack intentional control:

In autism… typical volitional control is highly compromised often with a striking disconnect between the intentions and the actions of the affected individual.

Torres et al. back this up with one citation: a paper co-authored by FC-proponent Anne Donnellan (Robledo et al. 2012), whose “data” consists only of anecdotal accounts, including some from FCed individuals, along with some claims made by Douglas Biklen, the person who introduced FC to the U.S.

In their own paper, however, Torres et al. mostly eschew anecdotes for high-tech equipment, dazzling us with neurological and kinesthetic terminology, brain diagrams, and graphs. The gist is (1) that the consistent and nonrandom movements that typically constitute the goal-directed behaviors (e.g., reaching and pointing) of typically developing individuals over the age of 4 provide sensory feedback to those individuals about those movements and their associated goals; (2) that this results in reliable expectations about other movements and associated goals (“kinesthetic priors”); (3) that these kinesthetic priors help individuals ascribe intent to movement in general—including that of other people; and (4) that autistic movements persist, beyond the age of 4, in being random enough to impede the acquisition of those “kinesthetic priors.”

And then they take this a few steps further:

We propose the hypothesis that the typical development of ‘kinesthetic priors’ is essential not only for anchoring kinesthetic sensing but also for the typical development of… circuits crucial for flexible hierarchical action planning, shifts of attention, and establishing counterfactuals in symbolic problem solving.

Counterfactual problem solving? Who knew that excessive randomness in movement could lead to difficulties answering questions like “If we had left two hours earlier, what time would we have gotten there?”

To say the least, Torres et al. is a highly speculative paper: the hedge “likely” appears 10 times. Among what’s likely, apparently, is that deficient “kinesthetic priors” could also be the causes of all the core deficits of autism: both the social deficits (specifically, recognizing facial expressions and passing Theory of Mind tests), and the restrictive, repetitive behaviors. In other words, the excessive randomness of movement that supposedly characterizes autism is the essence of autism: autism is a movement disorder—just as FC-proponents have said all along.

But even assuming that all its speculations are true, there are a number of problems with Torres et al. as a pro-FC piece.

First, typical 3-4 year olds, the authors find, have non-random movement profiles similar to those with autism. But typical 3-4 year olds have neither the social deficits nor the restrictive/repetitive behaviors of autism. Neither, incidentally, do those with severe movement deficits like cerebral palsy.

Second, their autistic subjects were both verbal and non-verbal, and yet all exhibited similar randomness of movement: “all fall along the statistical region of the TD [typically developing] 3-4 years old.” So, even though Torres et al. suggest that issues with randomness might also affect speech, it’s unclear why it would affect the speech of some but not others.

Third (as I discuss in this post), many autistic kids can detect simple intent and readily ascribe some types of intent to people and other agents.

