THE ORIGINS OF

PHARYNGEALIZATION

IN SEMITIC

PETR ZEMÁNEK

enigma corporation, Ltd.

Praha 1996

�The Origins of Pharyngealization

in Semitic/

Petr ZEMÁNEK

- Prague : enigma corporation, Ltd. 1996

(Prague : T.R.S. Polygrafické služby)

ISBN 80-9010704-3-9

Published by

enigma corporation, Ltd.

P.O. Box 308

CZ 111 21 Praha 1

© 1996 by enigma corporation, Ltd., Prague

© 1996 by Petr ZEMÁNEK

All rights reserved, including those of translation into foreign languages. No part of

this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or

mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Printed in the Czech Republic.

ISBN 80-9010704-3-9

�CONTENTS

Contents . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . i

Acknowledgments . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ii

Abbreviations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . iii

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1 Characteristics of emphasis . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.1 Characteristics of pharyngealized articulation in Arabic . . . . . . . . .

1.2 Characteristics of glottalized articulation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3 Characteristics of individual emphatic consonants . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.1 Emphatic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.2 Uvular q . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.3 Emphatic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.4 Emphatic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.5 Emphatic . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1.3.6 Other emphatic phonemes . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2 The relation between pharyngealization and glottalization . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1 Analysis of the alternations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.1 Emphatic and its alternation with voiced d . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.2 Uvular q and its alternation with voiced ğ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.1.3 Emphatic and its alternation with voiced z . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2 Analysis of the control set: Phonetically conditioned doublets . . .

2.2.1 Emphatic and its alternation with non-voiced t . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.2 Uvular q and its alternation with non-voiced k . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.2.3 Emphatic and its alternation with non-voiced s . . . . . . . . . .

2.3 Analysis of the control set: Phonologically and phonetically

non-related doublets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3.1 Doublets with the alternation of b / r . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

2.3.2 Doublets with the alternation of / ġ . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3 Summary and conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.1 Evaluation of the sets of alternations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.2 Phonetic environment of the alternations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.3 Semantic distribution of the alternations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.4 Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

3.5 Model of the development of pharyngealization in Arabic/Semitic

4 Supplement: Lists of doublets . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

References . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

1

3

4

6

7

7

9

11

12

13

13

16

20

20

24

29

32

33

36

39

41

42

44

46

46

49

50

50

54

55

81

t̄

ṫ

ḋ

ṡ

ż

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

�ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The present study is an attempt at the explanation of the origins of the pharyngealized articulation in Arabic and Semitic and is a culmination of several years

of work, although many times interrupted. The interest in this type of articulation

was inspired already during my studies in the beginning of eighties by Professor

PhDr. Karel PETRÁČEK, CSc., who also guided me through the first steps in the

study of this phenomenon. I am glad to get the opportunity to express my gratitude

for his teachings and his inspiring ideas.

Through my work at this study, it has been at various stages consulted and

discussed with several scholars, who have contributed in important ways to the

growth of my knowledge and understanding at different stages of my journey.

These include notably Arne A. AMBROS, Michael G. CARTER, Ladislav DROZDÍK,

Jaroslav OLIVERIUS, Zdena PALKOVÁ, Stanislav SEGERT and Petr VAVROUŠEK.

Needless to say, none of these scholars are to blame for any errors that remain

in the work.

Finally, I owe my thanks to James LANCASTER, who willingly corrected my

English. I know that I have surely missed mentioning others who truly deserve

inclusion here, and to them I apologize most deeply.

�ABBREVIATIONS

AION

ArOr

BSOAS

C

GLECS

JAOS

JCS

JNES

JQR

LAR

LIQ

MSA

OA

R1(2,3)

SON

SV

V

WZKM

ZA

ZDMG

Annali di Istituto Orientale Universitario di Napoli, Napoli.

Archív orientální, Praha.

Bulletin of School of Oriental and African Studies, London.

consonant, consonants.

Groupe linguistique des études chamito-sémitiques, Paris.

Journal of the American Oriental Society, New Haven.

Journal of Cuneiform Studies, Baltimore.

Journal of Near Eastern Studies, Chicago.

Jewish Quarterly Review, London, Leiden.

laryngeal, laryngeals.

liquid, liquids.

Modern Standard Arabic.

Oriens Antiquus, Roma.

the first (second, third) radical of the root.

sonant, sonants.

semivowel, semivowels.

vowel, vowels.

Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes, Wien.

Zeitschrift für Assyriologie und Vorderasiatische Archäologie,

Berlin, New York.

Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Wiesbaden.

�Characteristics of emphasis

1

Introduction

One of the characteristic phonological features in Arabic, but also in majority

of other Semitic languages, is the so-called "emphatic" series. From the articulatory point of view, it is, especialy in Arabic with its dialects, a bunch of

various types of co-articulation. Under the heading "emphatic" we usually understand pharyngealized1 or glottalized consonants.2 Roughly it can be said that the

former are found in Arabic and Modern Aramaic (Neo-Assyrian, cf., e.g., HOBERMAN 1988 or TSERETELI 1982), the latter in the Semitic languages spoken in

Ethiopia. In all of these languages, since they are still living ones, with the exception of G c z, we have direct evidence on the phonetic realization of these consonants, while in case of other Semitic languages the character of the articulation

can differ. Traditionally, it is the pharyngealization that is ascribed to most of the

dead Semitic languages. Modern Hebrew constitutes a special example in this

respect because of cultural influence that results in de-emphatization in the pronunciation of originally emphatic sounds.

From the phonetic point of view, a lot of studies state that this correlation

exhibits considerable growth, especially in the modern dialects of Arabic. It

should be pointed out that this growth does not in many cases mean the growth of

number of pharyngealized consonants, but various types of co-articulation, like

labialization, (strong) nasalization, etc. This is, e.g., the case of emphatic b (labia˙

in

lization) or the case of emphatic (nasalization). These issues will be treated

detail further on in the following part of this study.

However, there are still some aspects of this co-articulation feature in Arabic

and Semitic languages that are not completely clear. The discussion on the origin

and type of development of this correlation is still going on. The aim of present

study is to investigate exactly these two aspects and attempt at a proposal of the

development of the phonological feature of "emphasis" in Arabic and Semitic

languages. The study tries to contribute to the discussion on which coarticulation

of emphatics, i.e. glottalization and pharyngealization, predates the other. It is

based on data collected from the dictionary of Arabic (KAZIMIRSKI 1860), and the

data are evaluated from statistic, phonetic and semantic points of view.

The concept of emphatics in this study is mainly based on TRUBETZKOY’S

analysis of co-articulation (Nebenarbeitskorrelation, 1939:122 ff.). The approach

ee

ṅ

1

Instead of the term pharyngealization, one can meet terms like velarization (e.g., OBRECHT

1968) or, rather rarely, uvularization (DOLGOPOLSKY 1977).

2

In Semitic, especially post-glottalized ejectives.

�2

Petr ZEMÁNEK

to the phonological system used in this study proceeds from the non-statical,

dynamic conception of the system, as given especially in the study of the phonological system of Czech by J. VACHEK,3 together with the reflexion of these concepts in the work of K. PETRÁČEK (1971, 1975, 1990:142-159 and 247-290). The

terminology used in this study corresponds mainly to the one used by ESSEN

(1979).

3

Dynamika fonologického systému současné spisovné češtiny [The Dynamics of the Phonemic System of Contemporary Literary Czech]. Praha 1968.

�Characteristics of emphasis

3

1.0 Characteristics of emphasis

Let us first try to resume the situation of the "emphatics" in Semitic:4

ḋ

7

t̄

9

ḋ

ṗ

ṡ

ˇ

l̇

(

ṙ

ż

ḋ

ḋ

k̇

ż

ḋ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

ṗ

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

q

ˇ

q

ż

ṡ

ċ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

Akkadian5

Eblaite6

Ugaritic

Hebrew

Syriac

Sayhadic8

G c z

Arabic (Classical)

Neo-Assyrian

Modern South Arabian11

)

10

ee

In all the Semitic languages, there are at least three of them: , and q,12

which holds especially for the Ancient Semitic languages. This could point to the

ṡ

ṫ

4

If not quoted differently, our data are taken from MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:43-45.

5

For Akkadian, cf. JUCQUOIS 1966:264-266; for the problem of the original articulation cf.

KNUDSEN 1961.

6

The situation in Eblaite is not completely clear. KREBERNIK 1982:179 and 1983 passim

postulates 4 emphatic phonemes, which are nevertheless not attested in the texts. His analysis

offers reconstruction of the system, graphical manifestation of the phonemes in the texts is

nevertheless heavily dependent on the possibilities of the cuneiform writing. DIAKONOFF

1984:4 characterizes these phonemes as non-voiced - cf. also the use of the symbol z for

non-voiced "emphatic" phoneme in Ugaritic - e.g. GARR 1986, SEGERT 1984, etc.

˙

7

In the ugaritological literature, this phoneme is represented as z - cf. e.g. SEGERT 1984,

KTU 1976 passim etc.; for discussion see e.g. VOIGT 1990 etc.

˙

8

Old Epigraphic Southern Arabic. The name Sayhadic is used according BEESTON 1981.

9

For the characteristics of this phoneme, cf. RODINSON 1981, VOIGT 1990, etc.

