Fifteen months into his presidency, Donald Trump has been a failure in all but one area: the appointment of judges to the federal judiciary. The Senate has already confirmed 33 of Trump’s nominees to the bench; at this point in his first term, President Barack Obama had secured just 21 confirmations. These judges have life tenure, and if history is a guide, some of Trump’s judicial appointees will still be serving in 2070. No matter who controls Congress or the White House, these judges will be shaping the law for decades to come.

Given those stakes, it’s telling to look at a pair of opinions handed down by federal appeals court judges last week—one by a Trump judge, the other by a nominee of President Ronald Reagan. The first involves campaign finance, the second abortion. Yet both share a similar tone: flagrantly political, arrogant, self-righteous, and condescending. Taken together, these opinions illustrate the consequences of stacking the courts with ideologues.

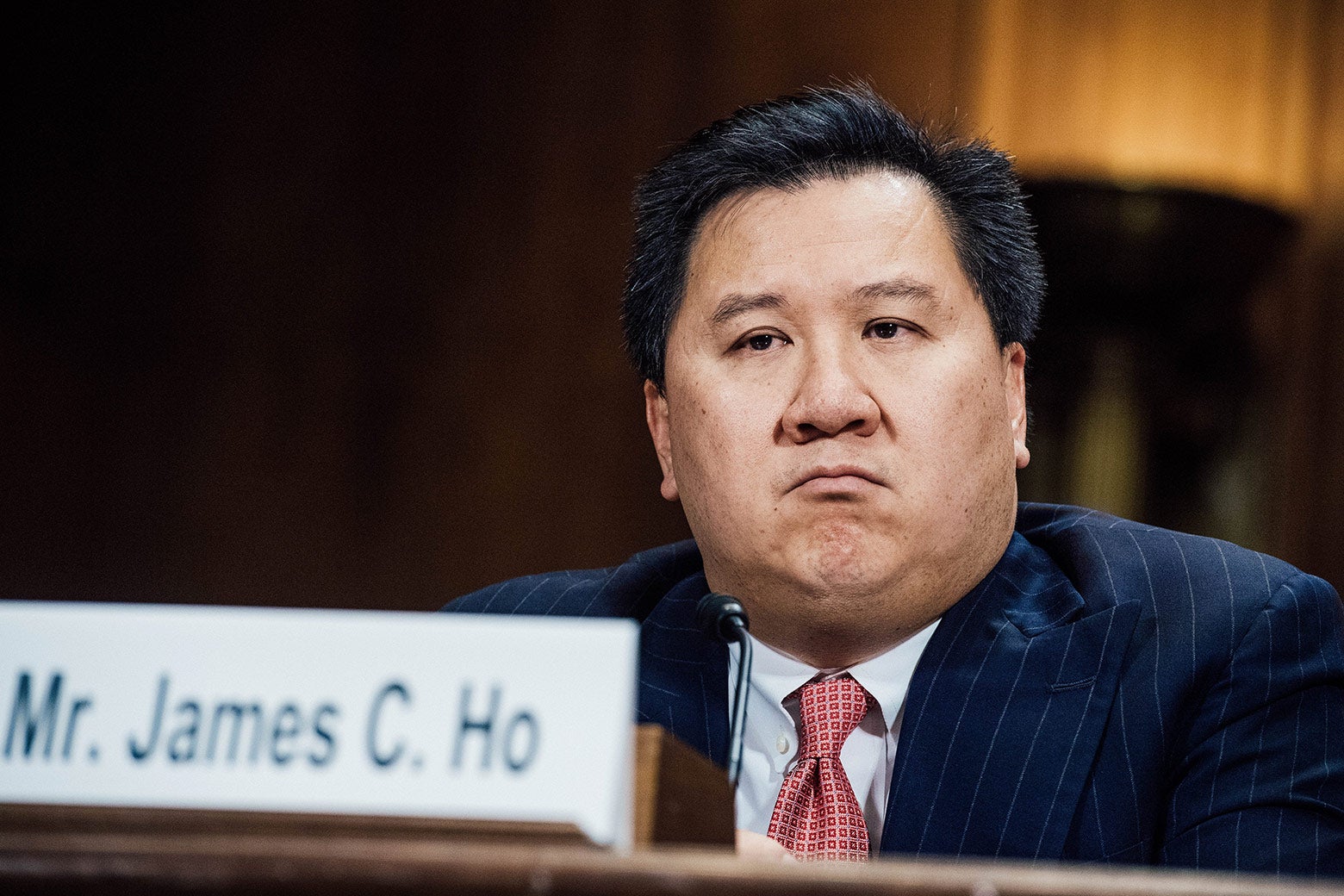

Start with last Wednesday’s opinion from Judge James Ho, whom Trump placed on the 5th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals. Unlike many of Trump’s judicial nominees, Ho is qualified for the job, with a long career in the law capped off by a stint as Texas solicitor general. If I were a senator, I would’ve voted for him. He was confirmed in December by a 53–43 vote.

Ho issued his very first ruling last Wednesday in Zimmerman v. City of Austin, which involves a challenge to Austin’s campaign finance law. The city prohibits individuals from donating more than $350 per election to mayoral and city council candidates. In February, a three-judge panel for the 5th Circuit ruled that this limit does not violate the First Amendment. The plaintiffs asked the full court to rehear the case en banc; by a 12–2 vote, it declined. Ho wrote a dissent from this decision, asserting that the court “should have granted rehearing en banc and held that the Austin contribution limit violates the First Amendment.”

That position is no surprise since Ho has previously argued that the United States should “abolish all restrictions on campaign finance.” What was startling was the petulant partisan tone of his opinion. Ho began by complaining about the “unfortunate trend in modern constitutional law” to “create rights that appear nowhere in the Constitution, but also to disfavor rights expressly enumerated by our Founders.” To prove this point, he cited Justice Clarence Thomas’ peevish opinion decrying the Supreme Court’s refusal to strike down a California law that requires