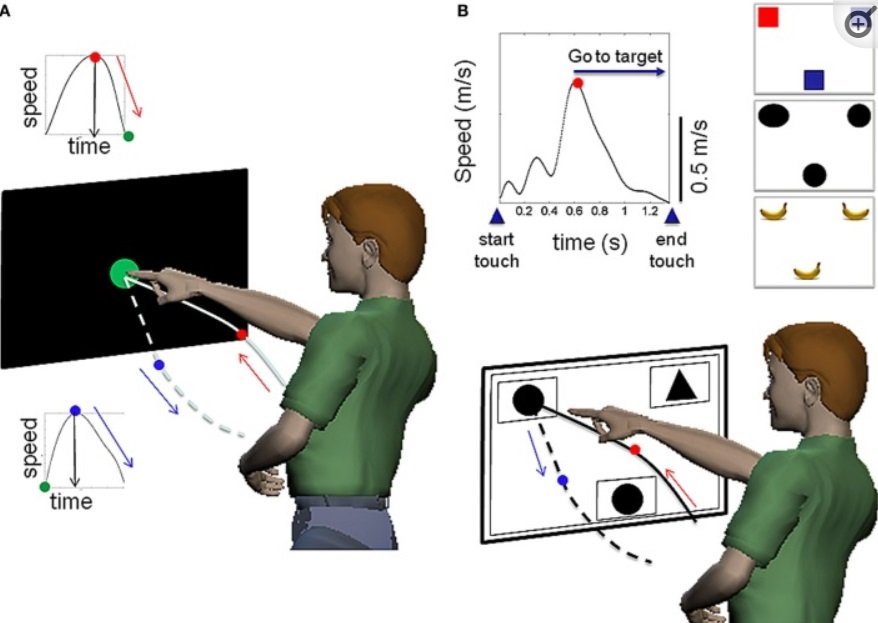

Finally, all of Torres et al.’s subjects can point. Indeed, the focus of their study is on pointing gestures, and even those pointing gestures that involved random movements were frequently accurate (e.g., when individuals were asked to pick out a particular shape from a set of 3: “individuals with ASD often had high accuracy in the match-to-sample decision.” This, of course, undermines one of the usual excuses in S2C and for held-up letterboards: individuals with autism, supposedly, have so much difficulty with fine motor skills like pointing that they need to learn from the S2C practitioners how to “point with their arms” in order to pick out specific letters.

From Torres et al. (2013).

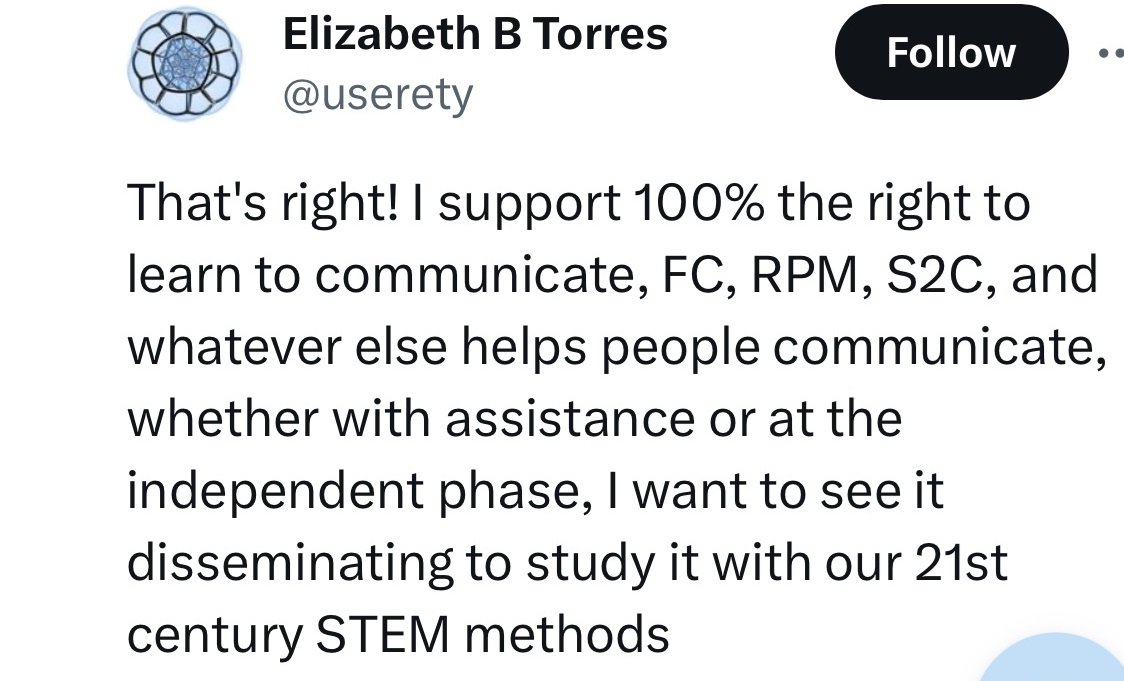

Nonetheless, the lead author in this study, Elizabeth Torres, outed herself on Twitter last February as an enthusiastic supporter of FC and all its variants:

(Here we see the qualified “don’t test” slogan of today’s FC proponents: it’s ok to study FC with “21st century STEM” methods. But it’s not OK to test FC with simple 20th century message-passing tools that would directly answer questions about authorship, including in so-called “independent” typers who can only type spontaneous messages with helpers within auditory or visual cueing range.)

But back to the three articles—all of which focus on movement. Trivially, of course, all observable behavior amounts to movement, and so you could potentially explain everything, from bipolar disorder to trouble producing answers to calculus problems, as a movement disorder. But that would be even more reductionist than Mostofsky’s attempts to reduce social phenomena to “action models.”

Beyond this, there are a few additional problems.

First, none of these three accounts acknowledge the existence of the many autistic individuals, including non-speakers, who exhibit no obvious motor skills difficulties: the minimally speaking 4-year-old who smoothly switches LPs on a record player; the severely autistic 6-year-old who walks like a gymnast, perfectly balanced, along a narrow railing; the non-speaking 10-year-old who can unlock a refrigerator lock, fill a tall glass to the rim with chocolate milk, and move the glass to his lips without spilling. (Or is someone going to claim that these actions are not under volitional control?) For the motor/apraxia account to explain the core symptoms, it would have to be universal.

