Owners' graffiti on pottery from Tissamaharama

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

Abstract

The legends on sherds from the archaeological site Tissamaharama in southern Sri Lanka are presented and their contents examined with regard to the composition of laypeople and Buddhist clerics from the late 3rd century BC onwards. The role of women is particularly noteworthy.

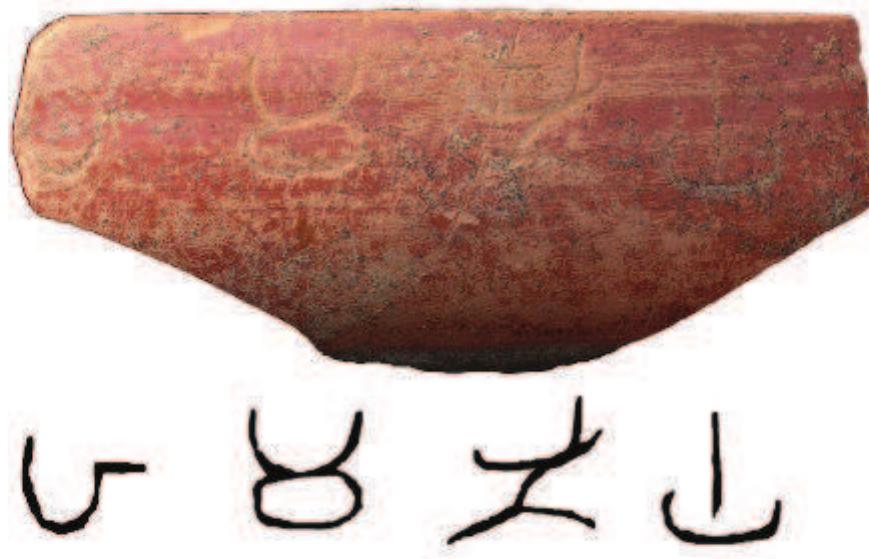

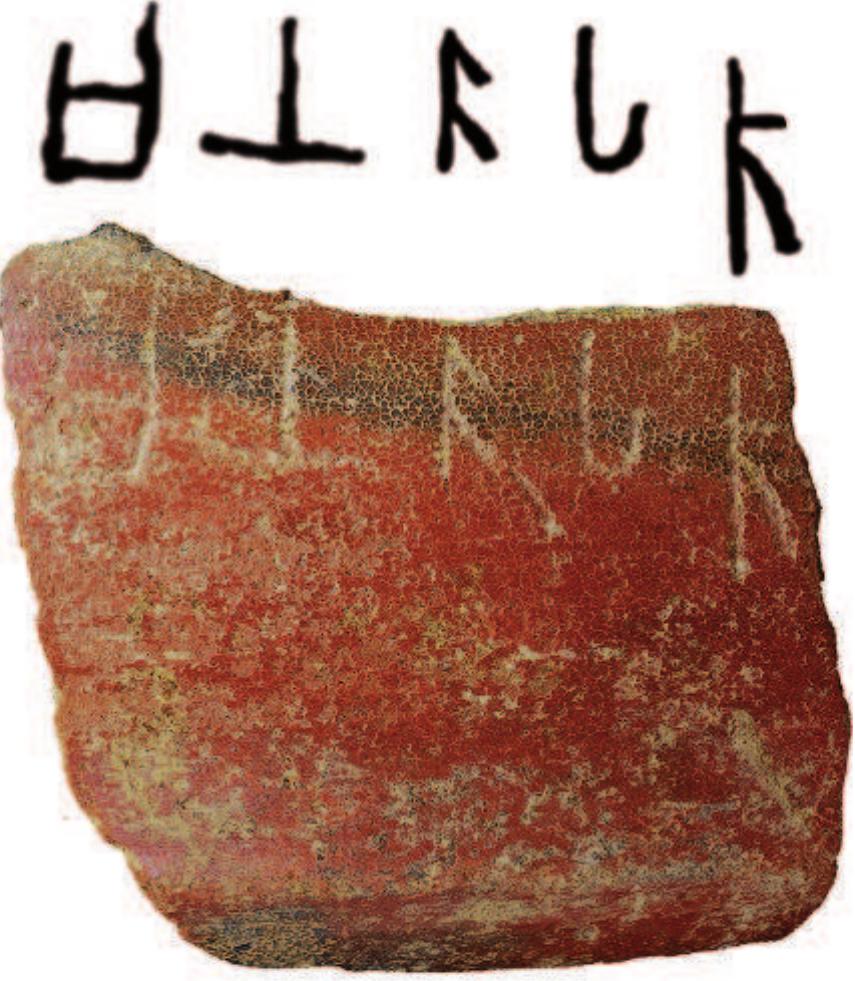

![Fig. 8. No.8, phase “b”, water-pot, Tissa Form D. Fig. 9. No.9, phase “b”, storage jar, Tissa Form E. The mi is disturbed in its lower left part. No. 9 (fig. 9). b2(k)[z]n1-Sa[ga] ///, “(Vessel for the com)munity of nuns”.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37180461/figure_008.jpg)

