At any given moment, scientists say, there should be at least one interstellar object—perhaps a castaway asteroid or comet from another star—passing through the inner solar system. In 2017 astronomers discovered the first such interloper known as it flashed past our planet at high speed. Dubbed ‘Oumuamua, this mysterious object is now outbound from our solar system, already too far away for further telescopic scrutiny and traveling too fast for any current spacecraft to ever catch up. Chances are, we will never see it again. But as quickly as ‘Oumuamua came and went, experts began to wonder if we might manage to visit any future interstellar visitor we discover.

Now a new European mission may do just that. Called Comet Interceptor, the mission was selected on June 19 by the European Space Agency to either visit an interstellar object or a distant comet making its first journey into the inner solar system. Designed with no particular target in mind, the planned spacecraft is instead meant to be a sentinel in space, awaiting a rendezvous opportunity. “We’ve selected a mission where we don’t know where we’re going for the very first time,” says Nicolas Thomas of the University of Bern in Switzerland, who is part of the Comet Interceptor team.

ESA officials project it will cost approximately €150 million, or $170 million, to ready Comet Interceptor for a planned 2028 launch as a secondary payload to the agency’s Atmospheric Remote-sensing Infrared Exoplanet Large-survey (ARIEL) space telescope. ARIEL will be bound for a position some 1.5 million kilometers from Earth, well beyond the moon, known as Lagrange point 2 (L2). L2 is a special region of stability where the gravitational influences of Earth and the moon almost cancel out, allowing a spacecraft to linger there while expending minimal fuel.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Alongside ARIEL, Comet Interceptor will also travel to L2, where it will wait for astronomers to spot a worthy target. Mission controllers will then signal the spacecraft to fire its thrusters and chase down its quarry for closer examination. The spacecraft will not land on its destination, instead conducting a fast flyby and observing its target for only a matter of minutes from a distance of perhaps 1,000 kilometers. But Comet Interceptor will also have two smaller dronelike spacecraft that will be sent closer to the object to gather more detailed data without risking damage to the main vehicle.

While the spacecraft waits at L2, the mission’s science team will actively search for potential visitation targets, looking in particular for a comet inbound from the depths of the outer solar system. So far, all previous spacecraft-comet rendezvous—such as the Giotto and Vega missions to Halley’s Comet in 1986 or Rosetta’s trip to Comet 67P/Churyumov-Gerasimenko in 2014—have involved short-period comets, which regularly swing past the sun and thus have changed considerably since forming in the early solar system more than four billion years ago. “They’ve been heated many times,” says Geraint Jones of University College London, the lead of the Comet Interceptor mission. “With the heating, you change the nature of the surface.”

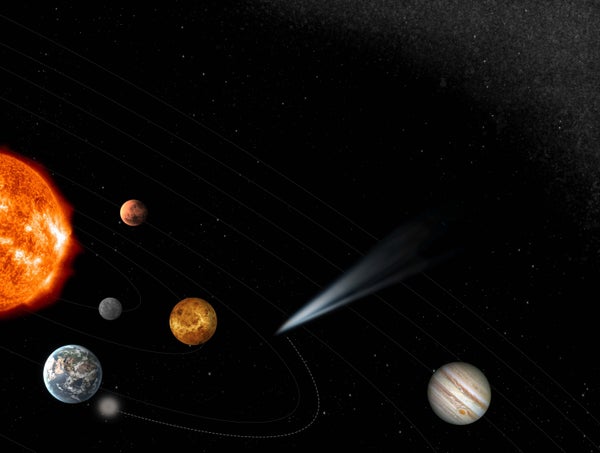

Studies of a more pristine, so-called long-period comet on its first foray toward the sun could offer fresh insights into exactly how our solar system arose all those eons ago. Comet Interceptor will carry instruments capable of discerning such a comet’s ingredients, vintage and appellation—when and where it was made and from what. Most long-period comets are thought to have formed somewhere in the realm of our solar system’s planets before they were scattered farther out by Jupiter and other newborn giant worlds. There, those primordial outcasts formed what is known as the Oort cloud, a vast region of comets that envelops the solar system and extends out to a light-year or more.

The other top priority target for Comet Interceptor (and it can only visit one object) would be an ‘Oumuamua-like interstellar object. Because no suitable spacecraft was at the ready when ‘Oumuamua flew by in 2017, astronomers had no choice but to watch it rapidly fade in their telescopes as it sped away. They plan to be better prepared next time.

“That excitement, that idea that you could get to a genuinely interstellar object from another solar system, helped promote the case for this particular mission,” says Mark McCaughrean, the ESA’s senior adviser for science and exploration. “We believe it’s possible if you find another interstellar object, of which there should be lots.”

Finding long-period comets, not to mention interstellar objects, remains rather tricky—for now, anyway. ‘Oumuamua was first spied by the Panoramic Survey Telescope and Rapid Response System (Pan-STARRS), which has a wide-angle eye on the sky, but Pan-STARRS’s panoramic view will soon be dwarfed by another upcoming observatory. That observatory—the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST)—is planned to begin operations on a mountaintop in Chile in 2022. “We expect to find on the order of 10,000 comets over the full 10-year survey,” says Meredith Rawls of the University of Washington, who is part of the LSST team. “And we’ll observe each of them 50 times, so we’ll get a lot of different images.”

Along the way, astronomers should also discover a number of interstellar interlopers, although no one is yet sure of exactly how many. LSST, its planners say, could spot ones of sufficient size (at least a few hundred meters wide) out past the orbit of Saturn, years before they make their closest approach to the sun. Such early warnings would give the Comet Interceptor mission plenty of time to plot a course for one of these objects, providing it crosses the plane of Earth’s orbit when it enters the inner solar system.

Present plans call for the spacecraft to wait at L2 for up to three years before it must depart for a target. If no long-period comet or interstellar object is seen in that time—which is about a one-in-four chance, according to the team—Comet Interceptor would simply visit a “plan B” destination. One potential back-up target would be the short-period comet 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann 3, which is thought to be a fragmented comet.

In a best-case scenario, Comet Interceptor will have a variety of targets to choose from—an embarrassment of riches that would force the team to make some tricky decisions. Should it gamble and wait for a high-value target, such as an interstellar object, or leave L2 at the first opportunity even if the target is less exciting? These discussions will take place over the next few years, but the possibility of going to an interstellar object could be quite alluring. “I feel like it would be a no-brainer,” says Darryl Seligman of Yale University, who has studied potential trajectories and operations for such an encounter. “But you don’t know if ‘Oumuamua was a one-off or not.”