Why Intelligent Design Fails: A Scientific Critique of the New Creationism will soon be out in paperback!

I was honored to contribute a chapter (co-written with Wesley Elsberry) to this book, which also features chapters by Taner Edis, Matt Young, Gert Korthof, David Ussery, Ian Musgrave, Alan Gishlick, Niall Shanks, Istvan Karsai, Gary Hurd, Mark Perakh, and Victor Stenger. The book's editors were Matt Young and Taner Edis, and it was published by Rutgers University Press. (For more information about the book, see here.) I was pleased to see that it sold much better than expected (but alas, I don't get any royalties) --- so well that Rutgers has decided to release a paperback version.

This version sells for only US $24.95, and you can order it at amazon. Buy a copy, and donate it to your local public library!

Postscript: I just learned that an even better deal is available from the Rutgers University Press website: you can get a copy for just $19.96.

Sunday, February 19, 2006

Thursday, February 16, 2006

Courses Have Consequences

John Tibbits, president of our local community college, Conestoga College, is all upset because McMaster's new satellite medical school will go in a new downtown Kitchener campus of the University of Waterloo, and not at Conestoga. In an article in our local paper, the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, he suggested the decision was not "rational" or "logical".

Is it possible that Conestoga didn't get the new medical school because they have a history of offering courses that endorse quack therapies, such as HOLI8170 (Reflexology) and HOLI8120 (Therapeutic Touch)? Or because they have a history of offering courses that tout pseudoscience, such as META0110 (Psychic World), META0130 (Advanced Psychic World), and META0060 (Reincarnation - Who Were You?)?

I'm sure many of Conestoga College's courses are not as wacky as these, and most are probably very helpful to the people who take them. But courses have consequences. If your curriculum contains nutball entries, and you offer them year after year even after people have complained, don't be surprised if some legitimate scientists and physicians don't want to be associated with you.

Is it possible that Conestoga didn't get the new medical school because they have a history of offering courses that endorse quack therapies, such as HOLI8170 (Reflexology) and HOLI8120 (Therapeutic Touch)? Or because they have a history of offering courses that tout pseudoscience, such as META0110 (Psychic World), META0130 (Advanced Psychic World), and META0060 (Reincarnation - Who Were You?)?

I'm sure many of Conestoga College's courses are not as wacky as these, and most are probably very helpful to the people who take them. But courses have consequences. If your curriculum contains nutball entries, and you offer them year after year even after people have complained, don't be surprised if some legitimate scientists and physicians don't want to be associated with you.

Monday, February 13, 2006

Does the God of the Bible Exist? - A Debate Report

I attended the February 11 debate sponsored by the Kitchener-Waterloo-Cambridge-Guelph Humanists. It was entitled "Does the God of the Bible Exist?" and featured Chris diCarlo of the University of Ontario Institute of Technology versus Scott Wilkinson, pastor of the New Creation Reformed Presbyterian Church.

The debate was held as a "Darwin Day" feature which, to my mind, was an unfortunate choice because of the implication that evolutionary biology is for atheists only. Here is my report on the debate, with my own rebuttals in italics and red.

Pastor Wilkinson started the debate by disputing the definition of "faith" as "belief in the absence of evidence". He said that the bible says that faith is knowledge based on reason, on evidence. Next, he disputed the view that scientific evidence is the only legitimate evidence. Many things, he said, are known and proven, but not based on science. Four of them are the existence of numbers, the laws of logic, morality, and personal self-consciousness. He stated that the belief in naturalism is not based on evidence and claimed that scientific knowledge is actually based on men. Is science based on evidence you personally have seen and tested? he asked. He quoted Guth to the effect that scientific phenomena are not directly observed.

He then claimed that the Christian god is an objective reality which is empirically provable, and unbelief is inexcusable. The Christian world view is true because its negation is impossible. He presented an argument which he called the "transcendental argument": the laws of logic are necessary for all rational argument. Therefore, you must maintain that the laws of logic are real and invariant. But in a materialist world there cannot be laws of logic because logic would be contingent and not universal.

Next, he claimed that materialists have a problem with induction. They observe phenomena and deduce rules, but this assumes the uniformity of nature (future will be like the past), and there is no logical justification for induction.

Finally, he said that in a materialist worldview, there is no objective view of right and wrong.

I thought many of these points were very weak. While it is true that some Platonic philosophers maintain that numbers have an independent existence, this is not agreed to by all philosophers, and it's certainly not "known and proven" as Wilkinson asserted.

It's true that we often use "laws of logic" when we argue. For example, when one reasons about mathematical objects, one uses rules such as "either the proposition A holds, or its negation holds". But, in fact, we don't have any guarantee that this kind of reasoning will never lead to absurdities such as 1 = 0. For Gödel proved that any sufficiently powerful mathematical system is either inconsistent or incomplete, and furthermore we can't carry out a proof of consistency within that system. (We might be able to in some more powerful system.) I think most mathematicians believe that mathematics is consistent but incomplete, but we don't actually know for sure. It could well be that the "laws of logic" lead us to unresolvable contradictions.

Wilkinson referred repeatedly to the "laws of logic" as if these have some independent existence. But it seems likely to me that the mathematical rules we think of as "laws of logic" are just models of physical existence, and those models may not accurately reflect the complexities of the world. For example, consider the propostion "electron e is at position p at time t". Can this really be said to have a single truth value, true or false? Or how about the proposition "Mary is a good person"? Maybe Mary pays her taxes, but once beat her husband. Can she really be said to be either "good" or "not good"? Furthermore, mathematicians have explored other kinds of logics, such as multi-valued logic, and fuzzy logic, and so I don't think there is one set of "laws of logic" agreed on by all people. After all, the continuum hypothesis is independent of set theory, so we can, according to our preference, choose it to be either true or false.

My view of the "laws of logic" are that they are a useful abstraction that has often proved reliable in the past in many situations. But they don't need to be elevated to "universal" or "immutable" in order to be useful, and we need to recognize their limitations.

I also don't see any problem with the fact that induction can't be justified through logic alone. Why should this trouble us? Most of our knowledge is empirical, not derived through logic. In the absence of other evidence, rough uniformity of the future against the past seems like an entirely reasonable assumption.

Wilkinson seems unaware that morality can be investigated through the scientific method. As for "personal self-consciousness", Wilkinson seems unaware of the work of Gordon Gallup, who devised a scientific test for animal self-consciousness.

Finally, I strongly dispute the characterization of science as "based on men". Yes, it is true that I have not personally performed experiments in subatomic physics that verify the existence (say) of positrons. But anyone with a university or even high-school science education will, in fact, have performed many experiments verifying many aspects of science. The thing that makes science different from religion is that its conclusions are, in principle, verifiable by everyone with enough interest and time. And furthermore, science is self-correcting in a way that religion is not. Really fundamental results are verified over and over by different teams, each with a strong incentive to prove the other guys wrong. The history of science shows this self-correcting aspect clearly (consider the case of N-rays).

Chris diCarlo spoke next. He said his presentation would be divided into four parts:

1. He said he was an "agtheist", that is, someone who is atheistic towards all known religions, but agnostic on the question of whether the universe itself came into being through an intentional act. As for what can be known about god, he pointed to the paradox that the more you say about god's attributes (omniscience, omnibenevolence, etc.) the more inconsistencies develop. His view is that god was fashioned by people to provide (a) an explanation of causality in nature (b) a guide for moral behavior and (c) the illusion of immortality.

2. He argued that we evaluate whether something constitutes "knowledge" based on criteria such as consistency, coherence, simplicity and reliability.

At this point Prof. diCarlo's time was up, so he saved points 3 and 4 for later, and the cross examination began.

Prof. diCarlo asked Pastor Wilkinson, "How old do you think the universe is?" Wilkinson replied that he agreed with everything in the bible, and based on the biblical account, the universe is 6000-10000 years old. Wilkinson argued that the scientific view of the age of the earth is based on naturalism and the uniformity of nature (radioactive decay rates are unchanged). But the very existence of logic and the scientific method assumes god exists and endowed nature with uniform laws, so this argument is self-defeating for the materialist. He quoted Patricia Churchill (I think he meant "Churchland") as saying that reason has developed only because it has survival benefit. Thus, in the evolutionary view, logic is geared towards survival and not truth claims. Atheists support abortion, homosexuality, and euthanasia.