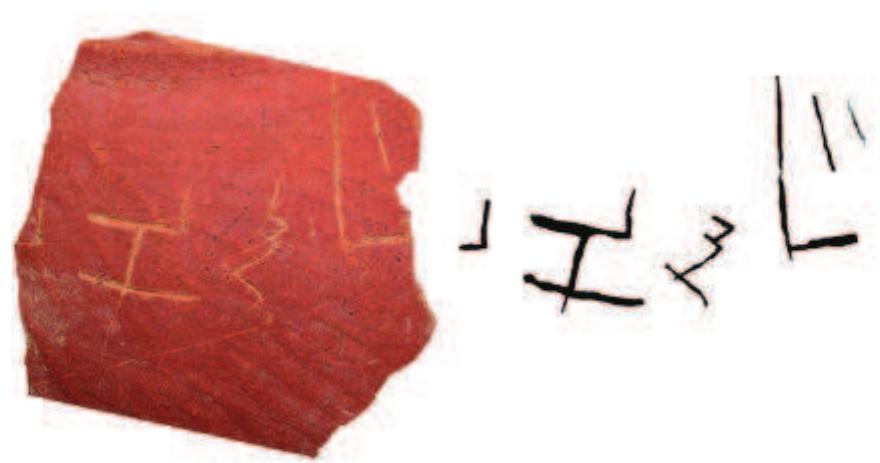

![No. 34 (fig. 34). pusa-sa[man]i ///, “(Vessel of the (novice?) nun Pusya”.](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37180461/figure_035.jpg)

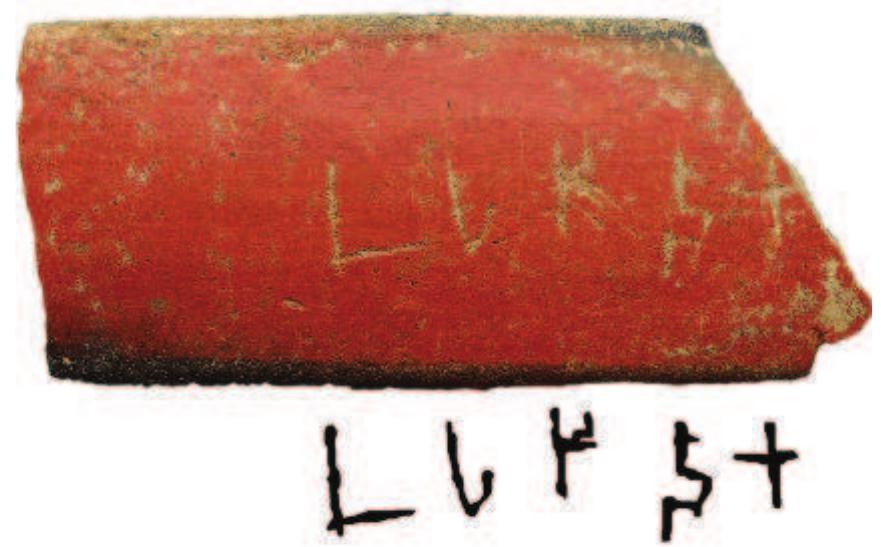

![No. 58 (fig. 52). <symbol> sumana[ha?] ///, “(Vessel) of Sumana”. The name, Skt Sumanas, is widespread and also found in Tissa-1 (1H,no. 18,23/93,16) reading <moon-symbol> <swastika> su[manasa].](https://figures.academia-assets.com/37180461/figure_052.jpg)

Related papers

Preliminary pottery sequence - First report Bibliography not included in pdf-file

A deposit of goddess plaques at Tissamahārāma – some preliminary considerations Zeitschrift für Archäologie Außereuropäischer Kulturen 3 (2010): 31–65 Abstract: During the 1996 excavation campaign at Tissamahārāma / Śrī Lankā a hoard of about 800 so-called goddess or Laksmī plaques were discovered inside a house erected on a brick-built fundament. There was no fi nd receptacle but the items lay strewn loose on the earth covering an area of c. 50 × 40 cm. The specimens were exclusively of the very small size type, which is scarce compared to the normal plaques of double height. Such a large number of small specimens in one hoard are unique for the ancient Ceylonese Fundlandschaft. Due to their outer appearance and the metrological data it becomes, again, evident that these objects are religious tokens and not coins. Evaluating all available information, we probably have to think of ritual downpour(s).

