When one knew that any document was due for destruction, or even when one saw a scrap of waste paper lying about, it was an automatic action to lift the flap of the nearest memory hole and drop it in, whereupon it would be whirled away on a current of warm air to the enormous furnaces which were hidden somewhere in the recesses of the building.

-George Orwell, 1984

This piece was made possible by the Center for Educator Wellness and Learning. Click here to read the whole piece for free on their website.

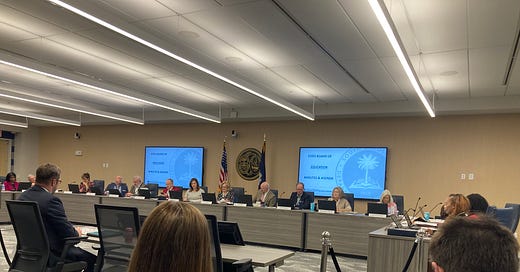

Recently, the South Carolina State Board of Education saw a sudden shift in its approach to banning books. (Both Superintendent Ellen Weaver and Board member Cheryl Collier— echoing national talking points from Moms for Liberty— have publicly claimed removing a book from every school in the state is not actually book banning, because, they argue, copies of the books still exist even if many SC students can’t access them). For the first time, several members of the Board spoke out against the process, created by State Board Regulation 43-170, of challenging and removing books.

Current Laurens 56 Superintendent Dr. David O’Shields and associate pastor Rev. Tony Vincent, in particular, struck a tone of alarm at how much control the State Board had (intentionally or not) given over the state’s library and classroom book collections to one person from Beaufort County.

But why do book bans matter, anyway?

As someone who spends a great deal of time in State Board meetings and Instructional Materials Review Committee meetings (where committee members generally hear and act on advice from department attorney Robert Cathcart on whether or not to remove books-- usually voting without any discussion) listening to folks argue back and forth about which books children should be able to access, I have asked myself this question a lot. There are, after all, arguably much bigger problems facing the world, America, South Carolina, and public schools.

I think Rev. Vincent most powerfully addressed one of the main reasons book bans matter when he said, during that most recent State Board of Education meeting,

We’ve heard, time and again, personal stories of how those books spoke to the lived experiences of young people. How they helped them better understand their lives… Having easy access— in school libraries, not through Amazon or harder measures— having access to these books, I think, could possibly save lives…”

And while I can understand that the idea of books saving lives seems hopelessly hyperbolic to many people, the research-- along with, as Vincent pointed out, hours of testimony from students, parents, and experts in abuse and child psychology who have attended the Board meetings since this regulation was first introduced-- bears out the impact of giving all student representation in instructional materials.

For example, research from organizations like the Trevor Project has supported the idea that making students feel included saves lives: “LGBTQ+ young people who reported living in very accepting communities attempted suicide at less than half the rate of those who reported living in very unaccepting communities.”

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Other Duties (as assigned) to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.