More importantly, none of these motor accounts explain away the much earlier emerging social attention deficits that characterize autism: that is, the lack of attention to social stimuli in infants as young as 2-6 months old who are later diagnosed as autistic. Brain imaging studies have found that the brains of infants at risk for autism (many of them later diagnosed) show less selective attention to social stimuli (Blanco et al., 2023; Lloyd-Fox et al. 2013); these patterns play out, in turn, in diminished social looking and diminished eye gaze monitoring (Jones et al., 2016; Chawarska et al., 2013; Jones & Klin, 2013; Mastro et al., 2002).

This diminished social attention, in turn, persists into the later years of childhood (See, e.g., Dawson et al., 1998). And as I discussed in my earlier post, it reduces the opportunity to acquire language; indeed, just how diminished a child’s social attention is correlates with just how limited his or her acquired language is.

While difficulties with complex motor movements may overlap with autism and further aggravate opportunities for social learning, they do not explain away the diminished social attention in 4-6-month-olds. Nor do they explain away the need by minimally-speaking individuals, when they point to letters, for physical touch, held-up letterboards, or hovering prompters who bark out “Keep going,” “What makes sense?” and “Right next door!”

REFERENCES:

Blanco, B., Lloyd-Fox, S., Begum-Ali, J., Pirazzoli, L., Goodwin, A., Mason, L., Pasco, G., Charman, T., Jones, E. J. H., Johnson, M. H., & BASIS/STAARS Team (2023). Cortical responses to social stimuli in infants at elevated likelihood of ASD and/or ADHD: A prospective cross-condition fNIRS study. Cortex; a journal devoted to the study of the nervous system and behavior, 169, 18–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2023.07.010

Chawarska, K., Macari, S., & Shic, F. (2013). Decreased spontaneous attention to social scenes in 6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism spectrum disorders. Biological psychiatry, 74(3), 195–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2012.11.022

Dawson, G., Meltzoff, A. N., Osterling, J., Rinaldi, J., & Brown, E. (1998). Children with autism fail to orient to naturally occurring social stimuli. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 28(6), 479–485. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1026043926488

Dziuk, M. A., Gidley Larson, J. C., Apostu, A., Mahone, E. M., Denckla, M. B., & Mostofsky, S. H. (2007). Dyspraxia in autism: association with motor, social, and communicative deficits. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 49(10), 734–739. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8749.2007.00734.x

Jones, E. J., Venema, K., Earl, R., Lowy, R., Barnes, K., Estes, A., Dawson, G., & Webb, S. J. (2016). Reduced engagement with social stimuli in 6-month-old infants with later autism spectrum disorder: a longitudinal prospective study of infants at high familial risk. Journal of neurodevelopmental disorders, 8, 7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11689-016-9139-8

Jones, W., & Klin, A. (2013). Attention to eyes is present but in decline in 2-6-month-old infants later diagnosed with autism. Nature, 504(7480), 427–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature12715

Lloyd-Fox, S., Blasi, A., Elwell, C. E., Charman, T., Murphy, D., & Johnson, M. H. (2013). Reduced neural sensitivity to social stimuli in infants at risk for autism. Proceedings. Biological sciences, 280(1758), 20123026. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2012.3026

Maestro, S., Muratori, F., Cavallaro, M. C., Pei, F., Stern, D., Golse, B., & Palacio-Espasa, F. (2002). Attentional skills during the first 6 months of age in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 41(10), 1239–1245. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200210000-00014

Mostofsky, S. H., & Ewen, J. B. (2011). Altered connectivity and action model formation in autism is autism. The Neuroscientist : a review journal bringing neurobiology, neurology and psychiatry, 17(4), 437–448. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073858410392381

Robledo, J., Donnellan, A. M., and Strandt-Conroy, K. (2012). An exploration of sensory and movement differences from the perspective of individuals with autism. Front. Integr. Neurosci. 6:107. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2012.00107

Torres, E. B., Brincker, M., Isenhower, R. W., Yanovich, P., Stigler, K. A., Nurnberger, J. I., Metaxas, D. N., & José, J. V. (2013). Autism: the micro-movement perspective. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience, 7, 32. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnint.2013.00032