When I first moved to the UK, I hungrily watched the (orig. AmE) tv in my sublet apartment/flat in an attempt to acculturate myself. I can't remember if it was on an ad(vert) or on an early series of The Naked Chef, but I clearly remember the sentence:

Just bung it under the grill!

I already knew grill (=AmE broiler) from my time in South Africa. It was bung (meaning something like 'put forcibly, carelessly') that struck me. It seemed such an unattractive word, and yet it was being used about some food that was supposed to be wonderful after the bunging. Was this telling me something about British attitudes to food and cooking? Was it supposed to make the dish-making seem so sloppy anyone could do it? The questions clearly stuck in my mind, because the phrase has stayed with me for 25 years.

Bung was the first thing to come to mind when Maryellen Macdonald wrote to me:

You have a long post about cooking word differences, but I don’t think it contains a discussion of “add” vs. “tip”. US recipes say things like “add the carrots” to the pan, whereas UK recipes say “tip in the carrots”. My husband, the better cook in the household, asked me, “What do they mean tip the carrots? They’re cut up!” Hmm, maybe this little observation-ette isn’t quite sufficient for a post, but, perhaps you can use it somewhere.

I'm not sure which cooking-word difference post she was thinking of, since there are LOTS of them. But it made me think about "recipe verbs". Words like bung and tip are not necessarily cooking words—you can bung or tip a lot of things. But they are the kinds of words one finds in recipes or cooking programmes/shows.

I started asking my friends for other recipe-verb differences they had noticed. One friend (thanks, David!) pointed me to this parody cooking series, Posh Nosh, in which Richard E. Grant and Arabella Weir are minor aristocracy with an upscale restaurant brand. This particular nine-minute episode includes many great (fake) cooking verbs, instructing you to interrogate (clean?) then later to thrill open your mussels, to pillage some bones and to "gently gush [some AmE broth/BrE stock] until it completely obsesses the rice."

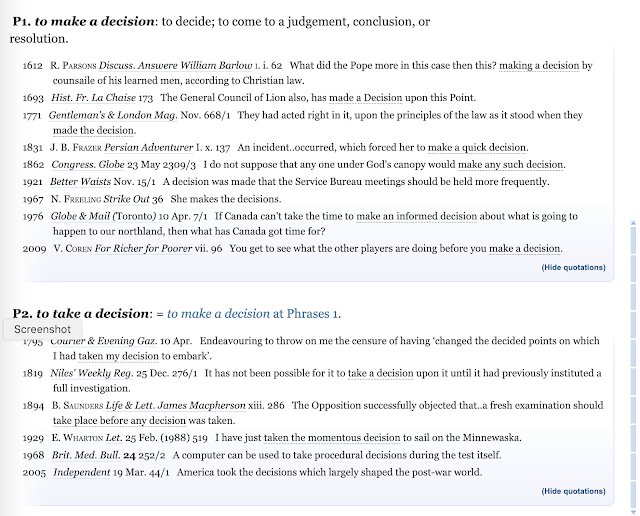

My friends weren't great at coming up with verb differences. (Several nouns were suggested.) Thank you to Ben, Björn, David, Jason, Michèle, Wendi for their suggestions. To complement these, I ended up doing an Advanced Search in the Oxford English Dictionary for region-marked cooking verbs. This post then got stupidly long and AmE biased; the OED is not good at marking words that are general to British English but not to North American.

For the following, I am marking things as AmE or BrE if either the OED or corpus results fairly firmly put the verb on one side of the Atlantic or the other. But you might know some of the "the other country's" words, especially if you ingest a lot of recipes and cooking programmes/shows. These things have been moving rapidly with mass media.