˙

10

The last two mentioned sounds function rather as variants, cf. reading of Quran, articulation of wa-llāhi, bi-llāhi etc. For more details, cf. e.g. PETRÁČEK 1952, FERGUSON 1956,

AMBROS 1981. For possible emphatic r already in Classical Arabic cf. SCHAADE 1911.

˙˙

˙˙

˙

12

i.e. mehri, š e ri, soqotri etc., languages spoken in Yemen.

ḣ

11

Including q, which is nevertheless a little bit problematic from the point of view of modern

Semitic, e.g. Arabic.

�4

Petr ZEMÁNEK

fact that the emphatic sounds in older phases were non-voiced, which is also the

way the proto-Hamito-Semitic phonological system is reconstructed.13

In the West Semitic (i.e. Arabic, Hebrew, Syriac, Ugaritic and Neo-Assyrian)

the emphatic consonants are pharyngealized, in Ethiopian Semitic (here represented by G c z), they are glottalized. For Akkadian, there is at least a possibility that

the emphatic sounds were glottalized (cf. KNUDSEN 1961), and Modern South

Arabian probably stands in the borderline between glottalization and pharyngealization.14

In the following, we will characterize the pharyngealized and the glottalized

ways of articulation:

ee

1.1 Characteristics of pharyngealized articulation in Arabic

The characteristics of emphasis in Literary Arabic, from the synchronic point

of view, is not connected with special difficulties. Articulatorily, it is characterized

by the raising of the dorsum to the back part of the velum (GAIRDNER 1925), by

slight backing of the typical dental and alveolar articulatory position to the rear.15

They are produced with a primary constriction involving the tongue tip and blade

in the anterior region of the oral cavity, and a secondary posterior-inferior movement of the back of the tongue into the pharynx region. This secondary movement

may be accompanied by a lateral spreading of the tongue dorsum thus creating a

more hollow configuration.

Accoustically, as shown in OBRECHT 1968, the main characteristics is the

lowering of the second formant (F2), which can be in some cases considerable.16

OBRECHT also points to the fact that the velarization17 is the most effective in

13

Cf. e.g. DIAKONOFF ET AL. 1987:12, where the following emphatic phonemes are reconˇ c,

ˆ k, kw, x, xw.

structed: ṗ, t, c, c,

˙ ˙

14

Cf. NAUMKIN & PORKHOMOVSKY 1981:9 for Soqotri, where they describe a free variation

of pharyngealization and glottalization.

˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙

15

ALI & DANILOFF 1972 give the following values: s is shifted to the back for 2.89mm when

compared to s, for t/t the difference is 2.76mm.

˙

˙

16

OBRECHT 1968:24-26 gives the following types of differencies in F2: t/t - 1800/1200 Hz;

d/d - 1750/1050 Hz; s/s - 1500/1050 Hz; z/z - 1500/750 Hz. From the point of view of the

lowering of F2, the values for opposition of k/q are very similar to the ones given above 2100/1200 Hz.

˙

˙

˙

˙

17

The term "velarization" was later on replaced by "pharyngealization", which, at least in

Arabic, is more exact.

�Characteristics of emphasis

5

influencing neighbouring sounds - both consonants and vowels. It induces a

tongue backing gesture on adjacent sounds, much more clearly than pharyngeals.

A little bit more problematical is the characteristics of emphasis in the dialects of Arabic. In most of the dialects, the emphasis covers much more consonants than in Literary Arabic. Especially the Maġrib dialects exhibit a high

degree of emphasis in their phonological systems. E.g. ZAVADOVSKY 1981 in his

analysis of Mauretanian dialect stated that each consonant can have its emphatic

and non-emphatic variant.18 Such a situation lead some authors to distinguish

between emphatisant and emphatisables.19 Nevertheless the degree of emphasis

is dependent on further criteria. It is not always the pharyngealization that is gathered to the new emphatics in the Arabic dialects, they are sometimes characterized

differently. E.g. emphatic b is rather characterized as labialized than pharyngeali˙

zed, emphatic and as strongly

nasalized (MALAIKA 1959), etc.

It is surely also the phonetic nature of the feature in question - i.e. the pharyngealization - that leads to the rise of further emphatic phonemes in Arabic. This

can be observed even in Literary Arabic, where we can mention e.g. the assimilation t > , t > etc. at the VIII verbal stem. The pharyngealization can

further effect on the consonants in the non-contact position - cf. GAIRDNER

1925:51, and sometimes it is the whole word that is considered "emphatised" - cf.

D. COHEN 1969:63-6, BANI YASIN & OWENS 1987:303 etc. Also phonetic studies

show that the pharyngealization can considerably affect its neighbourhood. Some

remarks can be found by OBRECHT 1968; the studies of GHAZELI 1981 and HAMDI

1990 must also be mentioned. The first states that the effect of pharyngealization

does not pass beyond the boundaries of a syllable, the second claims that according to his measurements the pharyngealization can spread over the syllable boundaries, but only towards the end of the word (i.e. progressive, not regressive

spread). It seems that this situation is caused mainly by phonetic-articulatory

ṅ

ṁ

ṫ ḋ

ḋ

ṫ ṫ

ṫ

18

A similar situation is also described by BANI YASIN & OWENS 1987:303-5 for Jordanian

dialect, where the authors allow for the possibility that each phoneme has its emphatic

counterpart. Nevertheless, as independent emphatic phonemes they name only the following:

d, t, s, m, l, g, b, w.

˙ ˙

19

The terminology was adduced by D. COHEN 1969, based on HARRELL 1957:69ff where in

his analysis of the phonological system of Egyptian colloquial Arabic, where he speaks about

primary emphatics (i.e. t, d, s, z), secondary emphatics (i.e. r, l, k, b), that occur quite rarely

and mostly in words where primary emphatics occur, and marginal˙ emphatics (g, f, t, h, ġ,

˘

h, n, w, y, ’) - i.e sounds, where there is phonetic possibility of emphatizing these phonemes,

but there are no minimal distinctive pairs. HOBERMAN 1988 and 1989 gives also phonemes

that stop the spread of emphasis, i.e. phonemes that cannot be emphatised.

˙ ˙ ˙ ˙ ˙

˙ ˙ ˙

¯

˙ ˙ ˙ ˙

�6

Petr ZEMÁNEK

reasons, i.e. the articulatory organs that are in a specific position remain in such a

position even after the articulation of the pharyngealized sound.

Such a situation clearly leads to attempts to create another concept of emphasis, i.e. a concept connected not only with one phoneme but with a higher unit syllable or even word. From 1942 we have an attempt to characterize emphasis as

a suprasegmental feature - the study by Z. HARRIS on Morrocan Arabic. From this

study, there were several similar attempts suggesting a similar solution, e.g.

ZAVADOVSKY 1981, etc.

Apart from purely linguistic criteria and arguments it is possible to adduce

also other criteria that can shed further light on the role of emphasis in the Arabic

dialects. This feature has been used also as a criterion for socio-linguistic study

(ABD-EL-JAWAD 1986), but also in other studies we can find remarks on stylistic

"deemphatisation" (KHALAFALLAH 1969:30) and the use of emphasis can also be

determined socially - the younger and more educated the speaker is, the lower

degree of emphasis used.20

1.2 Characteristics of glottalized articulation

Under glottalized sounds various types of sounds have been understood:

ejectives, implosives, creaky or glottalized vowels, pre-glottalized continuants etc.

For the Hamito-Semitic languages, the ejectives and implosives are the most

important. We can find implosives in Chadic (b’, d’ and y’) and post-glottalized

ejectives especially in Cushitic languages, but they occur in other groups of

Hamito-Semitic as well. In the frame of Semitic, the area with the greatest spread

of glottalized sounds is Ethiopia, where in the Ethio-Semitic the glottalized sounds

may have emerged or preserved due to the areal influence of the Cushitic languages. Other area, where glottalized articulation alternates with the pharyngealized one, is the Southern Arabia, in Modern South Arabian, i.e. Mehri, Š ri

and Soqotri. All of the glottalized sounds attested in Semitic are ejectives.

These facts mean that for the purpose of this work we can basically limit our

scope to ejectives, i.e. eggressive post-glottalized consonants, since these represent the main articulatory manner in Semitic.

Ejectives are produced with egressive pharynx air. The larynx moves upward

with the vocal cords closed during the articulation of the consonant, which creates

air pressure in the pharynx. After the release of the consonant articulation, the air

e ḣ

20

E.g. BANI YASIN & OWENS 1987:304 in note 8 mention that the lowest degree of emphasis is in the category 30-45 years of age, with university education - 81% of non-emphatic

variants. The use of emphasis is also determined sexually - women use less emphasis than

men.

�Characteristics of emphasis

7

from the pharynx creates an egressive air stream originating from the pharynx. We

can find glottalized plosives (p’, t’, k’) and glottalized affricates and fricatives (č’,

c’ ~ s’).

It should be noted that it is physiologically impossible to produce other than

voiceless ejectives, since the glottal closure does not allow participation of the

voice. On the other hand, implosives, which are attested in Chadic languages, tend

to be voiced (cf. WEDEKIND 1990:128). Another point which is important for

Semitic languages is that, according to WEDEKIND (1990:128) languages tend not

to use the difference between a glottalized affricate (such as c’) and a glottalized

fricative (such as s’) for phonemic contrast. This might help in explanation of the

articulatory character of the Semitic a de.