a “cooling-off” period between gun purchases. Thomas complained that the courts are more eager to protect abortion access and same-sex marriage—which according to Thomas, deserve no constitutional protection—than they are to defend the Second Amendment. Right off the bat, then, Ho telegraphed his agreement with Thomas that gays and women have no constitutional right to individual autonomy.

It got worse from there. Toward the end of his opinion, Ho threw in a strange rant. “To be sure,” he wrote, “many Americans of good faith bemoan the amount of money spent on campaign contributions and political speech.”

But if you don’t like big money in politics, then you should oppose big government in our lives. Because the former is a necessary consequence of the latter. When government grows larger, when regulators pick more and more economic winners and losers, participation in the political process ceases to be merely a citizen’s prerogative—it becomes a human necessity. This is the inevitable result of a government that would be unrecognizable to our Founders. … So if there is too much money in politics, it’s because there’s too much government. The size and scope of government makes such spending essential.

This exaltation of “money in politics” is remarkably cynical. While the Supreme Court typically describes political spending as part of the right “to participate in the public debate through political expression,” Ho’s conception of campaign finance is transactional: He believes rich people may need to buy elections to protect themselves from regulations promulgated through the people’s representatives. While the Supreme Court describes campaign contributions as “participation in the democratic process,” Ho sees them as fundamentally anti-democratic—a tool the wealthy can deploy to buy off regulators. And if you don’t like sky-high political spending, Ho suggests, you should support deregulation, so powerful people and corporations don’t have to go through the trouble of purchasing elections in the first place.

This reasoning is drawn not from Supreme Court precedent or the Constitution, but rather Ho’s own views about the evil of regulations. When Ho does cite precedent, he uses it capriciously. To bolster his claim about the modern government being “unrecognizable to our Founders,” he cited the first Obamacare case, in which Chief Justice John Roberts voted to uphold the law. Ho seemed to ding Roberts for this move—a strange and irrelevant point to shoehorn into his ruling. Notably, Judge Edith Jones, who signed onto most of Ho’s opinion, declined to join this bit.