Some actual cooking verbs

- AmE broil v BrE grill is (part of) the topic one of my first blog posts. Also:

- AmE charbroil = cook over charcoal (not very frequent, more common in the modifier form charbroiled)

- AmE panbroil = cook [meat/fish] in pan with very little fat

- AmE grill v BrE toast comes up in a long post about cheese sandwiches (BrE toasties)

- AmE grill v BrE barbecue comes up in a post from the 4th of July

- orig. AmE nuke & zap: (informal) to microwave

- orig. AmE pot-roast: to slow-cook meat (esp. beef) in a covered pot/dish

- orig. AmE stir-fry (but this has been in BrE for most of your lifetimes)

- AmE plank: From OED: "Originally and chiefly North American. To prepare (meat, fish, etc.) by cooking it on a board over an open fire; (in later use) to cook on a board in an oven"

- AmE shirr: to poach (e.g. an egg) in cream rather than water. (I knew the word, but not what it meant!)

- orig. AmE flip: Not really a recipe verb, but...from the OED:

transitive. Originally and chiefly U.S. To cook (items of food) by turning over on a hotplate, grill, or griddle. Now typically with the implication that the subject has a job in a fast-food restaurant (chiefly in to flip burgers).

Some verbs that are often used to modify food words

- roast v roasted (of potatoes, chickens, etc.)—that post also mentions corn/corned beef, which has another post.

- skim v skimmed (of milk)

- minced/ground

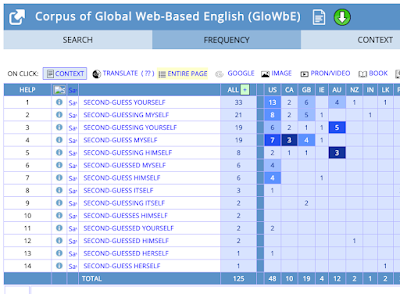

- mashed & smashed: I've written about mashed potato(es), which BrE can call just mash (now we're back into nouns). A related AmE verbal adjective is smashed. In the Corpus of Global Web-Based English (2013), North Americans have the collocation smashed potato(es); there are none in the British data. The distinction between mashed and smashed is that a smashed potato is less thoroughly mashed—it will still have some (orig. AmE) chunks of potato in it—and may well include the potato skins.

These days, you definitely see smashed on BrE menus—sometimes in front of potato but much more often in front of avocado. This Google ngrams graph shows that smashed avocado (blue line) surpassed mashed avocado (green line) in UK books around 2019, but the phrase has not taken off in the US (red line) in the same way, where people just talk about avocado toast without an adjective. (You hear that in BrE too, but it's not as prominent as in AmE.)

Verbs of placing

- BrE bung: to put forcibly, without delicacy. It's very informal word, but that goes with the vibe of a lot of British cooking shows. The closest equivalents are probably stick or throw (both General English), as in stick/throw it in the oven/pan, but bung feels the most informal and dismissive of the bunch. Here are some Google Image results for "bung it in the oven", which show the phrase applied to simple, quick recipes and the people who cook them:

- BrE tip in means, essentially 'pour in', but it's often used for solids. It can apply to chopped carrots, as in Maryellen's example, because you're assumed to be tipping the chopping board over the pan and 'pouring' the carrots in. The magazine that just came with my grocery order has tip in its first two recipes: bread dough is tipped onto a floured surface. Cooked spinach is tipped into a sieve.

- add: Mrs Redboots suggested this one. Add is General English, of course, but she notes a different usage:

American on-line cooks "add" ingredients to an empty pan. Can you add something when there is nothing there?