ṡ

1.3 Characteristics of the individual emphatic consonants in Arabic

As the basis of our analysis we include among the emphatic consonants the following five phonemes: , , , and q.21 In addition, we will comment on the

phonemes that can be emphatic or emphatized, but do not appear in the MSA.

These phonemes can be traced especially in the dialects of Arabic or other Semitic

languages. The phonemes that appear as emphatic in the phonological systems of

other Semitic languages are discussed briefly in the review of other Semitic

phonological systems.

ż

ṡ

ḋ

ṫ

1.3.1 The emphatic

The explosive unvoiced alveolar is in Arabic situated in the center of the

Arabic emphatic sounds (mu b aqa - cf. SIBAWAIH 1889, D. COHEN 1969 etc.) and

is attested in Literary Arabic as well as in almost all the dialects of Arabic. The

exception here is the situation in the peripheral Arabic dialects (Malta, Arabic

dialects in Central Asia, Arabic dialects in Africa - Sudan, Chad, Kenya etc.). In

case of African dialects, this phoneme is substituted by its glottalized counterpart cf. e.g. ZELTNER & TOURNEAUX 1986 as an injective for the Arabic dialects in

Chad. A similar situation can be found also in the Upper Egyptian dialects - cf.

KHALAFALLAH 1969:30. Exceptionally, it is also possible to find it realized as the

implosive d’ (in the dialects in Algerian Sahara - J. OWENS, personal communication).

A close connection between the glottalized t’ and pharyngealized is shown

also by the perception similarity of the two sounds - cf. FRE WOLDU 1984-86 and

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

21

This phoneme is not always included among the emphatic phonemes.

�8

Petr ZEMÁNEK

1988.22 The possible alternation of these two types of articulation is also attested

by the data from Soqotri, where these two forms are perceived as allophones (cf.

NAUMKIN & PORKHOMOVSKY 1981:9-10).

The data in FRE WOLDU 1984-86 and 1988 also show that this phoneme is

most probably the connecting bridge between the glottalized and pharyngealized

way of articulation. This phoneme in Sudan is the only one that allows the twofold

articulation and both articulations are considered acceptable.

Although is attested in all the Semitic languages, its articulation in various

languages can be different. In all the Ethiopian Semitic languages it is realized as

glottalized, the same is the situation in South Arabian and Neo-Assyrian. It is

reconstructed for Akkadian, too, where it has been mostly represented by the

grapheme for d. The reason for this might be caused by the shortcomings of the

cuneiform writing as indicated by MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:31. Nevertheless, the

choice of d might be caused also by other reasons. Our opinion is that analogically

with the situation of the glottalized k’ (q) in Akkadian (cf. KNUDSEN 1961) the

emphatic was in Akkadian realized as glottalized, or its graphical representation

can reflect the processes of the transformation of the glottalized articulation into

the pharyngealized one. In case of Hebrew and other Canaanite languages, the

situation is not completely clear as far as the manner of articulation is concerned,

and we are still unable to decide which manner of articulation was the one used.

Outside the Semitic languages, in the Hamito-Semitic languages, we find this

phoneme only in the Cushitic and Omotic languages, represented as the glottalized

t’ (EHRET 1980 and BOMHARD 1984 for the Cushitic languages, BENDER 1975 for

the Omotic). For Chadic we find it only in the reconstruction of STOLBOVA 1986

for Western Chadic, in the actual systems it is not attested (NEWMAN 1977 and

JUNGRAITHMAYR & SHIMIZU 1981 do not reconstruct this phoneme even for

Proto-Chadic). In their reconstruction we find only voiced implosives. In Berber

we find it only in the reconstruction of Proto-Berber (PRASSE 1972), APPLEGATE

1970:592-3 classifies emphasis in Berber as a suprasegmental phoneme,23 which

would reflect a situation similar to the one in modern Arabic dialects or Modern

ṫ

ṫ

22

In these two studies, FRE WOLDU examines the perception similarity of pharyngealized and

glottalized consonants in Tigrinya and Sudanese Arabic. In the perception test with the

Sudanese speakers, the glottalized t’ is perceived as an acceptable articulation of pharyngealized t.

˙

23

Emphatic consonants are treated there as a sequence of a consonant and an additional

feature of pharyngealization. This additional feature is phonemic, but its ___domain is bigger

than the consonant (syllable, CV, etc.) and it has been found to affect nearly all of the

consonants of the phonemic system.

�Characteristics of emphasis

9

Aramaic. The realization of the emphatic sounds in Berber is pharyngealized. For

Egyptian it is reconstructed in the protosystem only by RÖSSLER 1971, whose

reconstruction is nevertheless motivated by an obvious effort to postulate a clearly

symmetrical system. The reconstruction of the emphatic series is based only on

analogy with other series (voiced and non-voiced), i.e. analogically to the phonological systems in Semitic languages. No other analysis of Egyptian phonology

includes emphatic .

As we have seen, although this phoneme is not present in a number of actual

systems of the Hamito-Semitic languages, it is reconstructed for almost all the

protosystems (Semitic: MOSCATI ET AL. 1964, BOMHARD 1988, etc., Cushitic:

EHRET 1980, Omotic: BENDER 1975, Chadic: STOLBOVA 1978, 1986, Berber:

PRASSE 1972, etc.) and similarly, it is reconstructed for the Hamito-Semitic (Afroasiatic) system (cf. DIAKONOFF 1988:34 ff., 1987; BENDER 1975, BOMHARD 1984,

HODGE 1987pr. etc.). The reconstructed manner of articulation is the glottalized

one.

ṫ

1.3.2 Uvular q.

Explosive non-voiced q is usually included by the old Arabic grammarians

among the emphatic consonants, though not in their center (i.e. mu b aqa), but in

the mustacliya set. This phoneme is not always taken into consideration when

studying the emphatic consonants. The reasons why we include it in our analysis

are historical and systematic. We are aware of the fact that in case of articulative

definiton of the emphasis (i.e. pharyngealization in case of Arabic) this phoneme

would have to be excluded from the analysis. The features of this phoneme rank

it rather with the back consonants (even pharyngeal - cf. DELATTRE 1971) rather

than with the pharyngealized ones.

This phoneme is without doubt one of the most interesting phonemes of the

Arabic phonological system. This is i.a. proved by the rich bibliography connected

with this phoneme and its problems. The realization of this phoneme in Arabic can

be very different (especially in Arabic dialects, but the differencies are tracable

even in MSA). In Arabic, it can be realized in the following way:24

ṫ

- q - non-voiced uvular (CANTINEAU 1960:68; HARRELL 1962:5; DIEM

1972:9, etc.)

24

On the other hand, there is also some evidence for other phonemes that are realized as q cf. the situation in Mauretania, where h (non-voiced velar fricative) is realized as q (WILLMS

˘

1972:1).

�10

Petr ZEMÁNEK

- g - voiced palatal (CANTINEAU 1960:68; ZAVADOVSKY 1962:7; DIEM

1972:9, etc.).

- ’ - glottal stop (GAIRDNER 1925; FEGHALI 1919:25; CANTINEAU 1960:68,

etc.).

- ġ - voiced velar (postvelar) (CANTINEAU 1960:68, etc.).

- k - non-voiced palato-velar, e.g. in Maltese (COHEN 1970) and other peripheral dialects of Arabic (e.g., HEINE 1982, OWENS 1985, etc.

- ğ - voiced affricate, e.g. in Iraqi Arabic - šarğı̄ for šarqı̄ - eastern.

CANTINEAU 1960:68 differentiates the realization of this phoneme between

the sedentary population25 (q, , k, ’ - i.e. as a non-voiced consonant) and bedouins (ġ, g, ğ, ǵ - i.e. as a voiced consonant). On the other hand, the different

articulation can be based on other factors, too. This phoneme is used as a criterion

for sociolinguistic studies (cf. e.g. ABD-EL-JAWAD 1986, ROSENHOUSE 1984,

etc.).

According to GHALI 1983:436 q in most Arabic dialects has a very low

functional load, nevertheless, such a situation may be caused by the above mentioned variety of articulation of this phoneme.

In Classical Arabic, it is sometimes characterized as voiced (cf. medieval

Arabic grammarians, e.g. SIBAWAIH, ZAMAHŠARĪ, cf. also SEMAAN 1968). Today,

˘

in MSA it is realized as non-voiced postvelar

or even more often, as uvular (cf.

AL-ANI 1970, GIANNINI & PETTORINO 1982:9 etc.).

Non-voiced explosive q is attested in all the Semitic languages (MOSCATI ET

AL. 1964:44 and 45 table). The differences are in the realization of this phoneme in a number of languages (Ethiopian, South Arabian, Modern Neo-Assyrian) it is

realized as glottalized. Its articulation in the dead languages is not completely

clear, there are indications, however, that point to the glottalized articulation (cf.

KNUDSEN 1961, BOMHARD 1988:115-116 - both authors study the influence of

glottalization and pharyngalization on the neighbouring vowels, non-voicedness

of the emphatics in Akkadian and the application of the Geer’s law (GEERS 1945).

The pharyngealized articulation would be then limited to Arabic and most probably also to Canaanite languages. This region, together with Arabic, seems to be

in case of emphasis the innovative area.

k̇

25

i.e. especially in the villages, the situation in the towns can be different.