The scientific method certainly does not assume that god exists; it is completely silent on the question. We date the earth as 4.6 billion years old not because we assume that decay constants are really constant, but because we have good reason to think so: experiments were done early in the history of radioactivity to try to influence decay rates through explosions, changes of temperature and pressure, inducing strong magnetic fields, etc., but only very small changes were observed. See Dalrymple's book, The Age of the Earth. So I think it is dishonest of Wilkinson to maintain that decay rates are unchanged is merely an assumption.

In any event, it is Wilkinson who is maintaining that the uniformity of nature is only explicable to the theist, so as a theist, he should be more convinced by uniformitarian arguments than the atheist. Thus, his argument is self-defeating.

The second part of his claim is a reworked version of Plantinga's argument against evolution: evolution only endows us with reason enough to reproduce efficiently. But then we have no reason to trust our mental faculties that came up with the theory of evolution. I find this argument silly, because it assumes a certain black-and-white view of our mental faculties: either they are entirely reliable, or they are not to be trusted at all. No one who has read history can believe that man is never capable of folly; the whole history of the world is the history of folly. And yet an evolutionary development that gave us an entirely bogus picture of the world would not likely ensure survival. So I think we can provisionally trust in our reason, but always be alert to the ways it may deceive us.

Prof. diCarlo spoke again. He said it was epistemically irresponsible to believe in the Christian god, since the evidence we have is not sufficient for the claim. He went on to his point 4:

4. The inherent tension in belief of the god of the bible: (a) the tension between an all-powerful, all-knowing god, and human free will (b) specifying one particular god among an indefinite choice is divisive and leads to conflicts (c) the tension between human biology and the doctrines of Christianity, e.g., masturbation and (d) the problem of evil. (He put up a slide with a picture of the tablet that would normally have the 10 commandments on it, but instead had "Thou shalt not masturbate". This was pretty funny, especially because when it was Pastor Wilkinson's turn to speak, the slide stayed up behind him.)

Pastor Wilkinson spoke again. In the materialist world view, he claimed, there was no objective standard of morality, or right and wrong. No god implies no morality. Hitler based his world view on Darwin's view of natural selection. If the materialist world view is correct, there is nothing wrong with Hitler's murders. Evolutionary biologists agree that the theory of evolution arose because people want to get away from traditional sexual morality (he quoted Huxley).

Next, there was some final cross-examination. Prof. diCarlo got Wilkinson to admit that God hates all believers in other religions except Wilkinson's brand of Christianity. In particular, Wilkinson explicitly stated that God hates Muslims! Now that was a rather explosive claim, but entirely missing from the Record's account of the debate by religion reporter Mirko Petricevic. I have observed that Petricevic constantly slants his coverage to favor the religious point of view, and this is just another data point.

Prof. diCarlo also made some effective points about the incompatibility of the Christian god with human free will. The Christian god's view of us is the same way: since his is omniscient and created the universe, he already knew 14 billion years ago whether we would be saved or not. We can do nothing to defeat his knowledge and so don't have free will. He made an analogy with the movie "Jaws": you can watch it as many times as you like, but the shark always dies at the end. God watching history unfold is the same. Pastor Wilkinson had no good response to this argument.

In his closing remarks, Pastor Wilkinson made the point that only Christianity, among all religions, must be true because in no other religion is there justice. In particular, Islam does not provide justice for evil deeds during life. But I felt he contradicted himself, since he made two claims: Christianity provides justice, but one can also be saved if one repents on one's deathbed. In other words, Hitler could be in heaven if he repented and asked god's forgiveness at the last moment. So how is that justice?

At this point the debate ended, and I will now give some comments without resorting to red and italics.

First, both speakers had polished presentations. Pastor Wilkinson's closing remarks, in particular, were an earnest sermon about man's need for Christianity, and they were well-received by many of the believers in the crowd. Prof. diCarlo's brand of sardonic humor succeeded in making many points, particularly about Wilkinson's condemning Jews, homosexuals, and Muslims to hell.

On the other hand, both speakers could have addressed the other's arguments in more detail. It was almost as if we had two parallel presentations which, despite the opportunity for cross-examination, didn't interact all that much. Prof. diCarlo, for example, never really addressed Pastor Wilkinson's point about the "laws of logic", which was really his main argument. Also, while I admired his wit and intellect, I felt Prof. diCarlo sometimes came across as a little too flippant and arrogant. It sometimes seemed like he treated the audience as a philosophy class where he was the instructor.

After the debate, I asked Pastor Wilkinson the following question: "You say the earth is 10,000 years old. Yet there are ice cores in Antarctica that give an unbroken record of 190,000 years. How do you explain this?" He had no good answer, mumbling about "uniformity" and "assumptions". But the ice core record we have agrees with data in the recent past, and there is no reason to believe it does not actually represent a record of history. When pressed, he suggested a comet might have exploded in the atmosphere and just happened to put down a series of layers that exactly correspond to our historical record. But, of course, this is just pure fantasy. Where is the evidence for this comet? How did it happen to put down a series of layers that exactly matches our historical records? I made the point to him that no thinking person is going to subscribe to Wilkinson's version of Christianity if it causes him to deny the evidence of his own senses.

For me it was an entertaining evening, but probably not one that changed many minds.

The debate was held as a "Darwin Day" feature which, to my mind, was an unfortunate choice because of the implication that evolutionary biology is for atheists only. Here is my report on the debate, with my own rebuttals in italics and red.

Pastor Wilkinson started the debate by disputing the definition of "faith" as "belief in the absence of evidence". He said that the bible says that faith is knowledge based on reason, on evidence. Next, he disputed the view that scientific evidence is the only legitimate evidence. Many things, he said, are known and proven, but not based on science. Four of them are the existence of numbers, the laws of logic, morality, and personal self-consciousness. He stated that the belief in naturalism is not based on evidence and claimed that scientific knowledge is actually based on men. Is science based on evidence you personally have seen and tested? he asked. He quoted Guth to the effect that scientific phenomena are not directly observed.

He then claimed that the Christian god is an objective reality which is empirically provable, and unbelief is inexcusable. The Christian world view is true because its negation is impossible. He presented an argument which he called the "transcendental argument": the laws of logic are necessary for all rational argument. Therefore, you must maintain that the laws of logic are real and invariant. But in a materialist world there cannot be laws of logic because logic would be contingent and not universal.

Next, he claimed that materialists have a problem with induction. They observe phenomena and deduce rules, but this assumes the uniformity of nature (future will be like the past), and there is no logical justification for induction.

Finally, he said that in a materialist worldview, there is no objective view of right and wrong.

I thought many of these points were very weak. While it is true that some Platonic philosophers maintain that numbers have an independent existence, this is not agreed to by all philosophers, and it's certainly not "known and proven" as Wilkinson asserted.

It's true that we often use "laws of logic" when we argue. For example, when one reasons about mathematical objects, one uses rules such as "either the proposition A holds, or its negation holds". But, in fact, we don't have any guarantee that this kind of reasoning will never lead to absurdities such as 1 = 0. For Gödel proved that any sufficiently powerful mathematical system is either inconsistent or incomplete, and furthermore we can't carry out a proof of consistency within that system. (We might be able to in some more powerful system.) I think most mathematicians believe that mathematics is consistent but incomplete, but we don't actually know for sure. It could well be that the "laws of logic" lead us to unresolvable contradictions.

Wilkinson referred repeatedly to the "laws of logic" as if these have some independent existence. But it seems likely to me that the mathematical rules we think of as "laws of logic" are just models of physical existence, and those models may not accurately reflect the complexities of the world. For example, consider the propostion "electron e is at position p at time t". Can this really be said to have a single truth value, true or false? Or how about the proposition "Mary is a good person"? Maybe Mary pays her taxes, but once beat her husband. Can she really be said to be either "good" or "not good"? Furthermore, mathematicians have explored other kinds of logics, such as multi-valued logic, and fuzzy logic, and so I don't think there is one set of "laws of logic" agreed on by all people. After all, the continuum hypothesis is independent of set theory, so we can, according to our preference, choose it to be either true or false.