P. Calmieri / L. Colliva (eds.), South Asian Archaeology 2007. Proceedings of the 19th Meeting of the European Association of South Asian Archaeology in Ravenna, Italy, July 2007, Volume II. BAR International Series 2133, pp. 361-368. Oxford. , 2010

2020

This research is part of a wider scientific Italian-Indo project aiming to shed lights on pottery fabrication and trade circulation in the South India (Tamil Nadu region) during Early Historical Period. The recent archaeological excavations carried out in Alagankulam, a famous harbour trading with the eastern and western world, and Keeladi, the most ancient civilization centre attested in Tamil Nadu region, provided numerous fragments of archaeological ceramics, including fine ware and coarse ware potteries. Up to the typological studies, different classes of potteries were recognised, suggesting the presence of local productions and possible imports and imitations. Studied materials include common Indian products, i.e. black-and-red table wares and water jugs, along with red slipped wares, rouletted ware, northern black polished ware, which provenance identification is still debated in the current literature. In fact, for long time, the misattribution of several ceramic classes has...

Indian International Journal of Buddhism, 2018

This installment of my tripartite study of Esoteric Buddhism in the Sri Lanka of the late 7th through late 10th centuries focuses on two subjects. The longest section addresses the Abhayagiri's 'Mahanetraprasada' arama and its relationship to the mysterious Eye Relic during both the Esoteric Buddhist period as well as the Shravakayana restoration under the primacy of the Mahavihara. There is also an accounting of the vatadage sites, with particular emphasis on the vatadages at the Lankarama, the Ambasthala, and at Medirigiriya. Finally, there is an attempt to provide a conspectus on the present state of understanding of the practice and influence of Esoteric Buddhism at the Abhayagirivihara and affiliated monasteries, as well as an assessment of the role of Buddha Relics in the 'state protection Buddhism' of the Vajrayana as practiced by such figures as Amoghavajra and, apparently, the Abhayagirivasins. The Appendices are devoted to a close reading of the curious biography of Aggabodhi V and his association with padhanagharas and pamshukulika monks; a history of 80-year conflict between Rajarattha and the Cholas over the Pandya that serves as background for understanding the Abhayagiri regulatory inscriptions of Kassapa V and Mahinda IV; and a short chronology of the significant events during the last century and a half of the Anuradhapura period. This is a rather long paper (c. 270 pages) and the reader might benefit from the independent Table of Contents provided elsewhere on this site.

BEING THE SECOND PART OF AN INTERVIEW WITH PROFESSOR RAJ SOMADEVA PUBLISHED IN THE NATIONON SUNDAY, 16TH NOVEMBER 2014 Professor Raj Somadeva, PhD (Uppsala), Post Graduate Institute of Archaeology, Sri Lanka spoke to Darshanie Ratnawalli on a variety of topics, assiduously tackling all questions both verbally and in a 2400 word answer script, and modestly dismissing all thanks, citing his obligation to answer to the public. Here are excerpts from the interview continuing from last week.

Ancient Lanka

The Kuragala archaeological site is located in the Balangoda division of the Ratnapura district, southwestern Sri Lanka. This paper summarises archaeological investigations carried out in and around Kuragala indicating that human habitation in the region extended beyond 15,000 years into the past. Chronometric dating of the site and archaeological evidence show that Late Pleistocene and Early Holocene modern humans who followed a hunting and gathering subsistence pattern lived in this region. Archaeological finds and data from the Kuragala excavation include microlithic tools, bone tools, processed animal bones and beads, which indicate behavioural modernity among the inhabitants. This paper also discusses aspects of early historic occupation of the site based on the existence of human-modified drip-ledge caves and stone inscriptions. (Sinhala Article)

Chemical reviews, 2016

The control of luminous radiation has extremely important implications for modern and future technologies as well as in medicine. In this Review, we detail chemical structures and their relevant photophysical features for various groups of materials, including organic dyes such as metalloporphyrins and metallophthalocyanines (and derivatives), other common organic materials, mixed metal complexes and clusters, fullerenes, dendrimeric nanocomposites, polymeric materials (organic and/or inorganic), inorganic semiconductors, and other nanoscopic materials, utilized or potentially useful for the realization of devices able to filter in a smart way an external radiation. The concept of smart is referred to the characteristic of those materials that are capable to filter the radiation in a dynamic way without the need of an ancillary system for the activation of the required transmission change. In particular, this Review gives emphasis to the nonlinear optical properties of photoactive m...