�Characteristics of emphasis

11

1.3.3 Emphatic

The voiced explosive i s in Arabic traditionally included among the emphatic sounds. Its articulation is given in KÄSTNER 1981 and AL-ANI 1970. In some

regions of the Arab world it merges with emphatic (Iraq, Tunisia, etc.).

In many studies, it is possible to find this phoneme listed as a member of the

Semitic protosystem (cf. e.g. BROCKELMANN 1908:43, also MOSCATI ET AL. 1964

as ) , but as early as by VILENČIK (1930:89ff) we find another position. MARRASSINI (1976:337) speaks on the delicacy of the problem of the classification of in

Proto-Semitic, cf. also RODINSON (1981). In other Semitic languages it is not

possible to find the phoneme in all the systems, and furthermore the correspondences with other Semitic languages show the possibility that this phoneme might

have another type of co-articulation than pharyngealization (cf. M. COHEN

1931:10; MARTINET 1953:72 etc.). Also the correspondences with other HamitoSemitic languages (cf. DOLGOPOLSKY 1983:130-31 for Cushitic, BALDI 1987pr.

for Hausa, CONTI 1976 for Egyptian) offer a different picture. The phoneme in

loanwords and correspondences is often realized as l or d (in Hausa and other

Chadic languages also as implosive d’).

The situation in G c z shows that in graphical representation the phoneme

was differentiated from . RODINSON 1981, based on further data, speaks about a

lateral character of this phoneme, i.e. not about emphasis understood as pharyngealization or glottalization. A similar situation is found in Arabic dialects (GAIRDNER 1925:20, RABIN 1952:33, CANTINEAU 1960:54ff., 284ff.; D. COHEN

1963:11, COLIN 1930:92, 101-4 etc.), in the articulation of some Coranic reciters

and in Modern South Arabian languages (Mehri, Š ri, Soqotri - BROCKELMANN

1908:132), where the phoneme is realized as l. Besides these data, there is also a

correspondence with ld - loanwords from Arabic in Spanish - a - a yca > aldea, alqā ı̄ > alcalde (RODINSON 1981:103), in Maltese with l - ri ā > rela, rama ān >

ramelan etc. (COLIN 1930:101). Today the lateral character of is rarely doubted,

though sometimes the phoneme is characterized slightly differently - as cacuminal

(MARRASSINI 1976:337), and generally the as an emphatic (i.e. pharyngealized

or glottalized) is not included into the Semitic protosystem. Cf. also HODGE

1983:149 in the Hamito-Semitic (Afroasiatic) context.

Nevertheless it is not possible to exclude definitely the connection of and

the sibilant series. This idea has appeared already in VILENČIK 1930 and BLAKE

1946, and the combinatorics (incompatibility) also show that this phoneme preserves almost completely the incompatibility with sibilants and not with l, as might

be supposed on the basis of its possible lateral character. There are also a number

of doublets of this phoneme with lateral ś that are mentioned in KURYŁOWICZ

1973:28, STEINER 1977 (passim) and FISCHER 1968:59-60. One of the best anaḋ

ḋ

ż

d̄

ḋ

ḋ

ee

ṡ

e ḣ

ḋ

ḋ

ḋ

ḋ

ḋ

ḋ

ḋ

�12

Petr ZEMÁNEK

lyses known to us is VOIGT 1991, where the phoneme is included to the protosystem as lateralized sibilant ś. From such a position even the most peculiar correspondences can be explained.26 That is why our position is that should be

classified in the Semitic protosystem as a lateralized member of the sibilant series.

ḋ

1.3.4 Emphatic

In Arabic, from the first attestations by the Arabic grammarians (SIBAWAIH,

HALĪL - cf. ROMAN 1977, etc.) this sibilant is put among the emphatic sounds, i.e.

˘

pharyngealized

(the so-called mu b aqa) series. It is one of the phonemes that

appear as pharyngealized in all the Arabic dialects in the role of "emphatisant".27

It is attested in all the Semitic languages with the exception of Neo-Assyrian

and some Arabic dialects that have lost the emphatic series (Malta - D. COHEN

1970, Chadic Arabic - ZELTNER & TOURNEUX 1986, ROTH 1979, Arabic pidgins

in Sudan, Kenya and Nigeria - e.g. OWENS 1985:233-4, HEINE 1982 etc.). In older

works the supposed articulation is pharyngealized, in recent studies other solutions

are offered (cf. VOIGT 1986, STEINER 1982, CLAASSEN 1971, CARDONA 1968

etc.). In other languages, where we have the possibility to see the phonetic realization, is realized in a different way. In Modern Hebrew it is realized as affricate

(c) and this usage prevails today even in liturgical praxis with Biblical Hebrew. In

Modern Ethiopian languages it is realized as c, in G c z it is usually characterized

as emphatic. Also in Modern South Arabian we can see a tendency towards an

affricated realization of this sound (both articulations, i.e. pharyngealized and

affricated, are considered equal - MILITAREV, personal communication). Outside

the Semitic languages we find one indirect indication for an affricated realization

of this sound - in Old Egyptian it corresponds with the phoneme (i.e. ğ in Semitistic transcription) - cf. CONTI 1976, which might reflect a correspondence of a

nonvoiced (c) and voiced (ğ) affricate. Cf. also GARBINI 1972 and 1984.

Beside this manner of articulation, in some works it is possible to find attempts to characterize the original articulation of this phoneme as glottalized (s’ cf. ROMAN 1990 etc.). ROMAN 1981-2 characterizes the sound as "pseudoglottalized", and the position of VOIGT 1986 is similar.

ṡ

ṫ

ṡ

ee

d̄

26

Cf. the correspondences with q in Aramaic (Arabic ’ard-un - Aramaic ’arqā - the earth)

and correspondences with s in a number of languages, e.g. Hebrew ’eres - Arabic ’ard-un the earth.

˙

˙

˙

For terminology, cf. COHEN 1969.

˙

27

�Characteristics of emphasis

13

Interesting data is found in Yemen, where this phoneme in some dialects can

be realized as st (BEHNSTEDT 1986:5-9). A similar situation can be found also in

loanwords in Arabic - cf. lat. castra > qa r - D. COHEN 1962:120.

As far as its position in the protosystem is concerned, it seems that it should

be classified as a glottalized affricate or fricative.28

ṡ

1.3.5 Emphatic

The articulation of this phoneme in Classical Arabic places the phoneme

clearly among the pharyngealized emphatic consonants (cf. SIBAWAIH). It is

articulated as voiced pharyngealized alveolar spirant or interdental ( - AL-ANI

1970:48 etc.). The Arabic pharyngealized explosive often merges with this

phoneme in the dialects of Arabic, e.g. in Iraq, Tunisia etc. In Classical Arabic, its

functional load is minimal (cf. HERDAN 1962:54 - only 0,6%) to such a degree that

for the majority of the roots with it is hard to find minimal correlation pairs.

In other Semitic languages, this phoneme is attested only scarcely, MOSCATI

29

ET AL. 1964:43-5 mentions it only for Arabic and Epigraphic South Arabian.

The grapheme transcribed as in Ugaritic represents an unvoiced phoneme (cf.

MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:43, VOIGT 1991 etc.).

Outside the Semitic languages this phoneme can be traced only in Berber (cf.

WILLMS 1972 and WOLFF 1981:177), where it is possible to expect the influence

of Arabic. In every other family of the Hamito-Semitic languages this phoneme is

not attested.

Sometimes this phoneme has been postulated for the Proto-Semitic phonological system - cf., e.g., MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:24. On the other hand some authors

speak about this phoneme as an innovation in the Arabic system. Cf. e.g. GARBINI

1972:42 (footnote 1), PETRÁČEK 1981:165 etc., who speak of an innovation in the

Amoreic and especially the Arabic area (cf. also LOPRIENO 1977:135).

ż

d̄

ḋ

ż

ż

1.3.6 Other emphatic phonemes

The five above mentioned phonemes occur in Classical Arabic (and also

MSA). Nevertheless the number of emphatic phonemes in the dialects of Arabic

is much higher. Especially in the "central" Arabic dialects30 the correlation of

28

Note that according to WEDEKIND 1990:128 it is not necessary to distinguish between

fricative or affricate character of this type of ejectives, since languages tend not to use this

opposition for phonemic contrast and the two types can easily be variants of one phoneme.

29

Sayhadic in BEESTON’s terminology - BEESTON 1981.

30

In the so-called peripheral Arabic dialects, the emphasis is mostly lost.

�14

Petr ZEMÁNEK

emphasis developed considerably. There are dialects where we can find an emphatic variant of every phoneme (e.g. in Mauritania - cf. ZAVADOVSKY 1981, Morrocco - cf. HARRELL 1965, Jordan - cf. BANI YASIN & OWENS 1987, etc.). In

studies on such dialects we meet the idea of conceiving the emphasis as a suprasegmental phoneme.

The occurrence of additional emphatic phonemes in other Semitic languages

is rather rare. MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:43-5 does not mention any other emphatic

phonemes, SWIGGERS 1981 adduces emphatic ˇ for Mehri and Š ri. Within the

framework of glottalized phonemes, it is possible to find glottalized ṗ and č (NeoAssyrian - TSERETELI 1978:34-8, G c z - e.g. VOIGT 1989:634 etc.).