My view of the "laws of logic" are that they are a useful abstraction that has often proved reliable in the past in many situations. But they don't need to be elevated to "universal" or "immutable" in order to be useful, and we need to recognize their limitations.

I also don't see any problem with the fact that induction can't be justified through logic alone. Why should this trouble us? Most of our knowledge is empirical, not derived through logic. In the absence of other evidence, rough uniformity of the future against the past seems like an entirely reasonable assumption.

Wilkinson seems unaware that morality can be investigated through the scientific method. As for "personal self-consciousness", Wilkinson seems unaware of the work of Gordon Gallup, who devised a scientific test for animal self-consciousness.

Finally, I strongly dispute the characterization of science as "based on men". Yes, it is true that I have not personally performed experiments in subatomic physics that verify the existence (say) of positrons. But anyone with a university or even high-school science education will, in fact, have performed many experiments verifying many aspects of science. The thing that makes science different from religion is that its conclusions are, in principle, verifiable by everyone with enough interest and time. And furthermore, science is self-correcting in a way that religion is not. Really fundamental results are verified over and over by different teams, each with a strong incentive to prove the other guys wrong. The history of science shows this self-correcting aspect clearly (consider the case of N-rays).

Chris diCarlo spoke next. He said his presentation would be divided into four parts:

- What can be known about God?

- Such beliefs fall short of what we call "knowledge".

- It is epistemically irresponsible to believe in a universe specially created by the Christian god.

- Gods are no more real than the Easter Bunny or Santa Claus.

1. He said he was an "agtheist", that is, someone who is atheistic towards all known religions, but agnostic on the question of whether the universe itself came into being through an intentional act. As for what can be known about god, he pointed to the paradox that the more you say about god's attributes (omniscience, omnibenevolence, etc.) the more inconsistencies develop. His view is that god was fashioned by people to provide (a) an explanation of causality in nature (b) a guide for moral behavior and (c) the illusion of immortality.

2. He argued that we evaluate whether something constitutes "knowledge" based on criteria such as consistency, coherence, simplicity and reliability.

At this point Prof. diCarlo's time was up, so he saved points 3 and 4 for later, and the cross examination began.

Prof. diCarlo asked Pastor Wilkinson, "How old do you think the universe is?" Wilkinson replied that he agreed with everything in the bible, and based on the biblical account, the universe is 6000-10000 years old. Wilkinson argued that the scientific view of the age of the earth is based on naturalism and the uniformity of nature (radioactive decay rates are unchanged). But the very existence of logic and the scientific method assumes god exists and endowed nature with uniform laws, so this argument is self-defeating for the materialist. He quoted Patricia Churchill (I think he meant "Churchland") as saying that reason has developed only because it has survival benefit. Thus, in the evolutionary view, logic is geared towards survival and not truth claims. Atheists support abortion, homosexuality, and euthanasia.

The scientific method certainly does not assume that god exists; it is completely silent on the question. We date the earth as 4.6 billion years old not because we assume that decay constants are really constant, but because we have good reason to think so: experiments were done early in the history of radioactivity to try to influence decay rates through explosions, changes of temperature and pressure, inducing strong magnetic fields, etc., but only very small changes were observed. See Dalrymple's book, The Age of the Earth. So I think it is dishonest of Wilkinson to maintain that decay rates are unchanged is merely an assumption.

In any event, it is Wilkinson who is maintaining that the uniformity of nature is only explicable to the theist, so as a theist, he should be more convinced by uniformitarian arguments than the atheist. Thus, his argument is self-defeating.

The second part of his claim is a reworked version of Plantinga's argument against evolution: evolution only endows us with reason enough to reproduce efficiently. But then we have no reason to trust our mental faculties that came up with the theory of evolution. I find this argument silly, because it assumes a certain black-and-white view of our mental faculties: either they are entirely reliable, or they are not to be trusted at all. No one who has read history can believe that man is never capable of folly; the whole history of the world is the history of folly. And yet an evolutionary development that gave us an entirely bogus picture of the world would not likely ensure survival. So I think we can provisionally trust in our reason, but always be alert to the ways it may deceive us.

Prof. diCarlo spoke again. He said it was epistemically irresponsible to believe in the Christian god, since the evidence we have is not sufficient for the claim. He went on to his point 4:

4. The inherent tension in belief of the god of the bible: (a) the tension between an all-powerful, all-knowing god, and human free will (b) specifying one particular god among an indefinite choice is divisive and leads to conflicts (c) the tension between human biology and the doctrines of Christianity, e.g., masturbation and (d) the problem of evil. (He put up a slide with a picture of the tablet that would normally have the 10 commandments on it, but instead had "Thou shalt not masturbate". This was pretty funny, especially because when it was Pastor Wilkinson's turn to speak, the slide stayed up behind him.)

Pastor Wilkinson spoke again. In the materialist world view, he claimed, there was no objective standard of morality, or right and wrong. No god implies no morality. Hitler based his world view on Darwin's view of natural selection. If the materialist world view is correct, there is nothing wrong with Hitler's murders. Evolutionary biologists agree that the theory of evolution arose because people want to get away from traditional sexual morality (he quoted Huxley).

Next, there was some final cross-examination. Prof. diCarlo got Wilkinson to admit that God hates all believers in other religions except Wilkinson's brand of Christianity. In particular, Wilkinson explicitly stated that God hates Muslims! Now that was a rather explosive claim, but entirely missing from the Record's account of the debate by religion reporter Mirko Petricevic. I have observed that Petricevic constantly slants his coverage to favor the religious point of view, and this is just another data point.

Prof. diCarlo also made some effective points about the incompatibility of the Christian god with human free will. The Christian god's view of us is the same way: since his is omniscient and created the universe, he already knew 14 billion years ago whether we would be saved or not. We can do nothing to defeat his knowledge and so don't have free will. He made an analogy with the movie "Jaws": you can watch it as many times as you like, but the shark always dies at the end. God watching history unfold is the same. Pastor Wilkinson had no good response to this argument.

In his closing remarks, Pastor Wilkinson made the point that only Christianity, among all religions, must be true because in no other religion is there justice. In particular, Islam does not provide justice for evil deeds during life. But I felt he contradicted himself, since he made two claims: Christianity provides justice, but one can also be saved if one repents on one's deathbed. In other words, Hitler could be in heaven if he repented and asked god's forgiveness at the last moment. So how is that justice?

At this point the debate ended, and I will now give some comments without resorting to red and italics.

First, both speakers had polished presentations. Pastor Wilkinson's closing remarks, in particular, were an earnest sermon about man's need for Christianity, and they were well-received by many of the believers in the crowd. Prof. diCarlo's brand of sardonic humor succeeded in making many points, particularly about Wilkinson's condemning Jews, homosexuals, and Muslims to hell.

On the other hand, both speakers could have addressed the other's arguments in more detail. It was almost as if we had two parallel presentations which, despite the opportunity for cross-examination, didn't interact all that much. Prof. diCarlo, for example, never really addressed Pastor Wilkinson's point about the "laws of logic", which was really his main argument. Also, while I admired his wit and intellect, I felt Prof. diCarlo sometimes came across as a little too flippant and arrogant. It sometimes seemed like he treated the audience as a philosophy class where he was the instructor.

After the debate, I asked Pastor Wilkinson the following question: "You say the earth is 10,000 years old. Yet there are ice cores in Antarctica that give an unbroken record of 190,000 years. How do you explain this?" He had no good answer, mumbling about "uniformity" and "assumptions". But the ice core record we have agrees with data in the recent past, and there is no reason to believe it does not actually represent a record of history. When pressed, he suggested a comet might have exploded in the atmosphere and just happened to put down a series of layers that exactly correspond to our historical record. But, of course, this is just pure fantasy. Where is the evidence for this comet? How did it happen to put down a series of layers that exactly matches our historical records? I made the point to him that no thinking person is going to subscribe to Wilkinson's version of Christianity if it causes him to deny the evidence of his own senses.

For me it was an entertaining evening, but probably not one that changed many minds.

Sunday, February 05, 2006

Tucson - Day 5

Last night, some visitors from home arrived, and today we'll all go together to see more of the gem and mineral show.