Objective: To assess the prevalence of complete edentulism with respect to socio-economic factors and also its implications on treatment modality opted by the patients in urban and rural areas of Bhopal. Methods: A questionnaire survey was conducted on all patients and the data was subjected to suitable statistical analysis to arrive at conclusion. Results: On conducting a questionnaire survey it was found that a significant relationship exists between socio-economic factors and the implication of treatment plan opted by the patients. Conclusion: : Creating dental awareness among patients of lower socio-economic group and providing proper facilities at affordable rates encourages patients for undertaking timely treatment thus preventing consequences of edentulousness. Keywords: complete denture treatment, socioeconomic factor, epidemiological survey

2012

conducted the technical review of this document. Charles C. Monson (ISGS) worked with contributors and reviewers to assemble the report and prepared the Abstract and Executive Summary. David G. Morse (ISGS) led the effort to find a suitable injection site and all of the well drilling work to the casing point including the coring and open hole logging operations. Morse coordinated the Coal Characterization program and was the primary author for the coal characterization section of this report. Contributors to the coal characterization are as follows: ISGS contributors were Keith Hackley, gas chromatographic and isotopic characterization; and Christopher Korose, Geographic Information Systems and volumetrics. Laboratory experiments on coal adsorption, shrinkage, and swelling were conducted by Satya Harpalani, Southern Illinois University at Carbondale. Maria Mastalerz, Agnieszka Drobniak, and John Rupp (Indiana Geological Survey) were involved with planning, performed some desorption and gas chemistry and all maceral characterization analyses, and studied the roles of various coal macerals and coal pore size distribution in sequestration. Ivan G. Krapac (ISGS) coordinated the monitoring, verification, and accounting (MVA) program at the Tanquary site. He designed and developed the general MVA requirements of the site and worked with individual contributors towards the synergistic and collaborative effort of this program. Krapac coordinated, compiled, and edited the MVA strategy and MVA observations and discussions sections. ISGS contributors to both field efforts and data analysis and interpretation included Peter Berger (geochemical modeling), Gayathri Gopalakrishnan (GFLOW modeling), Keith Hackley (gas characterization), Donald Luman (color infrared imagery), Ed Mehnert (groundwater modeling, water well installation and development), and William Roy (geochemical modeling). Abbas Iranmanesh and Bracken Wimmer assisted with monitoring well installation and development, conducted the monthly water and gas sampling of the domestic and injection site ground water and the injection coal seam monitoring wells, and contributed to documentation of sampling methodology. ISGS well drilling crew led by Jack Aud installed groundwater monitoring wells. Bob Butsch (Schlumberger Carbon Services) completed the cased hole log analyses. Scott Frailey led the pilot planning, scheduling, and logistics of implementing the plan through post-carbon dioxide (CO 2) injection testing and ultimate abandonment of wells and reclamation of the site. Frailey designed the pressure transient tests and performed real time analyses of the data. He coordinated the numerical modeling and pressure transient analyses for analyzing the pressure and injection rate from the CO 2 and water injection periods. Frailey was the primary author for the introduction and sections on site selection; pilot site design modification and well arrangement; drilling operations, open hole tests, and casing; completion; coal seam (in situ) characterization (pre-CO 2); field observations during active CO 2 injection; interpretation, analyses, and modeling of pilot results; and conclusions. Text for these sections was also contributed by

Geological Society, London, Special Publications, 2009

2018

I would like to first say a very big thank you to my supervisor Dr Katrin Mueller-Johnson for all the support and encouragement she gave me, both during the journey that was my PhD and during the detour I took in South Africa to pursue a small dream that will hopefully turn into a research career. Without her guidance and feedback this PhD would not have been achievable. Danke! I gratefully acknowledge the funding received towards my PhD from Gates Cambridge. The scholarship has not only supported me throughout my PhD, but also during maternity leave, which is far from self-evident, even in 2017. Thank you for supporting women who pursue both a career and a family. A very special thanks goes to my fellow Gates Scholars. Being part of this community has inspired me in unimaginable ways. Thank you all for showing me that you should always follow your heart and that you can achieve anything if you just set your mind to it. Without your inspiration I would not have volunteered in protected areas in South Africa and thus found a way to combine my passion and my work. Thank you also for fighting battles with me and help dust off some of the patriarchal structures. And finally, thank you for walking with me along the way.