As far as the Hamito-Semitic languages are concerned, several other emphatic phonemes are postulated. The largest number can be found in the reconstructions of DIAKONOFF (1988, 1984, 1987 etc.) - ṗ, , , ˇ , , q˘h, w. In actual systems

of the Hamito-Semitic languages we find pharyngealized phonemes in Berber,

non-voiced ejectives in Cushitic and Omotic and implosive sounds in Chadic (b,

d, y). Generally the character of the original emphatic phonemes is postulated as

non-voiced, only in Chadic do we find voiced implosives and in Berber voiced

pharyngealized consonants.

The situation in Arabic is rather different. Already in Literary Arabic (MSA)

we find certain tendencies towards the expansion of the pharyngealized type of

articulation (emphatic - cf. PETRÁČEK 1952, FERGUSON 1956, etc.), also the

possibility of velarization/pharyngealization of r (> ) in Classical Arabic - cf.

SCHAADE 1911:14-16. In the Arabic dialects, the growth of this correlation becomes considerably dynamic. From the point of view of emphasis we can divide the

Arabic dialects into two groups - to the peripheral dialects, where the emphasis

does not grow or decreases - dialects in Malta (D. COHEN 1970), in Central Asia

(G. TSERETELI 1956), in Africa (ROTH-LALY 1972, HEINE 1982, OWENS 1985

etc.), the second group is formed by the central dialects, where the pharyngealization increases very dynamically. Here, in fact, are all the Arabic-speaking

countries. It seems that in the Arabic Maġrib (especially in Morocco and Mauretania) the dynamics of emphasis is so high that it covers the whole phonological

system - cf. especially ZAVADOVSKY 1981.

Even more "emphatic" sounds can be found in Neo-Assyrian, where the

expansion of "emphasis" is the highest of all the Semitic languages (cf. TSERETELI

1982, HOBERMAN 1988 and 1989 etc.). Emphasis is nevertheless treated differently in those studies: it is not connected with the individual emphatic phonemes,

but is considered as a so-called suprasegmental feature, or, as in HOBERMAN 1988

and 1989 in the framework of so-called autosegmental phonology.

e ḣ

k̇

ṡ

ee

k̇

ṙ

ċ

ċ

ṫ

l̇

�Characteristics of emphasis

15

Nevertheless, from the articulatory point of view, under so-called "emphasis"

we can find very different types of articulation. Apart from emphatics from Classical Arabic, which are pharyngealized, we encounter labialized (b, etc.), and stro˙

ngly nasalized ( , - MALAIKA 1959) consonants.

It is clear that the number of "emphatic" consonants in the modern dialects of

Arabic is growing, on the other hand, it is also clear that not all of them can be

covered by pharyngealization. It seems that in this case use of a more general term

like co-articulation or secondary articulation would be more suitable.

ṅ

ṁ

�16

Petr ZEMÁNEK

2. The relation between pharyngealization and glottalization

2.0 In all reconstructions of the Hamito-Semitic phonological system the connection between glottalization and pharyngealization is widely accepted. Both types

of articulation are taken as two realizations of the co-articulation (Nebenarbeitskorrelation, cf. TRUBETZKOY 1939, PETRÁČEK 1988:32-4, 1990:284-290).

As has been observed several times, the emphatic phonemes in Semitic are

generally realized by two basic ways of articulation, i.e. as pharyngealized and

glottalized.31 The problem of which of the two articulations was the original one

appeared relatively early, and during the discussion the question has been solved

in different ways,32 however, recently the opinion that the glottalization is the

original way of articulation in proto-Semitic is gaining ground. This can be seen

e.g. in recent reconstructions of the proto-Semitic and proto-Hamito-Semitic

(Afroasiatic) phonological system,33 where the emphatics are reconstructed as

glottalized and voiceless.

The relation between glottalization and pharyngealization is confirmed also

in studies by FRE WOLDU (1984-6, 1988), which show a certain auditory similarity

between glottalization and pharyngealization. In this study the author i.a. shows

that Tigrinya emmigrants in Sudan, when speaking the Sudanese dialect of Arabic,

often realize the Sudanese pharyngealized sounds as glottalized (ejective). The

native speakers of the dialect then usually accepted the ejective articulation of the

emphatic as a normal variant, while at other emphatics they pointed out the

auditory differences and described it as foreigners’ speech. The Tigrinya speakers

usually realized the difference in the articulation of , and , but usually did not

notice the difference between ejective t’ and pharyngealized .

The similarity between glottalization and pharyngealization is reflected also

in the situation in contemporary South Arabian languages (Mehri, Š ri, Soqotri),

where the glottalized articulation of pharyngealized sounds is perceived as a valid

variant (cf. SWIGGERS 1981, NAUMKIN & PORKHOMOVSKY 1981:9).

ṫ

ż

ṡ

ḋ

ṫ

e ḣ

31

Of course, other types of articulation can be effective, too, especially in the broader

concept of emphasis, as it is generally applied in the case of Arabic dialects, where one can

observe types of coarticulation like labialization (emphatic b% ,

) , (strong) nasalization

(emphatic ) , etc.

ṁ

ṅ

32

Cf., e.g., LESLAU 1957:325 in favour of the pharyngealization as proto-Semitic, KNUDSEN

1969 for glottalization as original. For an attempt at an alternative solution (emphasis =

uvularization) cf. DOLGOPOLSKY 1977. Naturally, a number of other studies have appeared.

33

Cf., e.g., ROMAN 1981 and BOMHARD 1988 for Proto-Semitic, DIAKONOFF 1984, 1987,

BOMHARD 1984 for Proto-Hamito-Semitic, etc.

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

17

These data clearly show the relation between pharyngealization and glottalization, but do not solve the problem which predated the other. We, however,

accept the arguments that glottalization was the original one, that have been

articulated already in MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:23-4,34 and that pharyngealization

appears as secondary from some of originally glottalized consonants, especially

glottalized t’ and k’. Then, the pharyngealized forms the core of the newly

formed series, while q, due to articulatory reasons,35 is not pharyngealized, but

shifted to the back and is not accompanied by coarticulation. Even in SIBAWAIH

(1889:302ff) q is not ranked together with other emphatics (mu b aqa - , , , ) ,

but with a broader set of mustacliya. 36

The secondary character of pharyngealization is, according to our view, supported also by the further development of pharyngealization in Arabic, especially

in its dialects. Arabic is then probably the originator and without any doubt the

propagator of pharyngealization.37

A similar approach, i.e. the concept of secondary character of pharyngealization, can be observed also in studies on other Semitic languages. In recent studies

we find clear statements that the correlation of emphatic phonemes that we know

from Arabic is of heterogeneous origin and moreover, that the pharyngealization

is secondary (cf. GARBINI 1972:141, note 1, similarly also 1984; DOLGOPOLSKY

1977, ARO 1977, ROMAN 1981, etc.). The concept of this correlation (as well as

the concept of the whole proto-Semitic phonological system) is dynamic and

pharyngealization is regarded as an innovation.

In most of the branches of the Hamito-Semitic languages, this correlation is

also represented, and only Egyptian forms an exception.38 In Chadic we find

ṫ

ż

ṡ

ḋ

ṫ

ṫ

34

"a) the Ethiopic "emphatics" are voiceless and, apart from Arabic, so the Semitic "emphatics"−almost without exception; b) the Ethiopic "emphatics" do not appear to influence the

timbre of neighbouring vowels and, again apart from Arabic, this seems to be the norm in

the Semitic languages (cf. however for certain facts in Akkadian SODEN, 1952, p. 12); c) the

phenomenon q > ’ in some Arabic dialects can only be explained by way of glottalization."

(Ethiopic "emphatics" stand for ejective consonants).

35

The backing articulation, when applied to back consonants, has a different manifestation

than when applied to dentals and alveolars. Cf. DELATTRE 1971.

36

Mustacliya = mutbaqa + q, h.

˘

37

Cf. the spread of pharyngealization in modern dialects of Arabic. The pharyngealized

consonants in Berber are usually ascribed to Arabic influence, too (APPLEGATE 1970).

˙

38

Emphatic phonemes are nevertheless reconstructed on the proto-Egyptian level, cf., e.g.,

RÖSSLER 1971 in his systematic reconstruction; CONTI 1976 reconstructs only emphatic t.

Sometimes, Egyptian grapheme for voiced affricate ğ (= d in egyptological transliteration)

is interpreted as corresponding to Semitic s.

˙

¯

˙

�18

Petr ZEMÁNEK

implosives (b’, d’, y’ - NEWMAN 1977).39 Cushitic offers a number of post-glottalized ejectives and implosives, with maximum of 11 emphatics in DOLGOPOLSKY’S (1973) reconstruction. Berber has pharyngealized consonants, cf., e.g.,

the reconstruction of K. PRASSE (1972), where we find , , and . Generally, the

pharyngealized articulation of Berber emphatics is ascribed to the influence of

Arabic.

Glottalization is thus the quantitatively prevailing type of articulation, and

according to its behaviour in loanwords, it seems that the emphatic consonants

were non-voiced (cf. DIAKONOFF 1991-92:59). The Hamito-Semitic evidence

offers also an indication of the possible development from glottalization to pharyngealization. MERLINGEN (1978) speaks of Chadic implosives b’ and d’ as

sounds characterized by "laryngealized voicing" or "creaky voice". This might

point to a certain degree of articulatorily similarity and the direction of succession

of the two ways of articulation.