One of the visitors is Peter Russell, curator of the Earth Sciences Museum at the University of Waterloo -- a place well worth a visitor if you are ever in southern Ontario. He's looking for new specimens for the Museum, so the first place we'll go is the InnSuites Hotel on Granada, which is sort of a mecca for fossil dealers.

In the fossil ballroom there, you can find all sorts of fossils and fossil-related items. Beware: some of the prices are rather high! One ballroom dealer was selling opalized Cleoniceras ammonites from Madagascar for $150, but you can get a whole flat of similar ones for the same price a few blocks away, at the Ramada Inn.

One thing I really liked was a giant fossil palm tree from Wyoming, but unfortunately the owners would not allow me to put a picture on my blog. You'll have to make do with this spectacular opalized ammonite from Alberta. The picture doesn't show the scale, but this thing is about the size of a laundry basket:

Gem quality opalized ammonite is known as "ammolite" in the trade, and there is a semi-secret procedure for stabilizing it and making it suitable for jewelry.

Of course, the InnSuites is not just fossils. Konstantin Buslovich of Phantom was selling this beautiful heliodor (a variety of beryl, the same family as aquamarine and emerald) from Ukraine, a steal at only $9300. Unfortunately I forgot to bring my $10,000 bill.

Outside the InnSuites, in a huge tent to the west, we found the Granada Avenue Mineral Show. A giant triceratops skull guards the entrance to the street. Here it is ferociously munching down on an unsuspecting van:

This show consisted of only five dealers, but one of them, Aurora Mineral Corp., had this really spectacular quartz geode, larger than a refrigerator:

This will be my last post from Tucson. Tomorrow I have to pack and get ready to head back home. Hope you enjoyed the trip as much as I did!

One of the visitors is Peter Russell, curator of the Earth Sciences Museum at the University of Waterloo -- a place well worth a visitor if you are ever in southern Ontario. He's looking for new specimens for the Museum, so the first place we'll go is the InnSuites Hotel on Granada, which is sort of a mecca for fossil dealers.

In the fossil ballroom there, you can find all sorts of fossils and fossil-related items. Beware: some of the prices are rather high! One ballroom dealer was selling opalized Cleoniceras ammonites from Madagascar for $150, but you can get a whole flat of similar ones for the same price a few blocks away, at the Ramada Inn.

One thing I really liked was a giant fossil palm tree from Wyoming, but unfortunately the owners would not allow me to put a picture on my blog. You'll have to make do with this spectacular opalized ammonite from Alberta. The picture doesn't show the scale, but this thing is about the size of a laundry basket:

Gem quality opalized ammonite is known as "ammolite" in the trade, and there is a semi-secret procedure for stabilizing it and making it suitable for jewelry.

Of course, the InnSuites is not just fossils. Konstantin Buslovich of Phantom was selling this beautiful heliodor (a variety of beryl, the same family as aquamarine and emerald) from Ukraine, a steal at only $9300. Unfortunately I forgot to bring my $10,000 bill.

Outside the InnSuites, in a huge tent to the west, we found the Granada Avenue Mineral Show. A giant triceratops skull guards the entrance to the street. Here it is ferociously munching down on an unsuspecting van:

This show consisted of only five dealers, but one of them, Aurora Mineral Corp., had this really spectacular quartz geode, larger than a refrigerator:

This will be my last post from Tucson. Tomorrow I have to pack and get ready to head back home. Hope you enjoyed the trip as much as I did!

Saturday, February 04, 2006

Tucson - Day 4

For those who haven't been to the Tucson gem and mineral show, here's a brief description.

As I mentioned before, it's not just one show, it's actually dozens. There are shows devoted to fossils and minerals, shows for gemstones, jewelry shows, bead shows, and shows for native American artifacts. Some are retail, some are wholesale only, and some are a mixture of both. Although I've attended the show 3 times since 2002, I've still only visited a small portion of what there is to see.

Some shows take place in hotel rooms. The dealers sleep and display in the same room. When they wake up in the morning, the beds are made, personal items are put away, and the minerals come out. Many people display their minerals on the hotel room beds and tables, and some have displays on tables outside the room.

Other shows take place in the Tucson Convention Center, or in the large tent across the street.

Shows definitely have their own character. For example, among mineral shows, the one at the Westward Look is for very high end collectors, those that don't bat an eye at paying four or five figures or more for a single specimen. Below that in average specimen cost are the shows organized by Marty Zinn, at venues like the Inn Suites Hotel and Clarion. And even below that are the shows along the freeway, such as at the Howard Johnson's, and the show at Tucson Electric Park. Many dealers head for the cheaper shows to pick up items that they then resell for twice the price (or more) at their own shows.

Here's an example. Among meteorite aficionados, the iron meteorites from Campo del Cielo in Argentina are held in low regard, in part because they are so common. They are probably the cheapest meteorites in price per gram. A dealer named "Giroldi" was selling them at the Howard Johnson's, with literally hundreds of specimens available. Here he is, posed with one of the largest pieces:

Later, I saw exactly the same meteorites for sale by meteorite dealers at the Inn Suites for twice the price. The lesson is that if you head down here, you might want to check out the cheaper shows first to see what the prices are.

I didn't spend much time at the show today. Instead, I went hiking with an old friend and colleague from Tucson.

It's been extremely dry here in the Southwest; the last significant precipitation in Tucson was almost a year ago. Normally Mt. Lemmon, to the north of Tucson, has a ski season, but not this year, since there is no snow.

We headed for the San Pedro River, the valley that is to the southeast of Tucson. This is an area that is famed for birding because it is one of the few places where there is running water. We got a late start, so we didn't see too many interesting birds. But I did notice how dry it was. Normally the cottonwoods would be much greener this time of year.

As I mentioned before, it's not just one show, it's actually dozens. There are shows devoted to fossils and minerals, shows for gemstones, jewelry shows, bead shows, and shows for native American artifacts. Some are retail, some are wholesale only, and some are a mixture of both. Although I've attended the show 3 times since 2002, I've still only visited a small portion of what there is to see.

Some shows take place in hotel rooms. The dealers sleep and display in the same room. When they wake up in the morning, the beds are made, personal items are put away, and the minerals come out. Many people display their minerals on the hotel room beds and tables, and some have displays on tables outside the room.

Other shows take place in the Tucson Convention Center, or in the large tent across the street.

Shows definitely have their own character. For example, among mineral shows, the one at the Westward Look is for very high end collectors, those that don't bat an eye at paying four or five figures or more for a single specimen. Below that in average specimen cost are the shows organized by Marty Zinn, at venues like the Inn Suites Hotel and Clarion. And even below that are the shows along the freeway, such as at the Howard Johnson's, and the show at Tucson Electric Park. Many dealers head for the cheaper shows to pick up items that they then resell for twice the price (or more) at their own shows.

Here's an example. Among meteorite aficionados, the iron meteorites from Campo del Cielo in Argentina are held in low regard, in part because they are so common. They are probably the cheapest meteorites in price per gram. A dealer named "Giroldi" was selling them at the Howard Johnson's, with literally hundreds of specimens available. Here he is, posed with one of the largest pieces:

Later, I saw exactly the same meteorites for sale by meteorite dealers at the Inn Suites for twice the price. The lesson is that if you head down here, you might want to check out the cheaper shows first to see what the prices are.

I didn't spend much time at the show today. Instead, I went hiking with an old friend and colleague from Tucson.

It's been extremely dry here in the Southwest; the last significant precipitation in Tucson was almost a year ago. Normally Mt. Lemmon, to the north of Tucson, has a ski season, but not this year, since there is no snow.

We headed for the San Pedro River, the valley that is to the southeast of Tucson. This is an area that is famed for birding because it is one of the few places where there is running water. We got a late start, so we didn't see too many interesting birds. But I did notice how dry it was. Normally the cottonwoods would be much greener this time of year.

Friday, February 03, 2006

Tucson - Day 3 - Interview with Steve Smale

Stephen Smale is a world-famous mathematican and winner of the 1966 Fields Medal, mathematics' highest award. He's also a famous mineral collector, with one of the world's best private collections, and he has a new book coming out in April, featuring his collection. I had the chance to sit down with him this morning at his room at the Westward Look Resort and talk about politics, mathematics, and minerals. A Recursivity exclusive!