A day after Ho handed down his Zimmerman dissental, the 7th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals issued its decision in Planned Parenthood v. Indiana State Department of Health. That case involved Indiana regulations that barred women from terminating a pregnancy on the basis of the fetus’ sex, race, color, national origin, ancestry, or disability, including Down syndrome. Indiana compelled the abortion providers to tell women about this prohibition and required them to “bury, cremate, or entomb” all fetal remains.

Predictably, the 7th Circuit struck down these rules as a violation of Roe v. Wade and Planned Parenthood v. Casey, which forbid abortion restrictions that place an “undue burden” on women seeking to terminate. Judge Daniel Manion, a Reagan appointee, wrote separately to dissent from part of the ruling and bemoan the entire decision. “To put it mildly, this is an unfortunate case,” Manion began, declaring that it is “regrettable” than Indiana cannot “protect especially vulnerable unborn children.” He then urged the Supreme Court to overturn Roe and Casey, complaining that these precedents make abortion “the only true ‘super-right’ protected by the federal courts today.” Manion also criticized Democratic California Sen. Dianne Feinstein for calling Roe a “super-precedent,” citing a National Review article to rebut her. Then he attacked Planned Parenthood directly, writing:

Planned Parenthood and other supporters of abortion rights say that they are “pro-choice.” Yet they often challenge legislation simply intended to inform a woman’s choice. For example, the plaintiff in this case also obtained a preliminary injunction prohibiting Indiana from enforcing its requirement that a woman view an ultrasound at least hours before an abortion is performed unless she elects in writing not to do so. …

Indeed, Planned Parenthood and its allies have gone as far as to support California’s effort to force pro-life pregnancy centers to advertise for abortion. … If Planned Parenthood were really pro-choice (and not just pro-abortion), it would encourage a client who had initially been happy to be pregnant to seek counseling elsewhere when she discovered that her unborn child had Down syndrome or another disability. Such counseling with an informed advocate for the living fetus would benefit both the woman and her unborn child.

During oral arguments in the case, Manion acknowledged he got those ideas from observing his wife’s work running crisis pregnancy centers that attempt to talk women out of getting abortions. Later in his opinion, Manion cited studies showing that “people with Down syndrome and their parents and siblings are quite happy and lead fulfilling lives.” This proves, he wrote, that Indiana has “a compelling interest” in forcing all women whose fetuses have Down syndrome to carry these pregnancies to term.

The most frustrating aspect of Manion’s opinion is its dishonesty. He wrote that, currently, abortion is “more ironclad even than the rights enumerated in the Bill of Rights”—in fact, “the most favored right in American law.” That is nonsense. Dozens of states still force women to undergo anti-abortion “counseling” and an invasive ultrasound before terminating their pregnancies. States compel women to wait up to six days before obtaining the procedure and require providers to lie to their patients about “fetal pain” and the nonexistent link between abortion and breast cancer. Abortion is, in reality, one of the most excessively regulated constitutional rights in America—hardly “the most favored” of all the Constitution’s guarantees.

But Manion isn’t interested in facts. Like Ho, he wanted to editorialize about precedents he dislikes but has no power to change. And like Ho, he has virtually nothing to lose by doing so. Manion was confirmed in 1986 by a 50–49 vote, with then–Vice President George H.W. Bush breaking a tie. He will remain on the bench for as long as he wants. And he answers to no one.

Manion is 76 years old. Ho is just 45, and other Trump judicial nominees are in their 30s. These men and women (but mostly men) will be subjecting us to gratuitous screeds for much of the rest of our lives. They won’t always be in dissent: As Trump tips more federal appeals courts to the right, Ho and Manion will increasingly find themselves in the majority, turning their biases into law. For now, all Senate Democrats can do is take Ronald Klain’s advice: Read Ho’s Zimmerman jeremiad to every judicial nominee and ask them one simple question—is this really how judges are supposed to behave?