The transition from glottalization to pharyngealization must have been a

process which had to leave some traces in the system. It is probable that after the

release of the glottal occlusion applied in the articulation of the glottalized consonants, the way for the participation of voice opens (postglottalized ejectives are

attested only as non-voiced), and such a possibility could result in the existence of

doublets alternating in non-voiced emphatic and its voiced counterpart. These

types of alternation were noticed already in BROCKELMANN 1908 (e.g. 160, 162

for / z), MAIZEL’ 1983, cf. also PETRÁČEK 1987, 1990:288; for "emphatic" q cf.

CANTINEAU 1960:182, CONTI 1976, ROMAN 1981 etc. According to us, in the

moment of substitution of glottalized articulation by the pharyngealized one, part

of the roots with the glottalized t’ and k’,40 and, with some reservation, possibly

also the roots with emphatic 41 change after the release of the glottal occlusion

to roots with the voiced counterpart of the originally glottalized consonants.

ż

ḋ

ṫ

ṡ

ṡ

39

JUNGRAITHMAYR & SHIMIZU 1981 reconstruct the following "emphatics" (i.e. implosives

and ejectives): b’, d’, y’, k’, s’; STOLBOVA (1986), obviously in a maximalist reconstruction,

reconstructs the emphatic series in the following way: p, t, c, č (c), k, kw, q. It should be said

that "emphatic" in the Russian concept corresponds rather to the "gepreßt" from TRUBETZKOY’S (1939) gepreßt x nicht gepreßt opposition.

˙

40

The situation at the shift from glottalized k’ to uvular q is in Arabic obscured by the fact,

that the voiced counterpart which is reconstructed in the protosystem is changed to its

palatalized variant (g > ğ).

41

The question of the original articulation is not clear, the discussion has not been concluded

and the possibility remains of original affricated articulation, which would set this consonant

somewhat apart from our speculations.

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

19

Such a type of alternation is attested also from other Semitic languages,

where e.g. in Old Babylonian graphemic representation, the signs with d are used

for words with etymological (cf. MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:31; SODEN 1952:§29,

§26b.42

For the test of our hypothesis we used the method, which is in Semitistics

relatively common, i.e. the collecting of the so-called doublets. This method is

based on the character of the root in Semitic languages (or in Arabic, to be more

precise), which is formed in the vast majority by 3 consonants that serve as basis

for the morphological derivations and that bear some "basic meaning". Doublets

then are such types of pairs of roots that differ in only one of the three radicals in

the specified position, i.e. for alternation / d an example for a doublet would be

e.g. bl / bld.

This method has been used e.g. in the discussion about the original character

of the root in Semitic, namely as the supporting argument for the biradical character of the Semitic root, as shown e.g. by the so-called PR3 series.43 For a radical

explanation of this phenomenon cf. EHRET 1989.44 Furthermore, the method is

relatively often used for showing the original character of a phoneme, cf., e.g.,

STEINER 1977 passim for doublets like ś/l, ś/ , / l, etc.

On the other hand, it has to be said that this method cannot be considered a

reliable one. It is, beside the formal differences of one element in the root, based

on semantic similarity that can be influenced very often by subjective criteria of

the researcher, and often these criteria can be hardly defined by some rules, since

the existence of doublets can be caused not only by historic relations between the

two roots, but also by the subsequent phonetic and phonological processes, phonetic similarity, etc.

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

ḋ

ḋ

42

VON SODEN 1952: §29b says: "In der Schrift werden d, t und t aA (= Altassyrisch)

nirgends, aAK (= Altakkadisch) fast nie unterschieden ...". Cf. also GELB 1961:29 and the

following discussion. These problems were obviously caused by the character of the cuneiform script which did not represent the emphatic phonemes. These were in Akkadian

substituted by signs for auditory similar sounds. Nevertheless, in Greek loanwords we find

non-voiced t for emphatic t (DIAKONOFF 1991-92:59).

˙

˙

43

Cf., e.g., MOSCATI ET AL. 1964:72-73, where there are given examples like Hebrew prd

"to separate", prm "to tear", prs "to split", prs "to break down" etc., which are interpreted as

a biconsonantal root base pr with the basic notion "to divide". For critique, cf. VOIGT 1988,

for an alternative explanation of this phenomenon, cf. PETRÁČEK 1987.

˙

44

This study is an attempt to assign certain types of meanings to the root extensions. Such

an explanation goes probably too far, when one realizes that a number of such alternations

can be caused by phonetic reasons. Another problem is that EHRET concentrates on R3 only,

while Semitic offers data on the alternation of both R1 and R2 as well.

�20

Petr ZEMÁNEK

It is exactly these types of processes, i.e. phonetic and phonological, that are

very frequent in Semitic languages and especially in Arabic. A good overview of

the richness of these processes in Semitic languages is given in MAIZEL’ 1983

which deals with the processes of the expansion of the roots in Semitic, with the

main processes allothesis, metathesis and chaining (of the type PR3 series, cf.

above).

Relatively frequent are also alternations based on clearly phonetic reasons,

e.g. the alternation of semivowels (w, y), laryngeals (c/ , h/ , c/’ etc.), alternations

like d/ / s, etc.

These facts lead us to the conclusion that the use of this method without some

accompanying correction procedures is not sufficiently valid. With the assumption

that it is difficult to avoid the subjectivity when collecting the data, we have

decided to use the method together with a control set of data that were collected in

the same way as the sets that are at the centre of our attention. The control sets that

we use are of a twofold character: the first consists of doublets, where there is a

clear phonetic relation in the alternation, i.e. doublets with alternations / t, q/k and

/ s, and the second that contains doublets of phonetically clearly non-related

sounds. For the choice of the second set clearly quantitative criteria were used. We

have chosen the consonants according to their relative frequency as given in

HERDAN 1962:54, and the resulting pairs were r/b (occurrence frequencies 7,7%

/ 5,7%) and / ġ (occurrence frequencies 1,8% / 1,9%). Such a choice offers,

despite the subjectivity of the input procedure the possibility to compare the

results of the data collection, since it offers information on relative frequencies of

the doublets. It should also allow for setting up a more contoured picture of the

situation and processes that took place in Arabic.

ḣ

ḣ

d̄

ṫ

ṡ

t̄

2.1 Analysis of the alternations of non-voiced emphatics with their voiced counterparts

2.1.1 Emphatic and its alternation with voiced d

The emphatic has the central position in our hypothesis, according to which

this phoneme represents the connecting bridge between the older type of articulation of emphasis - glottalization - and the newer type - pharyngealization.45

The doublets of / d we consider as the residue of the period when the glottalized

t’ was changing into pharyngealized . After the loss of the glottal stop a way

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

45

The other phoneme could be q, but this consonant does not fit exactly to the model of

development from glottalization to pharyngealization. Its articulation in Arabic cannot be

characterized as pharyngealized, but uvularized.

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

21

opened for the participation of voice in the articulation and part of the roots with

t’ changed into roots with voiced d, and other part changed to roots with pharyngealized , with overlapping of the two sets. It is exactly this overlapping that

documents this change. Because of reasons given above the type of articulation

that emerged at , the correlation of emphatic pharyngealized consonants is created.

Then, in the part of the doublets where the t’ changed to d, originally as an

allophone, the d received gradually phonematic character. The voiced explosive

d thus has two origins - one is the old phoneme (*d as opposed to *t etc.), and the

other is the original variant of glottalized/pharyngealized .

In the dictionary of A.B. KAZIMIRSKI (1860) we find a relatively large number of these doublets (cf. Table I):

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

Table I: Alternation of / d in Arabic

274

14,59

Total

40

37

32

109

ṫ

%

d

R3

d

212 249

18,86 14,85

ṫ

total number of

roots in the dictionary

R2

d

200 259

ṫ

ṫ

Number of doublets

R1

d

214 782

ṫ

ṫ

Alternation / d

on the position

626

18,5 12,35 14,95 13,93 17,41

Such a frequency, especially the frequency of doublets with the emphatic ,

is clearly very high. It is hard to imagine that such a frequency could be a result of

purely random similarity, although the phonetic similarity in this case plays a

considerable role.

The amount of the onomatopoetic (or, somewhat more widely, descriptive)

phonemes in the corpus is relatively low and is almost exclusively restricted to the

group of / d = R1 (R1: T’T’; Tqq; Tnn; TnTn; R2: hThT; R3: 0). Normally, these

types of roots might influence the results of the analysis, since the semantic

similarity can be caused by the character of these words, i.e. the phonetic imitation

of some sound or process. Here, in this case, considering to the very limited

number of these phonemes (less than 2% in the highest possibility), we can suppose that their occurrence will not influence the analysis.