I've transcribed our discussion from a cassette tape. I've rearranged the discussion a bit, omitted some parts that were inaudible on the tape, and removed some others, but other than that, this transcription is more or less verbatim.

JOS: You were actively involved in protests against the Vietnam War at Berkeley. I'd like to know if you see any parallels between that time and now.

SS: Yeah, sure. Iraq has quite a bit of parallels with Vietnam.

JOS: Have you been moved to react in any manner?

SS: No, I'm not an activist these years. I was in a demo in Chicago, an anti-war vigil in Chicago, and I still have some activist friends. You know, a little bit. I'm not an activist, although my sympathies are with Cindy Sheehan.

JOS: I know that at one point you were working on your autobiography, and you completed a chapter or so. But then I came across the biography by Batterson. Do you still plan to work on an autobiography?

SS: No. With that book out, I don't think so. I published something called "Some autobiographical notes" - I think it's in my collected works. If it's not there, it's certainly in the volume for my 60th birthday. I think Batterson used those notes since they were already published when he wrote the book.

But after that book he's written... He really did a good job on it. He's very thorough, scholarly and accurate.

JOS: So, are you happy with the Batterson biography?

SS: Yes, I am. Especially from the point of view of being very accurate, careful, and documented. He doesn't in fact, indicate how careful he is. I mean, so many of his quotes are taken from taped interviews. He doesn't say that anywhere! He should, because people would then realize the authenticity of it. But, you know, the quotes are taken in general from taped interviews, and he has the tapes, so he has very thorough documentation. So from that point of view I think it's great.

In general. There's a couple of things that maybe... you know, he approached me like a mathematician in some sense. In some sense, I see myself a little more broadly as a scientist, not just a mathematician.

JOS: In the past, you've spoken enthusiastically about computer science and the challenges it brings to mathematics. Are you still enthusiastic along those lines?

SS: Yes, my main job is in a computer science institute.

JOS: Yes, at Toyota Technological Institute.

SS: Yes, that's the place, it was founded by computer scientists, it's a computer science institute.

But I do have a little different point of view from the computer science community. And I even have some conflicts with the computer science department at the University of Chicago and Toyota.

To oversimplify it, I come from the more continuous version of science and mathematics. Computer scientists tend to come from the discrete tradition. And you know, that brings us to some different points of view. My own conflict there is that the computer science department in which I am in is very narrowly focussed, in seeing so much of the science in terms of the discrete computer science tradition. So there have been some conflicts over hiring people.

I like to hire people that have a more deep mathematical perspective, not necessarily mathematicians, in fact not mathematicians, usually physicists who have a very good, sound training in mathematics. I wanted to hire this person to be an assistant professor, and I was voted down. So there are these kinds of conflicts. You know, I see myself criticizing the mathematics community and similarly the computer science community, and I think any similar community, as too much narrowly focussed around a tradition, and not understanding things happening outside of it.

JOS: I see that some of your latest work is on evolution of language, and also one of your open problems for the new century is on the limits of intelligence.

SS: That's the problem that I work on all the time now, for five years. We call it learning theory. It talks about the fundamental problems of intelligence and learning, both from the human and machine side. A lot has been happening in this area, called learning theory.

JOS: The limits of intelligence is a very deep problem. It's not going to have a quick solution.

SS: Right. (laughs) Right. But you know, learning theory is the closest part of a solid science dealing with both.

JOS: Since the word intelligence has come up, I can't resist asking your opinion of the intelligent design movement, if you've followed it at all.

SS: I don't follow it. You know, I'm pretty negative about it, about the religious basis of science. I don't pay much attention to it.

JOS: Let me ask you about electronic journals. That's a development that's happened in the last 10 years that's really grown. Do you think it's a positive development?

SS: Yeah. But I don't think of it too much in those terms. I just think in general the computer, the transmission of information via Internet, is a revolution, a change in the way one thinks about libraries and information and research. It affects me a huge amount. I don't hardly ever use libraries nowadays. I used to use libraries, 30 years ago, intensively. I used to just, you know, browse in libraries a huge amount. Now I browse on the Internet.

So I wouldn't want online journals to be the main focus. You need to think in the more broad sense. I use Google, not online journals. When I want to find something I want to learn about, I use Google. Sometimes Google, sometimes Google Scholar, sometimes other things, but I start with Google, type in a few keywords. So that's quite a revolutionary way of researching, doing research in science

JOS: Do you think that in the future it will be mostly preprint archives, with no refereeing process, and people decide the quality on their own, or is there still a place for peer review?

SS: (Laughs) Well, there's probably some place for peer review, yeah, I think there is. Getting some feedback is important. When I was young, peer-reviewed papers were the main method, and now. But it's been gradually happening, even before internet, preprints were more and more common, and finally internet. But you know, when I was a student, preprints were very rare.

JOS: Maybe we could turn to minerals now. Do you think being a mathematician influenced you strongly in becoming a mineral collector, or is it more or less coincidental?

SS: Oh, I don't know. I wouldn't say either. Maybe coincidental is closer. I don't believe much in coincidences, you know, there is a background. It started with Clara, and with my father, who bought me a mineral.

I don't see collecting as too close to mathematics. There is a kind of beauty I find in minerals, like I say in my new book, the beauty of natural crystals. So I support the beauty more than the scientific side. In my book I say, this is not a scientific book. It's not an art book either. But it's closer to an art book than a scientific book. And I don't follow the mathematics of crystallography.

JOS: Did you ever collect in the field?

SS: No, I never collect in the field. I've been in some mines. I don't purchase things so much, I trade.

JOS: On your website you say that in 1969 it was possible for a person of

moderate means to assemble a mineral collection that would rival those of museums. Do you think that's still true?

SS: Probably. Mineral museums don't really have the resources. Individuals have more money to spend each year for minerals than museums. Museums sometimes have endowed mineral collections, but if they're not careful, they get sold away. So, you know, you can compete with museums for minerals. Museums are occasionally endowed, like the one in Houston.

JOS: What do you think of that book, Masterpieces of the Mineral World?

SS: It's good, it's a good book. It's a very good book. Yeah. But you know, I have some issues with the book. First of all, it doesn't give enough credit to the main contributor, Jeff Scovil, in the book itself. So there was a big outcry about that and eventually they added something. The book itself just has a small mention, a note.

You know, our book is going to be a lot better as far as the processing of photographs. We do it in Germany, not in Asia. And we pay a lot more attention to processing the photo. I mean it's the difference between the Mineralogical Record. We have a picture there, you probably saw it, every month, every issue, which I think is not too good. Yeah, it's better than most magazines, but it's not nearly as good as extraLapis. You know extraLapis?

JOS: Yes.

SS: There they have a very, very good photograph reproduction, it's accurate. So our book is being published by extraLapis. Their first book, actually.

JOS: Congratulations.

SS: So we put a lot of effort into it. We've gone through each photograph from the printer this week, looking very carefully at the color tones and accuracy with the editors of extraLapis. It's something that has not been done with photographs in the Mineralogical Record. They're sloppy at the Mineralogical Record. I mean, they're better than most magazines.

Back to the Houston book, that did suffer because they didn't have the contrasting tones and accuracy, so the minerals don't stand out on the page. It's not bad, it's one of the best books. The best book is Bancroft, Gem and, uh.

JOS: Gem and Crystal Treasures.

SS: Yeah, I think that's the best book.

JOS: I notice that at shows, older people predominate. Do you think the hobby is dying?

SS: No, no, I don't think so. The big show here is dominated by younger people, in my opinion. At the shows, all the big names are young. Big dealers, big collectors. Stuart Wilensky, Rob Lavinsky. All the big dealers are young. They're driving the whole Internet market. I don't see too much of the people out on the floors at shows. I don't know if their age has changed. Certainly there are some aspects that younger people may not be interested in as much as they were 30 years ago. Rocks shops have been replaced by shows and the Internet. But I see many of the dealers, they're young, very forceful people. They're all in their 30's. Rob Lavinsky, he's probably 30 by now.

JOS: I know that for a while the Blue Cap tourmaline you were famous for was one of your favorites. What's one of your current favorites?

SS: It's not a question of a single piece. Phosphophyllite. Jeremejevite. Aquas and tourmalines are some of the best.

