Struggle for Survival: Case of Veddas Culture in Sri Lanka

…

266 pages

1 file

Sign up for access to the world's latest research

AI-generated Abstract

The paper explores the plight of the Veddas, an indigenous community in Sri Lanka, highlighting their struggle for survival amidst a globalized world that threatens their cultural heritage. As part of a larger initiative by the SAARC Cultural Centre focusing on diminishing cultures in South Asia, this study emphasizes the vulnerabilities of smaller cultural groups that lack market value and are at risk of being overshadowed by dominant cultural forces. Through the presentation of specific case studies, the paper aims to raise awareness about the preservation of these cultures and the importance of supporting their existence.

Figures (31)

Related papers

https://saarcculture.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/2011_vol_2.pdf, 2011

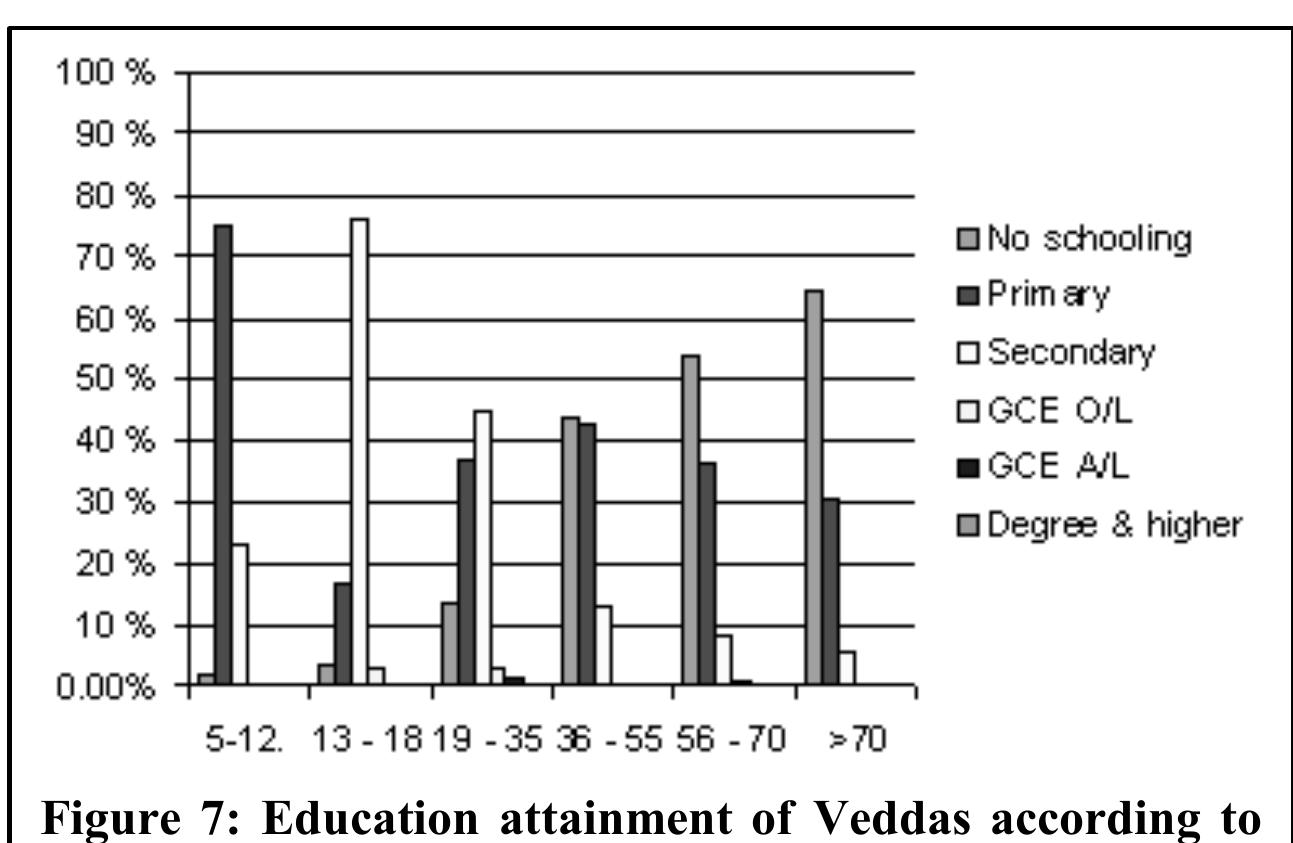

Veddas, an aboriginal group of Sri Lanka have survived for several millennia by adapting and coping with external stresses imposed on them. They were inhabitating the island long before the arrival of Aryans and had spread all over the island. Currently they are facing stresses that threaten to modernize them which could easily result in vanishing them as cultural group. They have been struggling for the survival of their ‘traditional lifestyles’ which is threatened by of hegemonic Sinahala, Tamil and Muslim communities of the country as well as the process of globalisation. This paper focusses on the current status of Vedda community particularly their socio-cultural life. Adopting qualitative and quantitative analysis on the nature of use and disuse of cultural activities of the Vaddas, the paper concludes that unless speedy holistic action is not taken, there is always a chance for the Vedda as a community to become only an episode of the history within a generation or two.