Table II shows the phonetic distribution where the alternation / d is preserved

(only the consonants in the contact position are given; this means in the case of R2

ṫ

ṫ

ṫ

�22

Petr ZEMÁNEK

both contact positions before and after the alternation is given - the third number

is the total of the preceding two):

Table II: Phonetic environment of the alternation / d in Arabic:

a) voiced consonants:

ṫ

R1

Alternations of / d

on the position:

ṫ

consonants:

b

r

z

R2

(R3)

2

2

0

3

2

1

5

2

1

7

(∑)

7

6

0

5

3

4

9

3

3

8

Total

(R2)

2

5

1

2

1

5

2

2

2

5

12

12

1

9

6

11

13

9

10

17

ġ

l

m

n

h

w/y

(R2)

3

2

0

2

2

2

3

4

5

4

Total:

27

48

27

100

%

67,5

67,6

75,75

69,45

R3

Total

(R2)

1

2

2

1

0

1

0

1

4

2

12

7

8

3

5

5

c

(R1)

5

4

0

2

1

3

4

1

2

1

R3

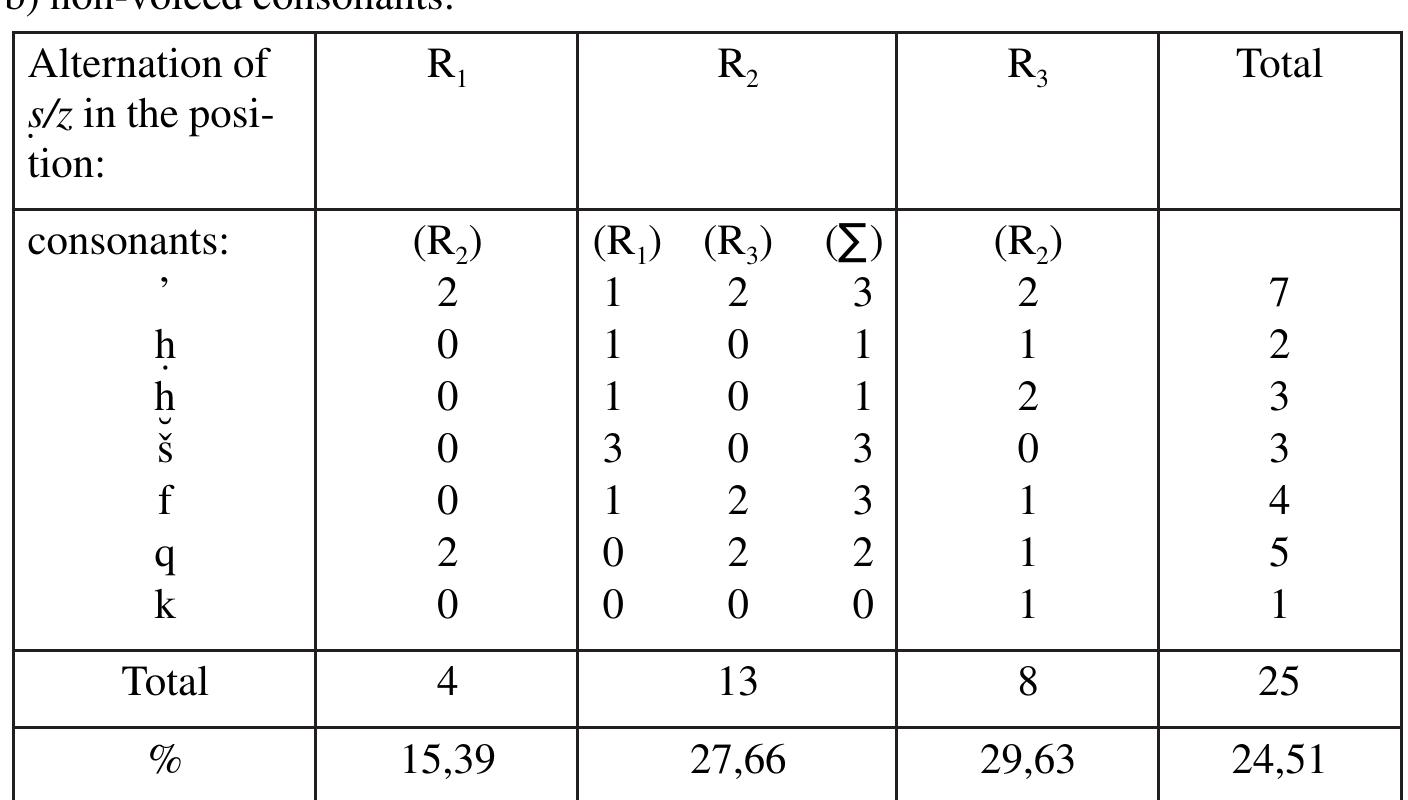

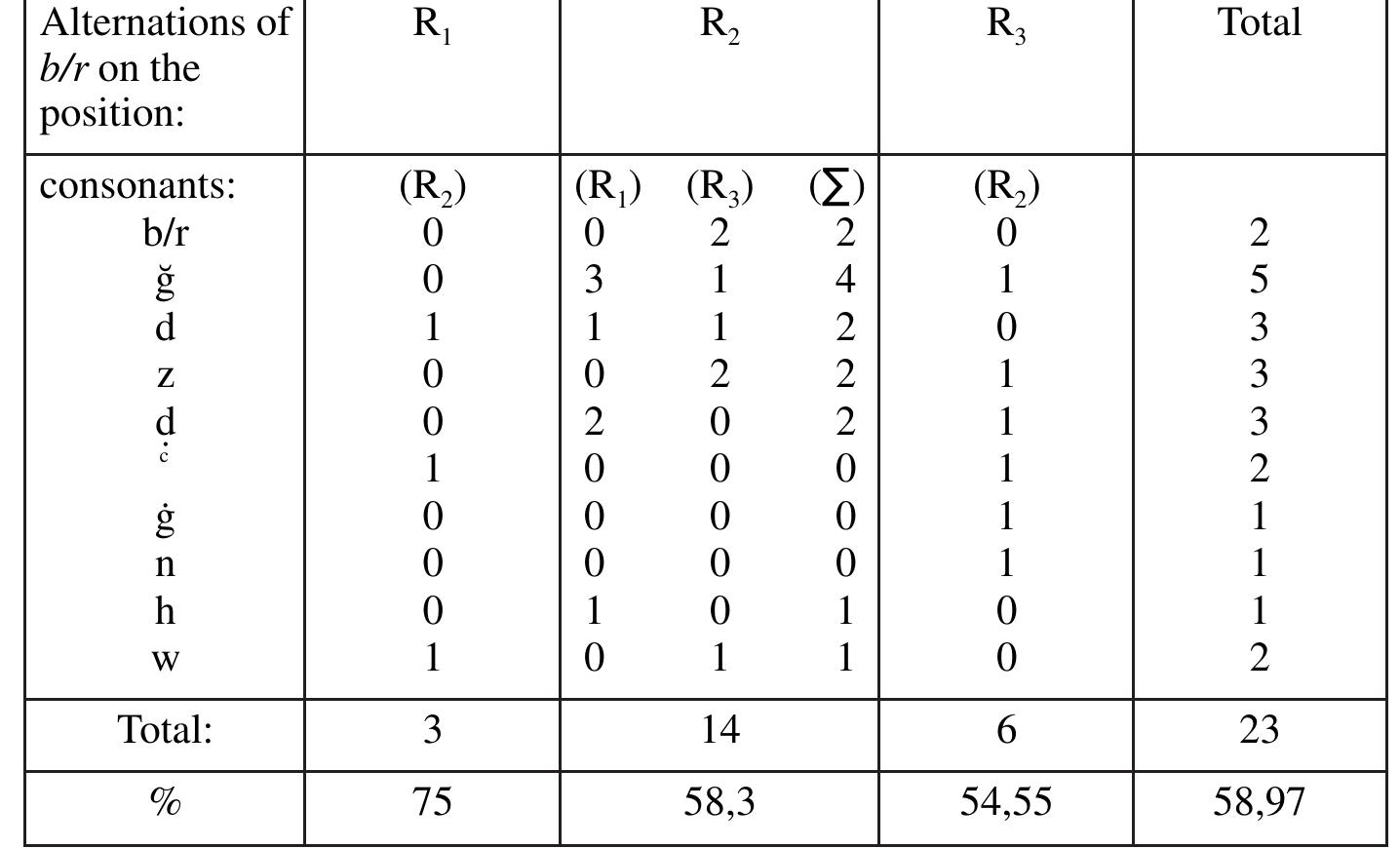

b) non-voiced consonants:

Alternation of / d

on the position:

ṫ

consonants:

’

R1

R2

h

s˘

š

f

q

(R2)

1

0

5

2

3

0

1

1

(R1)

0

0

2

3

4

2

1

3

(R3)

2

0

3

1

1

0

1

0

(∑)

2

0

5

4

5

2

2

3

Total

13

23

8

44

%

32,5

32,39

25,8

30,55

t̄

ḣ

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

23

The table clearly shows a great dominance of the voiced consonants in the

contact positions of the alternation. It is remarkable that the occurrence of the

voiced consonants is proportional, in most of the cases the number of occurrences

is about 10 (9-11). Only m and especially w/y occur more frequently. The voiced

consonants are mostly from the group of the so-called "glides" or the transitory

zone [(C) - LIQ - SON - LAR - SV - (V) - cf. K. PETRÁČEK 1971]. Only b, ġ and z

do not enter this zone.46

The group of non-voiced consonants is clearly much smaller than the group

of voiced ones. Also the distribution of these phonemes is much less proportional

than is the case at the first group. Half of them does not occur at all the subgroups

(according to the position of alternation, i.e. R1, R2 and R3). The phoneme with the

highest occurrence ( ) comes also from the group of the "glides".