JOS: There's a nice phosphophyllite in the Masterpieces book.

SS: Yeah, it's good. I like ours quite a bit better, though. Theirs is restored. That's one reservation I have about their book, they put in repaired and restored pieces without saying they were repaired or restored.

When people are selling, they're better about it. But in the Masterpieces book, they should have said repaired or restored.

JOS: Thank you very much.

SS: Thank you.

Thursday, February 02, 2006

Tucson - Day 2

Still here in Tucson at the mineral and gem show.

I started this morning at the Smuggler's Inn, far on the east side of town. This show is dominated by the large number of foreign dealers, particularly from China and Russia. If you're looking for fluorite, wolframite, cinnabar, scheelite, or blue apatite, this is the place for you.

For me, some of the nicest specimens here were the large green fluorites from Hunan province. Here a gentleman from the Huanqiu Crystal Mineral Museum is holding one:

One of the nice things about the show is meeting people you've read about before in places like the Mineralogical Record. Here's the legendary Alfredo Petrov, a specialist in Bolivian minerals:

After a few hours at the Smuggler's, I went on to the Inn Suites. First, it was off to say hello to Richard Sittinger, who runs the Mineral of the Month Club. He seemed pretty busy!

Next, I stopped in to see Bill and Anne Cook of Virgin Valley Sales, who always have a large number of rare and unusual minerals for sale.

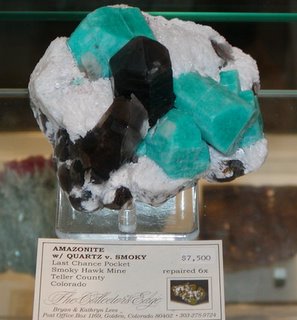

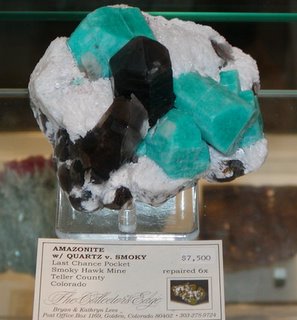

Now for the minerals. Here's a spectacular amazonite and smoky quartz from The Collector's Edge.

And here's a beautiful smithsonite from the same dealer:

Dilermando Rodrigues de Melo kindly posed with this amazing pink glassy kunzite from Minas Gerais:

And Vasconcelos Brazil had this spectacular large quartz cluster for sale. Note my cell phone at the lower left for scale.

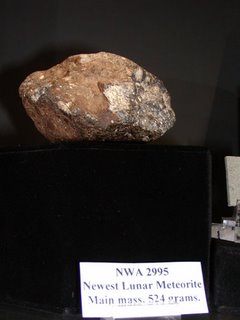

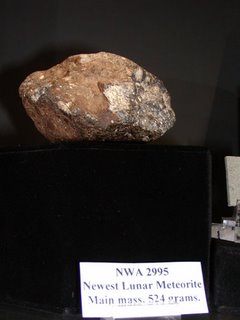

Many meteorite dealers have rooms at the Inn Suites. Mike Farmer is one of the most famous meteorite hunters; he had a new lunar meteorite, which he kindly posed with:

Lunar meteorites are chunks of the moon that have been knocked off by an impact. They float around in space for a while and sometimes eventually hit the earth, but it takes a trained eye and laboratory analysis to recognize them (we know from the Apollo missions what moon rocks look like). And here's the meteorite by itself:

There was also a reception in honor of Steve Arnold, a meteorite hunter who found the new main mass of the Brenham, Kansas pallasite this fall. Here he is with this 640 kg specimen:

Pallasites are stony-iron meteorites that consist of olivine crystals floating in a matrix of iron-nickel. They are believed to be parts of asteroids where the mantle and core meet.

Signing off for now - more tomorrow.

I started this morning at the Smuggler's Inn, far on the east side of town. This show is dominated by the large number of foreign dealers, particularly from China and Russia. If you're looking for fluorite, wolframite, cinnabar, scheelite, or blue apatite, this is the place for you.

For me, some of the nicest specimens here were the large green fluorites from Hunan province. Here a gentleman from the Huanqiu Crystal Mineral Museum is holding one:

One of the nice things about the show is meeting people you've read about before in places like the Mineralogical Record. Here's the legendary Alfredo Petrov, a specialist in Bolivian minerals:

After a few hours at the Smuggler's, I went on to the Inn Suites. First, it was off to say hello to Richard Sittinger, who runs the Mineral of the Month Club. He seemed pretty busy!

Next, I stopped in to see Bill and Anne Cook of Virgin Valley Sales, who always have a large number of rare and unusual minerals for sale.

Now for the minerals. Here's a spectacular amazonite and smoky quartz from The Collector's Edge.

And here's a beautiful smithsonite from the same dealer:

Dilermando Rodrigues de Melo kindly posed with this amazing pink glassy kunzite from Minas Gerais:

And Vasconcelos Brazil had this spectacular large quartz cluster for sale. Note my cell phone at the lower left for scale.

Many meteorite dealers have rooms at the Inn Suites. Mike Farmer is one of the most famous meteorite hunters; he had a new lunar meteorite, which he kindly posed with:

Lunar meteorites are chunks of the moon that have been knocked off by an impact. They float around in space for a while and sometimes eventually hit the earth, but it takes a trained eye and laboratory analysis to recognize them (we know from the Apollo missions what moon rocks look like). And here's the meteorite by itself:

There was also a reception in honor of Steve Arnold, a meteorite hunter who found the new main mass of the Brenham, Kansas pallasite this fall. Here he is with this 640 kg specimen:

Pallasites are stony-iron meteorites that consist of olivine crystals floating in a matrix of iron-nickel. They are believed to be parts of asteroids where the mantle and core meet.

Signing off for now - more tomorrow.

Wednesday, February 01, 2006

Tucson - Day 1

I'm down in Tucson, Arizona, visiting the annual Tucson Gem and Mineral Show. Actually, it's several dozen different shows, each with many, many dealers selling rocks, minerals, gems, fossils, meteorites, jewellery, and more.

I'm really tired, because while I made a short connection at O'Hare yesterday, one of my bags didn't, so I ended up spending another two hours in the Phoenix airport waiting for it to catch up with me.

Today, I spent the whole day at one of the Arizona Mineral and Fossil Shows, at the Clarion Hotel on Alvernon. Lots of very beautiful minerals, most out of my price range! In fact, I'd like to title this day "in quest of the 6-figure specimen".

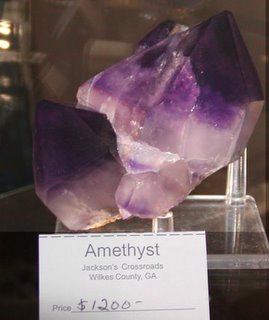

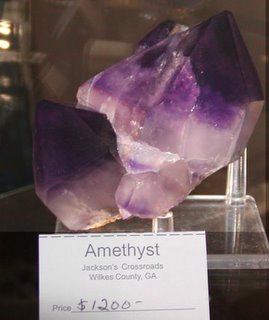

To start off with, this past summer there was a nice find of amethyst at Jackson's Crossroads in Wilkes County, Georgia, and they were available at Mountain Gems and Minerals. The color is really good, but as you can see, I'm still only at 4 figures.

Gold, of course, is always good for a nice price, and this native gold from Mineral Exploration Services at Lehigh Minerals is no exception. But we're still only at 4 figures.

Next, I was off to see Jordi Fabre at Fabre Minerals, one of Spain's premier dealers.

He had some really beautiful items, including this aquamarine in the high 4 figures.

Another nice piece was this rhodochrosite from the classic ___location of the Sweet Home Mine, from Isaias Casanova at IC Minerals. Amazing color!

To get to 5 figures, I went to Matrix India, where M. F. Makki had this really gigantic green apophyllite on stilbite from Momin Akhada, near Rahuri, Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra State, India. These deposits are often found when wells are being dug.

It's hard to tell from the photo, but this specimen is the size of a small refrigerator!

But to get to 6 figures, I had to go to Ausrox, where an amazing Pakistani aquamarine was on sale for $100,000. A little out of my price range!

Whew, all those expensive minerals have me exhausted. Now it's time to go see some rare ones.