Special project courses cover topics not otherwise covered by general education courses and other courses in the catalog for the discipline. These courses require direct experience and focused reflection in an in-depth study of a specific discipline topic and/or the critical analysis of contemporary issues in the discipline. They are targeted to self-selected students with an interest in the subject matter and involve active participation. The course delivery incorporates an experiential component of no less than 30 percent but not to exceed 70 percent. This experiential component may include field studies, interdisciplinary learning and/or the practical application of discipline-related concepts, theories, principles, and methods with a specific focus. All courses require an orientation session to deliver academic and experiential information (syllabus, academic requirements, field preparation, logistics, etc.) (3 credit hours) DuPage -Social/Behavioral Sciences and the Library Department of Anthropology Summer Semester 2024 2 A. General Course Objectives: 1. Demonstrate knowledge of special topic presented in course. 2. Analyze current trends and research regarding the special topic presented in this course. 3. Compare and contrast different perspectives on discipline-related information to those presented on this special topic. 4. Explain the relationship of this selected topic to the main body of knowledge in the discipline. 5. Demonstrate ability to work independently on a discipline-related topic.

I 954, authorized the Director-General (Resolution 4.3 I) "to organize or encourage with the assistance of M e m b e r States and their National Commissions . . . . studies and roundtable discussions concerning the development of the cultural life of the communities ". . . Accordingly, UNESCO included in its programme for 1955-56, a series of University seminars and field studies in-South-East Asia to assess the present state of their traditional cultures.

Social Anthropology, 2005

Mountain Research and Development, 2009

The Highlander Journal, 2023

Reworking Culture is based on the author’s ethnographic engagement with people in and around the village of Sadolpara in the West Garo Hills in highland Northeast India (HNEI), where he conducted more than 20 years of fieldwork. It cunningly deals with the broader anthropological question of what ties people to the place they live in, in an attempt to critically explore the concept of ‘cultural identity’ from emic perspectives. To de Maaker, the idea of community, much like ‘culture’, becomes manifest in the sustained enactment of mutual relations that people continuously create, maintain and transform through everyday interactions and in response to material conditions and political and economic opportunities. By carefully examining such nuanced networks of sociality, the author showcases the dynamic of Garo village life.

SAARC Cultural Centre, Colombo, 2015

Online International Interdisciplinary Research Journal, 2019

People and culture are inseparable since there is no denying the fact that what makes any human society is its culture; a Latin word which was derived from “colore” meaning to practice or cherish. For a society to be societal, it must be cultural, therefore, society and culture are also intertwined. The culture of any society is the way of life of its members; the collection of their ideas and habits which they learn, share, and transmit from one generation to the other. In fact, culture is a blueprint for living held by members of a particular society. Tribals are grossly endowed with rich and unprecedented cultural values with which harmony, solidarity, orderliness, sanctity and sanity are ensured within their community. Despite the fact that there were no trained and armed security officers in the olden days as we have today, yet their communities were void of chaos. In view of this, this paper is set to examine some of these tribal cultural values and how the force of modernity has influenced its observance with a particular reference to the Nyishi tribe of Arunachal Pradesh. An attempt also will be made to discuss the concept of modernity and equally on how tribal cultural values were enforced in the traditional societies. In conclusion, recommendations will be made on the need to revive the tribal cultural values as a panacea to the high level of moral decadence in the contemporary tribal societies.

Reworking Culture: Relatedness, Rites, and Resources in Garo Hills, North East India , 2022

Reworking Culture: Relatedness, Rites, and Resources in Garo Hills, North-East India provides intimate insights into the lives of hill farmers and the challenges they face in day-to-day life. Focusing on the ongoing reinterpretation of traditions, or customs, the book critiques the all too often taken-for-granted assumption that upland societies are unchanging, characterized by cultural homogeneity and strong internal cohesion. Based on extensive ethnographic fieldwork, the book focuses on a rural area where a substantial number of people practice the traditional Garo community religion. The book does not aim to document and idealize relics of cultural practices destined for extinction in the face of greater forces such as globalization. Yet it does ask why people continue to be committed to practices that are considered obsolete elsewhere in the same region, given that over the last century and a half the vast majority of the Garo have abandoned the community religion in favour of Christianity. The book explores the creation and continuing reinterpretation of the multiple relationships through which people are connected to one another, as well as to their environment. Far from being immutable, these relationships need to be constantly expressed, enacted, and (re-)interpreted. Reworking Culture shows how what people perceive as tradition, is continuously revised and reworked in response to new economic and political opportunities, as well as to changes in the ontological landscape.

Annuaire Roumain d’Anthropologie-Journal, 2011

"The paper tries to explain the adaptive practices of Sugali tribe of Andhra Pradesh, South India. In the process of adaptation, Sugalis experienced various social, cultural, and economic systems and how these systems have altered their traditional institutions which are vis-à-vis related to existing livelihood patterns are probed empirically. These are further gave a way to analyse and address inter-linking concepts and terms related to traditions which are directly or indirectly related to Sugalis. The influence of outside culture brought a major change in their societal set-up. Thus, we look at Sugalis as a community with heterogeneous characteristics and experienced all these inter-linked and intra-linked changes in their life courses. Thus cultural effects on them made to invent new ideas which lead to further complicated and still marginalized and under-privileged. Key Words: Sugali, Livelihoods, Adaptations, Traditional Institutions, South India"

De Silva Premakumara

De Silva Premakumara