It is evident that the character of the neighbouring phonemes played a substantial role in preservation of (and, possibly, to a certain degree in the causing)

the alternation of / d, and served also as the catalyst of the transition. It is probably

the voicedness that helped in the preservation of this alternation, and moreover, in

the contact position, there are consonants from the zone of the transition between

consonants and vowels (cf. PETRÁČEK 1971), that exhibit a high degree of voicedness (liquids, sonants, semivowels).47

A certain number of doublets in this set are interrelated phonetically. Namely,

they are the following: at R1: 17. Tcs - 18. Tcz, 29. Tnn - 30. TnTn; at R 2: 31. mTT 33. mTw/y; at R3: 2. blT - 24. lbT, 10. zrT - 11. zlT. The alternations in these roots

(beside the alternation of / d) can be explained by phonetical changes.

Morphologically most of the doublets preserve the alternation in its verbal

manifestation; nominal patterns are rather rare.

Semantic analysis could also show some interesting facts. That is why we

tried to divide the doublets into groups that are evident in the data. The present

analysis is based only on our own division, and is to be considered tentative.

Although the semantic division here is rather speculative, we consider it

useful to mention it here, since it can bring interesting facts to the environment

where the alternation is preserved. This holds also for the semantic division of the

doublets with the alternation of q/ğ and / z.

The Table III shows the semantic division of the doublets with the alternation

of / d:

ḣ

ṫ

ṫ

ṡ

ṫ

46

According to RŮŽIČKA in a number of studies (e.g., 1954) and PETRÁČEK 1955, 1975, it is

possible to count ġ among the glides due to a supposed transition of c > ġ.

47

For the question of the degree of sonority, cf. GVOZDANOVIĆ 1985:89.

�24

Petr ZEMÁNEK

Table III: Semantic division of the doublets with / d in Arabic.

R1

violence, aggressivity

ṫ

Alternation of / d on the position:

R2

R3

Total

4

13

9

26

actions connected with movement

10

6

7

23

actions and activities connected with

space

2

3

4

9

spiritual and corporal qualities

10

4

3

17

taboo actions and activities

2

4

3

9

production of sounds

5

1

0

6

rest

7

6

6

19

40

37

32

109

ṫ

Total

It is evident that most of the features that we have managed to distinguish in

the data are somehow connected with some emotional charge (aggressivity,

violence, etc.), spiritual and corporal qualities (mostly pejorative) or with dynamics (movement, etc.). These three groups form almost 60% of the whole. Emotional charge can without doubt be seen also in the taboo actions and activities (8

doublets).

Thus, with 53 doublets we can speak of emotional charge, with 23 doublets

of dynamics (especially movement; a certain dynamics could be also ascribed to

some of the doublets that are here gathered under the "rest" label). This dynamics

can be to a high degree strengthened by the fact that most of the doublets are

verbs.

We assume that it is also this dynamic and emotional charge in the semantics

of the doublets that plays its role in preserving the remnants of the transition of t’

> / d > , d.

Nevertheless, in our tentative semantic analysis we did not find any regular

semantic change due to the variant used. That is why we consider this alternation

as caused mainly by phonetic features, mostly by the voiced environment of the

alternation.

ṫ

ṫ

2.1.2 Uvular q and its alternation with voiced ğ:

As has been said above when describing the uvular q, this phoneme can

hardly be associated with the other "emphatic" phonemes of Arabic, both from the

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

25

phonetic and phonematic point of view. This phoneme enters our analysis only on

historical grounds.

There are many reasons why we should consider this phoneme as originally

glottalized, one of them is the alternation with the glottal stop ’ in a number of

Arabic dialects (e.g. in Egypt and elsewhere). Here, we would like to add another

argument.

Based on the hypothesis formulated above, we suppose also with this phoneme the transition k’ > q, i.e. a change in the manner of articulation. After the

release of the glottal closure, there is a way opened for the participation of voice,

and thus for the transition k’ > g. In Arabic, this transition is somewhat obscured

by the fact that the original g was palatalized to ğ (we assume this transition

according to the correspondences among the Semitic languages without examining

the reasons for this process). In spite of this, as our data show, the traces of the

transition k’ > q in Arabic are preserved in a number of doublets.

In the dictionary of A.B. KAZIMIRSKI (1860) we find the following number of

doublets of q/ğ:

Table IV: Alternation of q/ğ in Arabic:

Alternation q/ğ

on the position

R1

R2

R3

Total

Number of doublets

50

21

36

107

total number of roots ğ

in the dictionary

357

%

q

ğ

413 205

14,00 12,1 9,46

q ğ

q ğ

248 322

363 884

q

1024

8,43 11,18 9,91 12,10 10,45

As opposed to the alternation of / d, the relative (i.e. percentual) number of

the doublets with the alternation of q/ğ is smaller. We suppose that this relatively

smaller number of doublets is caused by the related palatalization g > ğ, which

without doubt influenced the possibility of the preservation of the traces of the

change.

As onomatopoeic (or descriptive), the following roots can be determined:

Qšš, Q Q, šQQ, and hQhQ. Their number is so small that even here we can

exclude any considerable influence of these words on our analysis.

The following table gives the phonetic environment of the alternation of q/ğ,

summarizing the consonants in all the contact positions of the alternation:

ṫ

ṡ

�26

Petr ZEMÁNEK

Table V: Phonetic environment of the alternation of q/ğ in Arabic:

a) voiced consonants:

Alternations of

R1

R2

R3

q/ğ in the position:

consonants:

b

d

l

m

n

h

w/y

(R2)

2

4

3

9

0

2

5

4

3

2

2

Total:

36

36

28

90

%

72,00

69,23

84,85

72,00

R2

R3

Total

(R2)

0

0

2

0

1

0

2

-

1

3

5

5

5

1

12

3

d̄

r

z

c

(R1)

0

1

0

1

0

1

0

1

1

4

3

(R3)

1

0

0

2

0

3

2

2

1

1

1

(∑)

1

1

0

3

0

4

2

3

2

5

4

Total

(R2)

5

2

0

2

1

2

6

2

1

3

4

8

7

4

14

1

8

13

9

6

10

10

b) non-voiced consonants:

Alternation of

q/ğ in the position:

consonants:

’

R1

f

0

(R2)

1

2

1

4

1

0

5

-

Total

14

16

5

35

%

28,00

30,77

15,15

28,00

t̄

ḣ

s

š

(R1)

0

1

2

1

3

1

2

-

(R3)

0

0

0

0

0

0

3

3

(∑)

0

1

2

1

3

1

5

3

ṡ

�Pharyngealization and Glottalization

27

Just as with the preceding group of doublets ( / d) the phonetic environment

of the alternation is formed mostly by the voiced consonants. Most frequent are

liquids and semivowels, the role of laryngeals, esp. h, is also substantial. Into the

group with higher occurrence come the sounds r, l, h, w/y (with occurrence over

10), while at the other extreme stands z with one occurrence only.

ṫ

Non-voiced consonants in the environment of the alternation are much less

frequent than voiced ones. It is interesting that here the phoneme f is very prominent. It occurs more than twice as often as the other most frequent phonemes ( ,

s, š). On the other hand, in the case of this alternation, the occurrence of one

"emphatic" phoneme ( ) is also attested here.48

ḣ

ṡ

In this group also occur roots of the type R1R2R2 which are here under the

non-voiced consonants where the third consonant is labelled with 0 in the table.

It is interesting that with the preceding group this type of root was of very low

occurrence.

Again it is possible to say that it is the voiced environment, especially

sounds with high degree of voicedness that are close to vowels (liquids, semivowels, laryngeals) which served as the catalyst for the transition and also where

most traces of the transition are attested.

As it has been the case at the / d alternation, here also we can find some doublets whose interrelations can be explained by phonetic reasons. Namely they are

the following: at the alternation on the position of R1: 7. Qdd - 11. Q ; 19. Qrf 37. Qlf; 30. Qff - 32. QfQf; at the position of R3: 6. b Q - 7. hbQ; 10. drQ - 12.

˘

rdQ; 28. frQ - 29. flQ.

ṫ

d̄

d̄

ḣ

Morphologically also the verbs are dominant and nominal (mostly adjectival) meanings are not so frequent.

The tentative semantic analysis is given in the following table.

48

Root sQQ; it is especially the combination of these two consonants that is very common

in Arabic.

˙

�28

Petr ZEMÁNEK

Table VI: Semantic division of the doublets of q/ğ in Arabic:

Alternation of q/ğ in the position:

R1

R2

R3

Total

violence, aggressivity

16

9

8

33

actions connected with movement

2

3

6

11

actions and activities connected

with space

0

2

2

4

spiritual and corporal qualities

7

2

5

14

taboo actions and activities

0

1

4

5

production of sounds

0

1

2

3

dryness

4

0

0

4

"draw in, remove"

9

0

0

9

rest

12

3

9

24

50

21

36

107

total

The table shows, as was the case of the semantic analysis of the alternation of

d/ , the dominance of meanings of emotional charge and dynamics (violence,

taboo actions and spiritual and corporal qualities - 52 doublets, movement - 20

doublets).

Unlike the alternation / d, however, the meanings in the individual groups of

doublets (i.e. R1, R2 and R3) are not distributed so proportionally. Here we have