The goal of the species collector is to have an example of every known mineral. Since there are more than 4,000 minerals currently known, with dozens of new ones found each year, this can be a real challenge. Luckily, at Tucson there are people to help.

Tony Nikischer runs Excalibur Mineral Corporation. He brought over 3100 different species to Tucson, and was kind enough to let me look through his flats of rare minerals. He also does mineral analysis, and edits Mineral News. There's even a mineral named after him! Here's his smiling face:

And another nice gentleman is Dr. Jaroslav Hyršl, co-author of the wonderful reference book Minerals and Their Localities. He's also got lots of rare species, mostly from Europe, and is very knowledgeable and friendly.

Well, that's all for today. Stay tuned, I may have some surprises later.

I'm really tired, because while I made a short connection at O'Hare yesterday, one of my bags didn't, so I ended up spending another two hours in the Phoenix airport waiting for it to catch up with me.

Today, I spent the whole day at one of the Arizona Mineral and Fossil Shows, at the Clarion Hotel on Alvernon. Lots of very beautiful minerals, most out of my price range! In fact, I'd like to title this day "in quest of the 6-figure specimen".

To start off with, this past summer there was a nice find of amethyst at Jackson's Crossroads in Wilkes County, Georgia, and they were available at Mountain Gems and Minerals. The color is really good, but as you can see, I'm still only at 4 figures.

Gold, of course, is always good for a nice price, and this native gold from Mineral Exploration Services at Lehigh Minerals is no exception. But we're still only at 4 figures.

Next, I was off to see Jordi Fabre at Fabre Minerals, one of Spain's premier dealers.

He had some really beautiful items, including this aquamarine in the high 4 figures.

Another nice piece was this rhodochrosite from the classic ___location of the Sweet Home Mine, from Isaias Casanova at IC Minerals. Amazing color!

To get to 5 figures, I went to Matrix India, where M. F. Makki had this really gigantic green apophyllite on stilbite from Momin Akhada, near Rahuri, Ahmednagar District, Maharashtra State, India. These deposits are often found when wells are being dug.

It's hard to tell from the photo, but this specimen is the size of a small refrigerator!

But to get to 6 figures, I had to go to Ausrox, where an amazing Pakistani aquamarine was on sale for $100,000. A little out of my price range!

Whew, all those expensive minerals have me exhausted. Now it's time to go see some rare ones.

The goal of the species collector is to have an example of every known mineral. Since there are more than 4,000 minerals currently known, with dozens of new ones found each year, this can be a real challenge. Luckily, at Tucson there are people to help.

Tony Nikischer runs Excalibur Mineral Corporation. He brought over 3100 different species to Tucson, and was kind enough to let me look through his flats of rare minerals. He also does mineral analysis, and edits Mineral News. There's even a mineral named after him! Here's his smiling face:

And another nice gentleman is Dr. Jaroslav Hyršl, co-author of the wonderful reference book Minerals and Their Localities. He's also got lots of rare species, mostly from Europe, and is very knowledgeable and friendly.

Well, that's all for today. Stay tuned, I may have some surprises later.

Sunday, January 29, 2006

Provo Daily Herald Kicks Buttars

Utah state senator D. Chris Buttars is at it again.

Buttars is the blockhead who planned to introduce a bill mandating the teaching of "divine design" in Utah schools, but withdrew under criticism. Now he's introduced Utah Senate Bill 96, which demands, among other things that "instruction to students on any theory regarding the origins of life, or the origins or present state of the human race, shall stress that not all scientists agree on which theory is correct."

But why stop there? After all, some scientists don't agree with relativity theory, either. Why should Einstein get a monopoly in Utah schools?

Thankfully, some people in Utah are standing up to this kakocrat. An editorial in the Provo Daily Herald is right on the point: "House should reject creationism bill". And the Salt Lake Tribune says the bill "[belittles] evolutionary principles in favor of an unwritten but clearly religious view of a very narrow kind".

Utahns, call your state senator today and state your opposition to this stupid and dishonest bill.

Buttars is the blockhead who planned to introduce a bill mandating the teaching of "divine design" in Utah schools, but withdrew under criticism. Now he's introduced Utah Senate Bill 96, which demands, among other things that "instruction to students on any theory regarding the origins of life, or the origins or present state of the human race, shall stress that not all scientists agree on which theory is correct."

But why stop there? After all, some scientists don't agree with relativity theory, either. Why should Einstein get a monopoly in Utah schools?

Thankfully, some people in Utah are standing up to this kakocrat. An editorial in the Provo Daily Herald is right on the point: "House should reject creationism bill". And the Salt Lake Tribune says the bill "[belittles] evolutionary principles in favor of an unwritten but clearly religious view of a very narrow kind".

Utahns, call your state senator today and state your opposition to this stupid and dishonest bill.

Saturday, January 28, 2006

Time Travel

I am travelling in time this weekend.

The Time Tunnel has just been released on DVD, and for a few hours it is 1966 and I am nine years old again, anxiously looking forward to another Friday night on ABC with our little black-and-white television set. Where will Doug and Tony end up this time? Will they ever get home?

Vietnam was just something grown-ups were arguing about. The wonders and terrors of sex were a long way in the future. Our astronauts were practicing for the moon, and I couldn't wait for them to get there. Munich was six years away and unimaginable.

I was still reading The Happy Hollisters, but the magic was beginning to wear off. I didn't want to be Ricky any more, but Pete seemed much too old. And besides, something new beckoned: I had discovered chemistry.

Every day after school I'd head down to the basement, to make blue ink, or an exploding volcano, or turn water into wine. I ran electricity through water and made test tubes full of hydrogen and oxygen, then mixed them together and exploded them with a match. I put too much silver nitrate down the sink and ruined the porcelain. Once day I got a brilliant idea to make a hydrogen blowtorch, and probably would have lost an eye if I hadn't been wearing glasses. My parents never heard about that episode.

I raced through Glenn Seaborg's inspiring account of how he discovered elements beyond uranium. Science was the answer to the world's problems, I was sure. Science would take us to the stars, provide free power, and cure our diseases.

In real life, I am nursing a cold, watching the episodes on DVD with my children, one of whom is the same age I was in 1966. The cheesiness of the plots and the crappy movie sets don't bother us. My kids feel the same wonder at the possibility of zipping through the ages as I did.

I know it's 2006 in real life, but in my head it's forty years ago. My father is still alive, with a mind undamaged by Alzheimer's, and ready to answer my questions. Is time travel really possible, Dad? Will there be bases on the moon when I grow up? Will I go there? Will you come with me, Dad?

Who says you can't travel in time?

The Time Tunnel has just been released on DVD, and for a few hours it is 1966 and I am nine years old again, anxiously looking forward to another Friday night on ABC with our little black-and-white television set. Where will Doug and Tony end up this time? Will they ever get home?

Vietnam was just something grown-ups were arguing about. The wonders and terrors of sex were a long way in the future. Our astronauts were practicing for the moon, and I couldn't wait for them to get there. Munich was six years away and unimaginable.

I was still reading The Happy Hollisters, but the magic was beginning to wear off. I didn't want to be Ricky any more, but Pete seemed much too old. And besides, something new beckoned: I had discovered chemistry.

Every day after school I'd head down to the basement, to make blue ink, or an exploding volcano, or turn water into wine. I ran electricity through water and made test tubes full of hydrogen and oxygen, then mixed them together and exploded them with a match. I put too much silver nitrate down the sink and ruined the porcelain. Once day I got a brilliant idea to make a hydrogen blowtorch, and probably would have lost an eye if I hadn't been wearing glasses. My parents never heard about that episode.

I raced through Glenn Seaborg's inspiring account of how he discovered elements beyond uranium. Science was the answer to the world's problems, I was sure. Science would take us to the stars, provide free power, and cure our diseases.

In real life, I am nursing a cold, watching the episodes on DVD with my children, one of whom is the same age I was in 1966. The cheesiness of the plots and the crappy movie sets don't bother us. My kids feel the same wonder at the possibility of zipping through the ages as I did.

I know it's 2006 in real life, but in my head it's forty years ago. My father is still alive, with a mind undamaged by Alzheimer's, and ready to answer my questions. Is time travel really possible, Dad? Will there be bases on the moon when I grow up? Will I go there? Will you come with me, Dad?