2019

The electron’s orbital distance, ionization energy and shape can be modeled based on classical mechanics when the recently-discovered pentaquark structure is used as the model of the proton. This paper accurately models atomic orbital distances based on this five-quark structure of the proton, in which the orbiting electron is both attracted by an anti-quark and repelled by quarks in the proton. The orbital distance is classically defined as the point where the sum of the forces is zero, removing the need for a separate set of laws in physics, known as quantum mechanics, to describe the electron’s position in an atom.

King Edwin's Palace, Old Yeavering, Northumberland: Archaeological Evaluations, 2012-2013, 2014

I)scriptioni anid Classificationi of Historical Ceramiics 19 Sources for Ceramnic Identtificationi 201 l)escriptive anid Classificatory Systemis 20) Chroniological Placemnitt of Ceramic Types or Site Assemlblages 25 Backmnarks 25 Other IDatitig Methods 28 Cultural Genecralizationis 28 Methods Used ini Anialyzinig Ceramnics fromn the Cannton Region 29 3 The Ceramic Classification 31 The Hierarchical Systemi 31 Tranisfer Prinitinig 33 1 kcaliiig 36 Edge I)coratioii 36 Notiraiscd/H-aiidpainitcd 41 No lDecorationi Except Body Moldinig 46 Undeccorated 46 Mappini-M utrphy (l're-1I84(1 IDeposit) 47 Mappini-Murphy (Ouitside the Pre-184() Deposit) 48 Mappinl-Vauighni 52 Saitmil H. Smnith 5 4 1 i ar \-, 'I o rdani 58 ,)IiL:I-(()IICVe 62 5 Summary and Conclusions 67 Classification anld Chronology 07 Trade anid Transportation 69 Material Culturc mnd Indications Of Status: Ca. 1 830-60) 71 Appendix 1 75 31td earls sveiitit-eiiturv Lceramics f .rom ive Nites Basetd oin our pterusal of asseniiblages from tother excavatka vA\Jtld bv the Caiiioii Project.)tice I of the ccl sites ill MIiSSOUri anti neighboring states, as well as of Aiilvsis \vaN to Olrg~anizet tile kcraiiits Inito chi-'s aildt to colltCtioiIS tConIplete vessels, We have fount coinsiderkoii pare tlit po.rceiitaigts of like' classtes oil .ii iiircrsitt' able similarities Ill composition. Thus wec believe the baisis. SIome pre\vioiN stutdies of historical ceramics havte rt-port is applitcable to a large setctioni of the Midwe,,st. To 'Itto:ilipiel to liiik ceraliic typtes or classes to wetalthl ai. illustrate the range lin mlaterials weC tise tolor plates inl Status, espeCi-all I' Ill Iiistanict's svllert the absolute or addith ut to black-anti-w.hite line tdrawiings. This sh1ould relative v.tilts Of (crtaili ccrimnie types or classes arc atdt to thle uIsefLmieSS of the report. kiiowii [aniL-iitr\ tiata, agricultural census tiata. antd Steveral people tieserve: acknowlt'tlgment for the tconahitt'etu ruIal vksis off rtsid~ttial structurt's al]\C lo tti us Ibutions thtev ii ,de tdurinig tht' various phases tof the ito railk-I rtltr 1% %\e CIth 111,111 v c-olomists of theC SaIlt R ivter projec t. Siiitt its Intctptioni. Pal R. I. Hennling, f'Oriltrlv valleyv froluticr. giving uis a) ~ood baisteliine against whilch of thlt UnIivtrsitv oif Nebraska-Linicoln., andt now of' to conipare the ceram ic asst'ublages. Ltuthter (C XIlege. I)eelrall. Iowa, ha~s serveti as prinicipal Astomiti. pterhaps inore si giliit'cait. gol f t.t tl vstigtir (of thet (ann. :I Pro ect. He has allowt'd uts project w\as to prodtuce a tleai led tiescriptiol (if' tlit unli iiiteti Lit itutie ii tetloping new rescart'l imtert'sts nllto.rii Is. framing it ii a tclassificationi svstim that miuti has provitdtt a steatd\ haiid throughout thet projet-t. wouldl be applicable across tht' Midwest. One problemi Terr': Norris, Otitr liasoi wvith the St. Louis D istrict. t'ilcouiitt'retl Iv reseairchers working oil niitlwtsterii U.S. A nh v Corps oif Luigititers. anidt Owen I utt. chief' histmIriti sites is, teLit'lck of publishted illustrations of' of tlt hivironiiital Setittoni of'that of'ficte, havte offcrt'ti 'Bi shcrds into vessels was provided by Michael K. Trimble. mia,. O'Bri Jeffrey Yclton identified several backmarks andJames C.

Harry Falk

Harry Falk