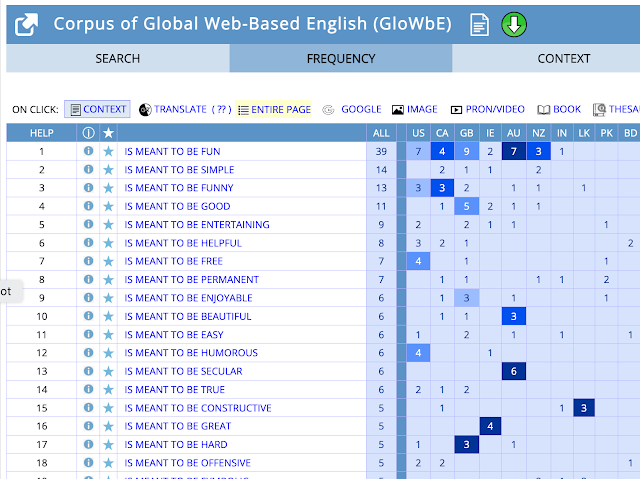

- pop: British people are always popping—popping in, popping out, popping to the shops—so I suspected that pop it in the oven would also show up as more BrE, but no. It looks like General English in the GloWbE corpus. Google Books has pop it in the oven becoming more common after the 1990s, with BrE use of the phrase overtaking American from 2014.

- AmE does seem to like to pop open various things, and BrE doesn't so much. This can include food/drink packaging (pop open a beer), but is often used of doors, the (BrE) bonnet/(AmE) hood or (BrE) boot/(AmE) trunk of a car, etc. Pop probably deserves it own post someday.

Verbs of mixing and cutting

- (BrE) blitz: It sounds a bit slangy, but blitz is nearly the standard verb in BrE for using a blender, especially for short blasts—to the extent that some people call any kind of blender a blitzer. (I did not succeed in finding out how common this is, because the data is overrun with people named Blitzer and sports blitzers, etc.). Blitz looks like it might be making it into US website recipes.

whisk: This is general English, but only in BrE (and rarely) have I seen it used to refer to the action of using an electric mixer (with whisk-y attachments). It's thus used a lot more in UK recipes.

a wooden reamer - beat [added 18 Mar 25]: I am looking at two cook(ery) books now, and see that Americans are always beating their ingredients where British bakers are whisking them. Neither word is particular to one nationlect, but the rates of usage seem quite different. (Click for an ngram of beat the eggs.)

- (orig. AmE) rice to press through a holey surface or mesh to create very small pieces; some people have special ricers for this. Especially used with boiled potatoes to make mashed potato(es).

- (AmE) pull: to "stretch and draw" a mixture (usually AmE taffy) until it is aerated and ready to set. OED has this as "chiefly" AmE.

And then there is the pull in pulled pork, pulled chicken, etc. OED has this as "chiefly U.S. in the late 20th century" (but it seems to have come back to the UK with US-style pulled pork). - (AmE) ream to juice a citrus fruit, using a device that you twist in the halved fruit.

Verbs of baking/pastry

- frost/ice: See this old post.

- (BrE) knock up (a crust): to seal and finish the crusts of a pie. (Here's an online discussion of it.) This is no doubt related to uses of the phrase in other crafts. Here's the first OED sense definition for knock up:

To drive upwards, or fasten up, by knocking; spec. in Bookbinding, etc. to make even the edges of (a pile of loose sheets) by striking them on a table; in Bootmaking, to cut or flatten the edges of the upper after its attachment to the insole.

AmE knock up is a more general expression for 'prepare quickly'. So if you knock up a pie (or a three-course meal or anything else) in AmE, that's talking about the whole process of preparing it, from start to finish.

- proof / prove In BrE, you prove dough and (traditionally) in AmE you proof it (unless you've watched lots of GBBO).

Verbs of preserving

- can v tin/bottle: Say you have tomatoes that you blanch and put into jars for use later in the year, in AmE that would be canning even though the tomatoes are going into a glass jar. You could also talk about canning if you were putting things in a jar to pickle, I think—it's just our general word for what to do when you have a glut of some fruit or vegetable that needs saving for later. The OED suggests tin (for putting things in metal containers) and bottle as BrE equivalents, but I think maybe for putting things in jars more general-English words like preserve and pickle might be more used? (Let us know in the comments.) Bottle would be used in AmE if you were putting things, like sauces or liqueurs, into bottles, but not usually for jars.

Verbs of meat preparation

- French: this one (not in my vocabulary) I got from the OED:

transitive. Cookery (now chiefly U.S.). To prepare a joint by partially separating the meat from the bone and removing any excess fat.

- tenderize orig. AmE, but has been in BrE since the 1970s