Who says you can't travel in time?

Thursday, January 26, 2006

Local Bigot Headed for Ottawa

Voters in my neighboring riding of Kitchener-Conestoga have elected a local bigot, Harold Albrecht, as their representative in the Parliament of Canada. Shame on them.

For those who read our local paper, the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, Albrecht is infamous for a series of misinformed and nasty rants against sex and gay marriage. Here is a selection:

In an opinion piece published in the Record on October 29, 1993, Albrecht falsely claimed that "An analysis by researchers at the University of Texas estimates that when condoms are used, the risk of acquiring HIV from an infected partner is 31 per cent over a year's time. This study was reported in the Journal of Social Science and Medicine in June 1993."

Albrecht was evidently referring to this paper: Susan C. Weller, A meta-analysis of condom effectiveness in reducing sexually transmitted HIV, Social Science and Medicine 36 (12) (1993), 1635-1644. It's clear Albrecht never read the article, because he gets the title of the journal wrong: it's not the Journal of Social Science and Medicine, but simply Social Science and Medicine.

More importantly, Albrecht seriously misrepresented the conclusions of the Weller study. In the abstract, Weller concludes that "condoms may reduce risk of HIV infection by approximately 69%." A casual reader might think Albrecht is right, since 100% - 69% = 31%.

He's not. Albrecht is mixing up apples and oranges. The 69% figure of Weller represents the reduction in risk associated with using a condom. Let's say that the risk of getting HIV from an infected partner over one year's time without a condom is 10% (Weller's 1993 meta-analysis found figures varying from 4% to 19%). Then a 69% risk reduction means that with a condom, the risk of contracting HIV from an infected partner in one year decreases to about 3%. And 3% ain't 31%. Albrecht is either misinforming us, repeating misinformation, or innumerate -- not the best resumé for somebody headed to Ottawa to run things.

Furthermore, one should note that in 1999 Weller disavowed her 1993 study (see here), admitting that her earlier result was "was flawed because it aggregated studies with varying definitions of condom use, directions of transmission, study designs and types of index cases." In the newer paper [Karen R. Davis and Susan C. Weller, The Effectiveness of Condoms in Reducing Heterosexual Transmission of HIV, Family Planning Perspectives 31 (6) November/December 1999] Weller concluded that if one always uses a condom, the rate of transmission is 0.9 per 100 person years, or about 1% -- a far cry from Albrecht's 31%. (I'm not claiming Albrecht should have known in 1993 about a 1999 study, just showing his figures are all wrong.)

Albrecht next went on to claim "At a 1991 national conference on HIV held in Washington, D.C., none of the 800 sexologists raised a hand when asked if they would trust a thin rubber sheath to protect them during intercourse with a known HIV-infected person." This claim appears to be plagiarized practically verbatim from a 1992 fund-raising letter from known liar James Dobson. I doubt this incident ever happened. But even if it did, so what? All other things being equal, I wouldn't hold a gun to my head and pull the trigger, if it contained 100 empty chambers and 1 bullet. But, of course, all other things aren't equal. The Weller figures are for sex with a known HIV-positive partner, whereas what Albrecht is really getting upset about is teens having sex with other teens. Guess what? The HIV-infection rate among teens in Canada is quite small, so their risk of contracting HIV using a condom is much, much less than 1% in a year.

Albrecht then said, "Small wonder, when you consider that the human immunodeficiency virus is 1-25th the width of sperm and can pass easily through the smallest gaps in condoms." This claim is truly moronic. After all, water molecules are even smaller than viruses, but they don't seem to pass so easily through a condom. The World Health Organization debunks Albrecht's claim, stating that "Laboratory studies have found that viruses (including HIV) do not pass through intact latex condoms even when devices are stretched or stressed." Who are you going to believe, a prestigious non-partisan health group, or a bigoted fundamentalist?

Finally, Albrecht concludes with this admonishment: "Some of our brightest and best young people are being placed in a position of grave danger by being fed half-truths which, by simple mathematical deduction, are also half-lies." Pretty ironic, considering all the misinformation Albrecht was dishing out.

In 1995, Albrecht wrote a nasty opinion piece against Planned Parenthood, snidely suggesting it should change its name, and false claiming "The work of Planned Parenthood has very little to do with planning." Actually, most of their work, from workshops to condom distribution, concerns planning.

In 2002, Albrecht wrote an opinion piece in which he claimed "Child pornography is considered to be an art form". Nothing supporting this bizarre claim was advanced. He also took objection to a local performance of Puppetry of the Penis, saying "I appeal to Kitchener council to "close the lid" and cancel this event." I'm sure that when Albrecht gets to Ottawa, we can expect similarly stirring defenses of freedom of expression.

In 2003, Albrecht produced one of his most despicable rants, this time against gay marriage. He said "If one is truly committed to the marriage vows of fidelity, these same-sex marriages would succeed in wiping out an entire society in just one generation. So much for a bigger family." What ignorance! I have two relatives in a same-sex marriage, and they are happily raising two children with no infidelity involved. (I leave it for those with an outlook slighly broader than Albrecht's to figure out how.)

He went on to say "Nature alone points to the ridiculous "wisdom" of calling these relationships marriage. Thankfully, only a very small percentage of people will fall for this thinking -- but the ongoing damage to future generations will reveal this "wisdom" to be yet another step away from the beautiful relationship that God has created and defined so clearly."

And "Marriage is God's idea, not man's; therefore, He alone has the authority to redefine it."

Somebody needs to tell Albrecht that his god seems to have lots of weird ideas. For example, in Leviticus 19:19 god tells us that we can't wear clothes that have two different kinds of material. In Leviticus 20:18, we are told to deport any couple that has sex during the woman's menstrual period. Just because his god makes these weird demands, doesn't mean that they are binding on the rest of us.

Gentle readers of this blog, have you noticed the common thread running through all of Albrecht's rants? Yes, it is sex. The man truly hates it. He must really be obssessed with sex, considering how many of his published pieces deal with it.

So how did my neighbors elect this nasty bigot to Parliament?

Here's how: the Conservatives hid him from scrutiny. From the Record, January 20 2006:

Harold Albrecht, a Conservative running in Kitchener-Conestoga who is known for his views against gay marriage, was hustled away from reporters and into a banquet-hall kitchen yesterday where handlers refused to bring him out.

"He's in a meeting,'' a Tory official insisted, pushing a door closed as Albrecht stood next to empty dish racks.

In today's National Post Father Raymond J. De Souza claimed that Stephen Harper's "caucus is the most intellectually principled and serious in several generations". Albrecht's misrepresentations and bigotry, documented here, belie that claim.

For those who read our local paper, the Kitchener-Waterloo Record, Albrecht is infamous for a series of misinformed and nasty rants against sex and gay marriage. Here is a selection:

In an opinion piece published in the Record on October 29, 1993, Albrecht falsely claimed that "An analysis by researchers at the University of Texas estimates that when condoms are used, the risk of acquiring HIV from an infected partner is 31 per cent over a year's time. This study was reported in the Journal of Social Science and Medicine in June 1993."

Albrecht was evidently referring to this paper: Susan C. Weller, A meta-analysis of condom effectiveness in reducing sexually transmitted HIV, Social Science and Medicine 36 (12) (1993), 1635-1644. It's clear Albrecht never read the article, because he gets the title of the journal wrong: it's not the Journal of Social Science and Medicine, but simply Social Science and Medicine.

More importantly, Albrecht seriously misrepresented the conclusions of the Weller study. In the abstract, Weller concludes that "condoms may reduce risk of HIV infection by approximately 69%." A casual reader might think Albrecht is right, since 100% - 69% = 31%.

He's not. Albrecht is mixing up apples and oranges. The 69% figure of Weller represents the reduction in risk associated with using a condom. Let's say that the risk of getting HIV from an infected partner over one year's time without a condom is 10% (Weller's 1993 meta-analysis found figures varying from 4% to 19%). Then a 69% risk reduction means that with a condom, the risk of contracting HIV from an infected partner in one year decreases to about 3%. And 3% ain't 31%. Albrecht is either misinforming us, repeating misinformation, or innumerate -- not the best resumé for somebody headed to Ottawa to run things.